Health Care Behind Bars - How It Really Works

The health care crisis behind bars affects two distinct but deeply connected groups: incarcerated individuals and correctional officers.

While incarcerated people are constitutionally entitled to care, access remains inconsistent, and most enter custody with significant medical and mental health needs. They face higher rates of chronic illness, infectious disease, and psychiatric conditions than the general public.

Often forgotten in the discussion are the people tasked with overseeing the prison population: correctional officers.

Correctional officers, by contrast, have no guaranteed right to care. Yet they work in high-stress environments that put them at elevated risk for PTSD, suicide, and long-term physical illness. A 2024 Health & Justice review said correctional officers have “seriously compromised physical, mental, and social health and measurable rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that approach or exceed that of military combat veterans.”

Why?

This episode of How it REALLY Works examines how a system built for punishment is expected to serve as a hospital, crisis center, and workplace, and what that means for the people living and working behind prison walls.

The Hidden Prisoner Health Crisis Behind Bars

Do Prisoners Have a Right to Health Care, and Is That Health Care Good Enough?

The United States Constitution does not explicitly guarantee a right to health care, but incarcerated individuals are afforded limited protections under the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. In the landmark 1976 case Estelle v. Gamble, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “deliberate indifference to serious medical needs” of incarcerated people constitutes a constitutional violation. Justice Thurgood Marshall, writing for the majority, concluded that denying necessary care amounted to the “unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain.”

This ruling established a constitutional floor for medical treatment in prisons and jails, but that floor is low. In the years since Estelle, courts have interpreted the “deliberate indifference” and “serious medical need” standards narrowly. Facilities are not required to provide optimal care or even care that meets contemporary clinical standards. They are only obligated to ensure that inmates are not intentionally ignored or denied treatment for urgent and recognized medical issues.

Legal scholars and advocates have pointed to the gap between this legal threshold and what most Americans would consider adequate care. As long as there is no “conscious disregard,” even negligent or outdated care may pass constitutional muster.

Why ‘Basic Care’ Is Often the Best Prisoners Can Get

- The Eighth Amendment standard applies only once a person has been convicted and incarcerated.

- Courts have ruled that delays in care, incorrect diagnoses, or limited treatment do not violate the Constitution unless intent can be proven.

- The burden of proof lies with the individual, who must show that prison officials knowingly disregarded a substantial risk to their health.

- Medical decisions, even if poor, are protected unless they reflect a total lack of professional judgment (Farmer v. Brennan).

This gap between legal rights and medical realities was brought into sharp relief in California in the early 2000s. On April 5, 2001, nine men incarcerated in California filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court, alleging that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was failing to meet even basic health care standards. The federal court ultimately agreed. In 2005, a judge declared the state’s prison health care system “broken beyond repair” and appointed a federal receiver to take over its management. The case, originally filed as Plata v. Schwarzenegger, is now known as Plata v. Newsom.

Since the receivership began in 2006, California has invested billions into reforming its prison health infrastructure. However, the legacy of Estelle and Plata remains: a legal right to health care in prison is only as strong as the systems and oversight put in place to enforce it.

How Sick Is the Prison Population?

Prisons and jails across the United States have become de facto health care providers for some of the nation’s sickest populations. Decades of research have confirmed that incarcerated individuals suffer disproportionately from chronic illness, infectious disease, mental health disorders, and untreated substance use. Many people enter custody already in poor health due to a lack of access to care in the community, poverty, trauma, or housing instability.

In the prison setting, health care systems must triage care based on “acuity,” a clinical term that refers to the urgency and complexity of a patient’s health needs. In California, where medical conditions are now centrally tracked by the California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS), the volume of high-need patients is staggering.

