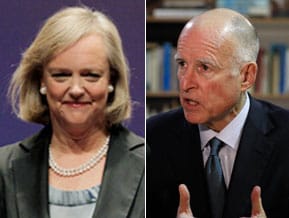

Whitman and Brown offer distinct campaign strengths and weaknesses

Republican gubernatorial candidate Meg Whitman, having weathered a primary against one of the more dogmatic opponents in recent years, appears to be headed for either a landslide victory or a landslide defeat, with little margin for error in between.

On the one hand, her opponent, former Governor and current Attorney General Jerry Brown, enjoys a natural political advantage with California’s electorate, and is running in a recession, making Whitman’s business credentials potentially dangerous, if spun as anti-populist. On the other hand, Brown’s campaign is strapped for cash, whereas Whitman is rolling in both political and financial capital, and has begun outreach to voters on the opposite side almost instantaneously.

Brown, who remains the favorite in polling data, has an approach more naturally suited to the political environment currently appearing in California. Having just passed Proposition 14 and eschewed most of the bills sponsored by divisive interests, Californians seem hungry for a consensus politician, an approach which Brown has offered almost too well.

According to the Long Beach Press-Telegram, Brown “promises that if elected, he will instantly sit down with everyone involved in the state decision-making process, from legislators to public employee unions.” This extremely deferential approach, while historically short on results, will give Brown the ability to claim that all voices will be welcome under his adminstration, in contrast with the fiscally tough-minded Whitman, whose credentials as CEO (not to mention her political messaging) speak of a political and economic worldview utterly devoted to efficiency, at the expense of political warm feelings.

On the fiscal side, Whitman also retains a substantial money advantage. According to the Los Angeles Times, many California Democrats are having second thoughts about Brown because:

“Republican gubernatorial nominee Meg Whitman barely paused to take a breath after her landslide primary victory, saturating the airwaves with ads, raising money across the state, trying to woo traditionally Democratic voters and using her massive campaign machine to drive the conversation in her race against rival Jerry Brown."

Brown, meanwhile, is off the air, has yet to reach out to strategic voter blocs, and has drawn more attention for his gaffes than actual policy proposals.

If Whitman's strategy pays off, her name recognition should skyrocket, allowing her natural financial advantage to control the debate, and thus giving her more of a chance to shape the pre-election narrative. Given the extraordinarily anti-incumbent and anti-establishmentarian impulses percolating around the country these days, such control could end badly for Brown.

At the same time, it’s not clear that it will seal the deal for Whitman. Consider, for instance, her recent ad on Jerry Brown’s “legacy of failure.” While the ad is no doubt potentially effective, its claims are, according to the nonpartisan website FactCheck.org, not entirely accurate.

According to a summary by the website, “The ad claims that "crime soared" while Brown was mayor of Oakland. That's false. The total number of crimes actually went down by more than 13 percent." Also false is the ad's claim that Brown "damaged the school system so badly the state had to take it over." As mayor, Brown had almost no control over the school district, which was run instead by an elected school board.

A charge that Brown "lobbies for a corporate polluter" is highly misleading. Brown wasn't a paid lobbyist. The claim is based on a phone call he made for a past campaign contributor, and it had nothing to do with pollution. The ad claims Brown worked to "send California jobs to China," but that's unproven. The claim rests on an 18-year-old newspaper story that Brown strongly denied.

Some of the ad's other claims lack context. For example, it's true as claimed that California had unemployment of 11 percent when Brown finished his time as the state's governor. But the ad fails to mention that the national unemployment rate was 10.8 percent at the time, when Ronald Reagan was President.

While it is worth noting that Fact checks of attack ads have a poor track record of convincing voters, the multiple charges here will permit Brown to rebut any attack ad Whitman points out as potentially slanderous. Whatever anti-incumbent sentiments exist in the electorate today would thus be blunted, by virtue of the uncertainty about Whitman’s trustworthiness.

Whitman’s campaign thus faces a formidable challenge as far as media relations go, even if it can successfully control the narrative using its abundant war chest. As the saying goes, "with great power comes great responsibility."