California Pension Liabilities Raise Debt Uncertainty

The California Public Policy Center (CPPC) issued a report Wednesday to assess the state's current debt obligations. The authors include William Fletcher, a retired senior vice president at Rockwell International (an industrial manufacturing conglomerate), and Ed Ring, CPPC's research director and the editor of Union Watch.

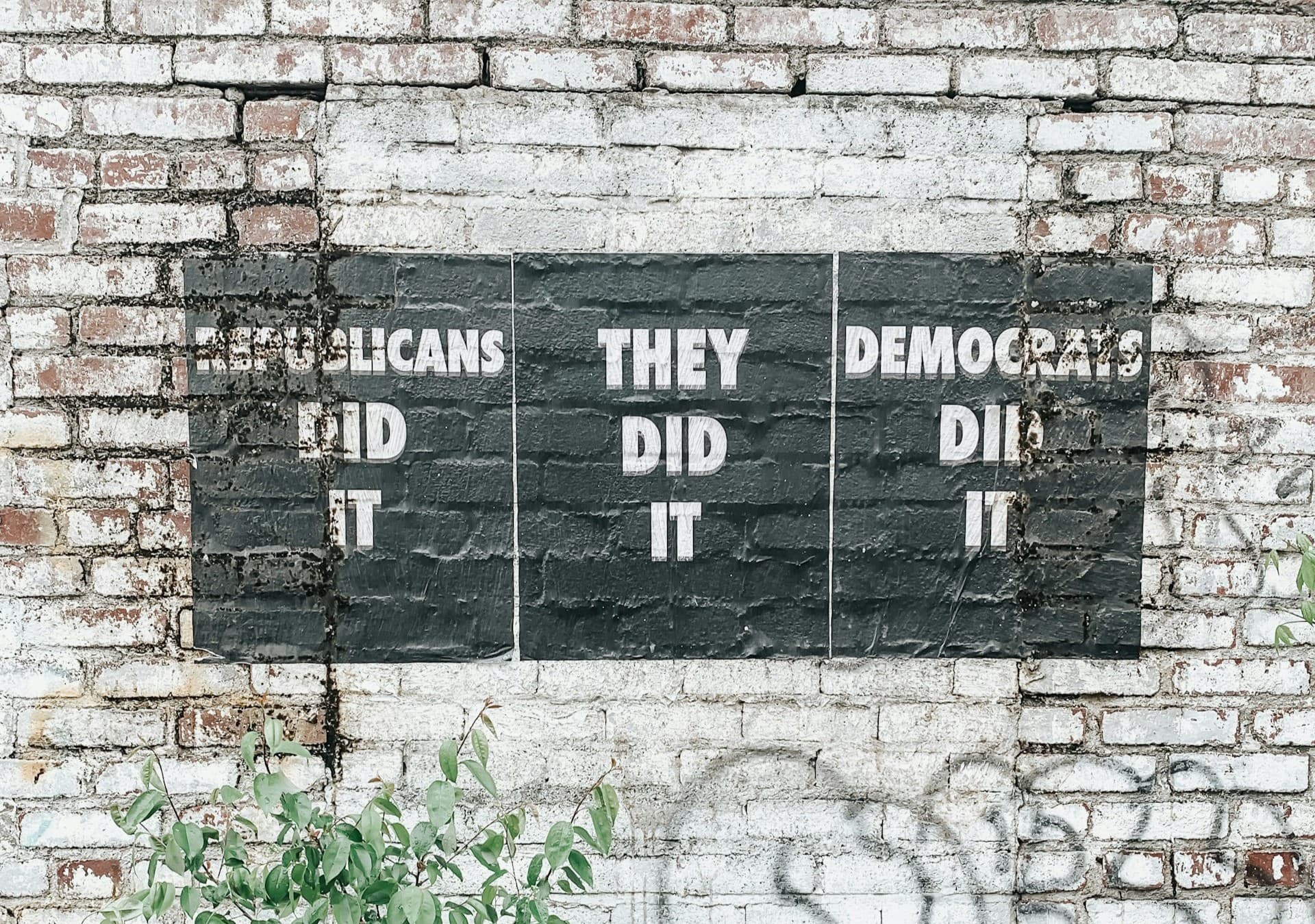

Taking an accurate snapshot of California's fiscal situation is a difficult and often politicized task. Consequently, the report has not been immune from similar criticisms.

Nevertheless, it's no secret that California has a debt problem. As one of the most indebted states in the nation, California has a reputation for unbalanced budgets and spending tomorrow's revenues today.

credit: CPPC

The report examined multiple sectors of government spending, including the 'wall of debt' (coined by Governor Jerry Brown), unemployment insurance, and various obligation and revenue bonds. When these factors are added up, the state government's debt is an estimated $132.6 billion.

Additional analysis shows California's K-12 public schools hold about $49.7 billion in bond debt, city governments hold $68.1 billion, and county governments hold $22.1 billion. When taken together along with California's other state and local government entities, debts reached over $850 billion. Following additional adjustments, which accounted for more conservative growth, outstanding debt reached into the trillions.

The culprit cited by CPPC is the state's ballooning pension liabilities. The key lynchpin here being the estimated investment return rate. Historically, an average annual return of 7.5 percent would be considered appropriate, yet a much more conservative rate of 5.5 percent or lower is considered by CPPC to be much more accurate.

The authors argue in the report:

"The economic landscape that generated an historic 7.5% average rate of return for these funds has been seismically altered. Interest rates are at historically low levels because of actions by the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks. This reduces pension fund interest income near-term and could lead to losses on bond portfolios when interest rates eventually return to normal."

It's evident that pension liabilities do lie at the crux of California's budget difficulties even if taken at the 7.5 percent return rate, yet a much more dire fiscal outlook is inevitable if economic growth doesn't reflect historical trends.

The question that remains unanswered by CPPC, however, is what solution to the California pension question would take into account the fact that such retirement benefits are indeed 'obligations' to the state's teachers, police officers, and other government employees. Is rationing retirement benefits promised to workers the only solution?

As the first report of its kind, CPPC invited other policy experts to analyze their data to compile an even more accurate picture of California's mounting debt. Perhaps if other policy groups step forward to tackle the debt problem, California will be able to reverse perceptions of poor budgetary stewardship.