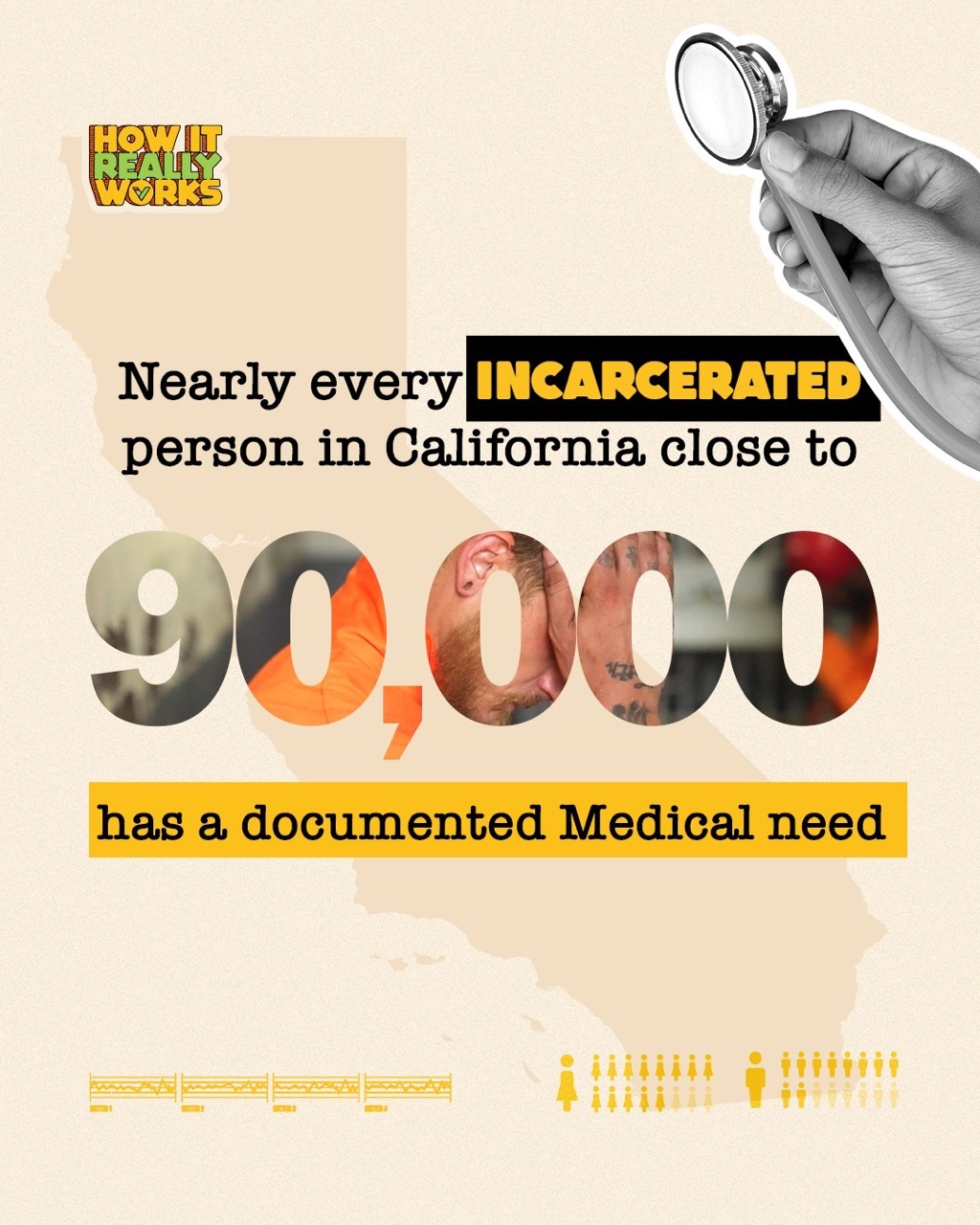

By the Numbers: California’s Prison Health Landscape

- 18,124 individuals were classified as high medical acuity, meaning they require intensive treatment or daily medical oversight.

- 35,092 individuals had medium acuity needs, often requiring regular chronic care visits, psychiatric management, or close observation.

- 37,608 individuals were designated low acuity, indicating stable conditions that still require access to basic health services.

- 90,744 total incarcerated patients with documented medical needs.

These figures illustrate that nearly every person in California state prison custody has an identified health condition that must be managed, often within a system historically unequipped to provide timely or comprehensive care.

National studies reinforce this picture. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 40% of state and federal prisoners nationwide have been diagnosed with a chronic condition like hypertension, diabetes, asthma, or arthritis. Nearly two-thirds report symptoms of a mental health disorder. Rates of hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and HIV are all significantly higher than in the general public.

What Can We Learn from California’s Prison Health Experiment?

Since being placed under federal receivership in 2006, California's prison health care system has undergone significant reforms aimed at addressing longstanding deficiencies. The appointment of Receiver J. Clark Kelso followed a federal court's determination in Plata v. Newsom that the state was failing to provide constitutionally adequate medical care to incarcerated individuals. Over the past two decades, Kelso's office has implemented numerous initiatives to improve health care delivery within the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. A 2023 audit by the Office of the Inspector General revealed that incarcerated individuals with chronic illnesses often faced delays of weeks or months for follow-up care, underscoring ongoing staffing shortages and systemic inefficiencies.

Nevertheless, progress is evident. As of March 2025, oversight of medical programs at 29 of the state's 33 prisons has been delegated back to the CDCR, indicating substantial improvements in health care delivery. Receiver Kelso emphasized this achievement, stating:

The goal of the receivership has always been to build a health care system that is efficient, well-managed, self-monitoring, and sustainable... This is a true testament to the significant improvements you have all made creating a safer, more effective health care environment for incarcerated people.

While the receivership has facilitated notable enhancements in California’s prison health care system, continued efforts are necessary to address remaining gaps and ensure consistent, high-quality care for all incarcerated individuals.

Who Pays for Prison Health Care, and What Does It Cost?

Once a person enters jail or prison, they lose access to most forms of public health insurance, including Medicaid and Medicare. This policy, known as the “inmate exclusion," has been in place since 1965. It prohibits federal Medicaid funds from being used for medical services provided inside correctional facilities.

The only exception is for off-site care: if an incarcerated individual is hospitalized outside the facility for more than 24 hours and is eligible and enrolled in Medicaid, coverage may apply. Otherwise, the full cost of providing medical care inside prisons falls to the state.

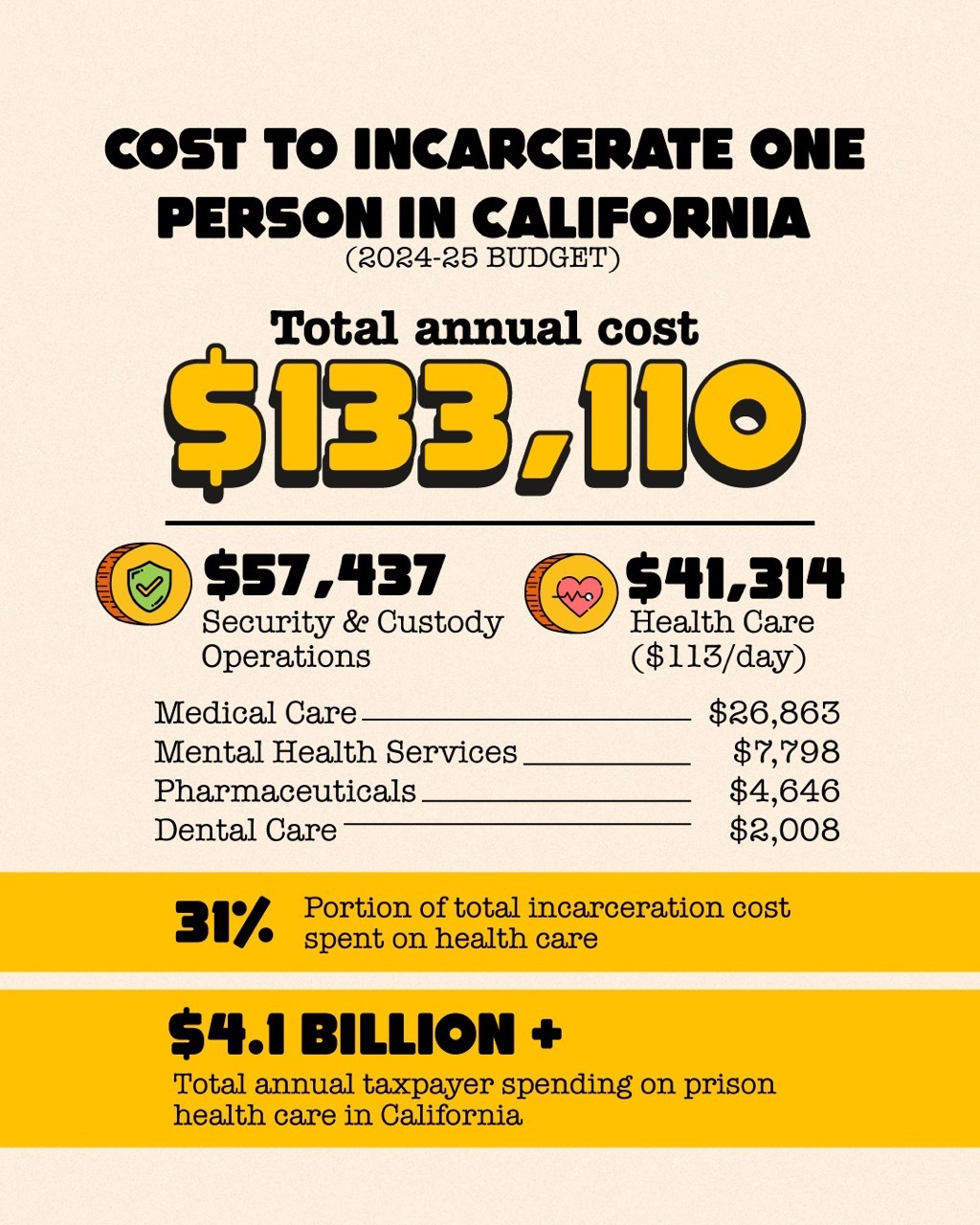

In California, the financial burden is significant. Health care costs now account for nearly one-third of the total cost of incarceration—and those costs continue to climb.

What Incarceration Really Costs in California

According to the 2024–25 Enacted Budget, the average annual cost to incarcerate one person in California is $133,110. Here's how that breaks down:

These costs have more than doubled in the past two decades, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. Oversight and delivery of this care is managed by California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS), which operates across all 31 CDCR institutions.

Signs of Change: Medicaid Reform and Reentry Support

In April 2023, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a major policy update allowing states to apply for Medicaid waivers that cover certain health services in the 90 days before release from incarceration. California became one of the first states to receive such a waiver.

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, California’s demonstration project includes:

- A pre-release care plan including screenings, medication management, and coordination with outside providers

- A 30-day supply of medications upon release, helping bridge the treatment gap during reentry.

- Public health and behavioral health follow-up once individuals return to the community.

In December 2023, Congress passed legislation requiring state Medicaid programs to cover certain health services for incarcerated youth, effective January 2025. These developments mark a notable shift in federal correctional health policy, with a growing emphasis on reentry planning and continuity of care.

What To Do About Transgender Prisoners?

In 2017, California adopted a first-in-the-nation policy allowing gender-affirming health care, including surgery, for incarcerated people. The state approved of surgery for a transgender woman serving a life sentence, and she was later transferred to a women’s prison. In 2021, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law requiring that everyone be asked gender-specific questions upon entering prison to determine whether they should be housed in a men’s or women’s facility.

As of late 2023, more than 20 incarcerated individuals had undergone gender-affirming surgeries through the state system, according to CalMatters. However, this number dropped from 99 surgeries the previous year, reflecting funding constraints and shifting policy priorities.

Nationally, access remains inconsistent. A California Law Review article outlines how conflicting interpretations of the Eighth Amendment and emerging state laws have led to a patchwork of legal protections, leaving many transgender incarcerated individuals without necessary care.

Transgender Care and Custody: Conflicting State and Federal Law

- In 2017, California became the first state to explicitly allow incarcerated individuals to access gender-affirming surgeries, including for those serving life sentences.

- In 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom signed SB 132, requiring that all people entering California prisons be asked about their gender identity and housing preferences during intake. Facilities must comply unless they document specific safety concerns.

- As of December 2022, more than 20 incarcerated individuals had received gender-affirming surgeries through California’s system, and more than 100 surgeries had been approved. (CalMatters report).

- Access to gender-affirming care in prisons remains highly inconsistent across the United States, varying widely by state and facility.

- A California Law Review analysis warns that conflicting state laws and interpretations of the Eighth Amendment have created a patchwork of legal standards and protections.

- In 2025, President Trump issued an executive order mandating that transgender women be housed in men’s prisons and that federal prisons stop providing gender-affirming treatments, a move directly at odds with California law. Trump’s “gender ideology” order said the attorney general “shall ensure that males are not detained in women’s prisons or housed in women’s detention centers” and that no federal funds go to gender-affirming treatment or procedures for people in custody.

How the conflict between the federal and state approaches will be resolved is yet to be determined. In the meantime, those who are charged with administering the prison system will be caught in the middle of this nationalized ping pong match.

Why Are So Many Officers and Legislators Visiting Norway's Prisons?

Norway’s prison system operates on a fundamentally different philosophy: that incarceration should focus on rehabilitation, not punishment. Facilities are designed to mirror life on the outside, with private rooms, kitchens, and shared living spaces. Officers are trained in communication and conflict de-escalation, often acting more like social workers than guards. Most importantly, these innovative approaches have been shown not only to reduce recidivism significantly, but they also promote safer correctional environments.

In 2017, a group of U.S. correctional officers and prison administrators visited Norwegian facilities as part of a reform initiative. As reported by Corrections1, the delegation observed that staff-prisoner relationships were grounded in mutual respect, and incarcerated individuals retained significant autonomy over their daily lives.

In 2023, the Texas Public Policy Foundation led an international prison tour to Germany and Norway as part of its Right on Crime initiative. The delegation included U.S. legislators, corrections officials, prosecutors, nonprofit leaders, and law enforcement representatives. Their goal: to study prison systems that emphasize rehabilitation, dignity, and reintegration.

In Germany, incarceration is treated not as an extended punishment but as a temporary loss of liberty, with daily life designed to mirror the outside world. Officers are trained to support, not just guard, inmates, and facilities invest heavily in education, mental health care, and reentry planning. Participants observed that Germany’s approach produces lower recidivism and better public safety outcomes than many U.S. models.

The full report from the Texas Public Policy Foundation recommends applying key principles from the European model to U.S. justice systems, such as trauma-informed supervision, family engagement, and consistent reentry services, to improve outcomes and reduce incarceration rates.

Norway’s Prison Model, in a Nutshell: What U.S. Leaders Are Learning

- Rehabilitation First: Norway’s system views incarceration as the loss of liberty, not dignity. Prisons focus on preparing individuals to reenter society, rather than punishing them further behind bars.

- Designed for Humanity: Facilities include private rooms, shared kitchens, and open spaces, designed to mirror life on the outside and reduce institutionalization.

- Staff as Mentors, Not Guards: Correctional officers are trained in communication, mental health awareness, and conflict resolution. Their role centers on support, not control.

- Global Interest Grows: In 2017, U.S. correctional officers and prison leaders visited Norway to observe this model. In 2023, a broader delegation, including legislators and prosecutors, toured German and Norwegian prisons with the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

- Better Outcomes, Lower Recidivism: Delegates noted stronger relationships between staff and incarcerated people, lower violence, and improved reentry success rates.

- California Adapts the Model: Through the California Model, CDCR has begun implementing key principles like dynamic security, normalization, peer support, and trauma-informed care, starting with a pilot at San Quentin.

California has begun to translate some of these international insights into its own system through what it calls the California Model. Piloted at San Quentin and expanding across the state, the initiative is a system-wide strategy led by the CDCR and CCHCS to integrate both national and international best practices into the daily life of state prisons. The model emphasizes dignity, safety, and structured rehabilitation, not just for those serving time, but for the people charged with supervising them.

Applying the Lessons: California’s Early Application of the Norway Model

- Infrastructure Development: California has authorized approximately $1.5 billion, primarily through lease-revenue bonds, to fund the construction and renovation of 31 health care facilities across the prison system. As of early 2025, 22 of these projects have been completed, with the remainder expected to be finalized within the year, according to the 58th Tri-Annual Report from the Receiver's Office.

- Establishment of CHCF: In 2013, the state opened the California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton, a $900 million institution designed to provide specialized care for up to 3,000 incarcerated individuals with complex medical and mental health needs.

- Pharmaceutical Reforms: To address issues with medication management, the Receiver implemented a centralized pharmacy system and standardized drug formulary. Despite these improvements, per-person pharmaceutical spending has more than tripled, from approximately $1,300 in 2004–05 to $4,646 by 2024–25.

- Staffing Enhancements: Recognizing critical staffing shortages, particularly among registered nurses, the Receiver increased compensation levels by 5% to 64% to attract and retain qualified medical personnel.

According to the Receiver’s most recent report, the California Model is grounded in four core pillars: dynamic security, normalization, peer support, and trauma-informed care. These principles aim to reduce violence, support mental and emotional stability, and prepare incarcerated individuals for a successful return to the community.

But just as important, they represent an overdue recognition that safer, healthier prisons depend on the well-being of everyone who lives and works inside them.

Inside the Job: The Hidden Health Toll on Correctional Officers

While public attention and research often focus on the health care rights of incarcerated people, the health of those who work in prisons, specifically correctional officers, receives far less attention. Yet correctional officers live much of their professional lives behind bars as well, immersed in a high-stress, high-risk environment that affects both body and mind.

Recent research shows that these officers are experiencing a deepening health crisis: one defined by trauma exposure, physical decline, and institutional neglect.

Multiple studies now describe correctional officers as among the most physically and mentally distressed members of the justice system workforce. And while wellness initiatives exist in some departments, officers often lack the trust or resources to access them.

This combination of risk and inaction has made correctional officer wellness a growing concern for employee safety, operational stability, and long-term public safety.

The Circumstances Correctional Officers Live With

Throughout their careers, correctional officers are exposed to a wide range of potentially traumatic experiences, including but not limited to:

- Violence or aggression from incarcerated individuals

- Life-threatening injuries

- Biohazard exposures

- Threats to self or family

- Being taken hostage

- Feeling in danger or fearful of making a life-threatening mistake

- Suicide attempts of incarcerated individuals or coworkers

- Deaths of incarcerated individuals or coworkers

The Impact of the Job on Health and Wellbeing

-

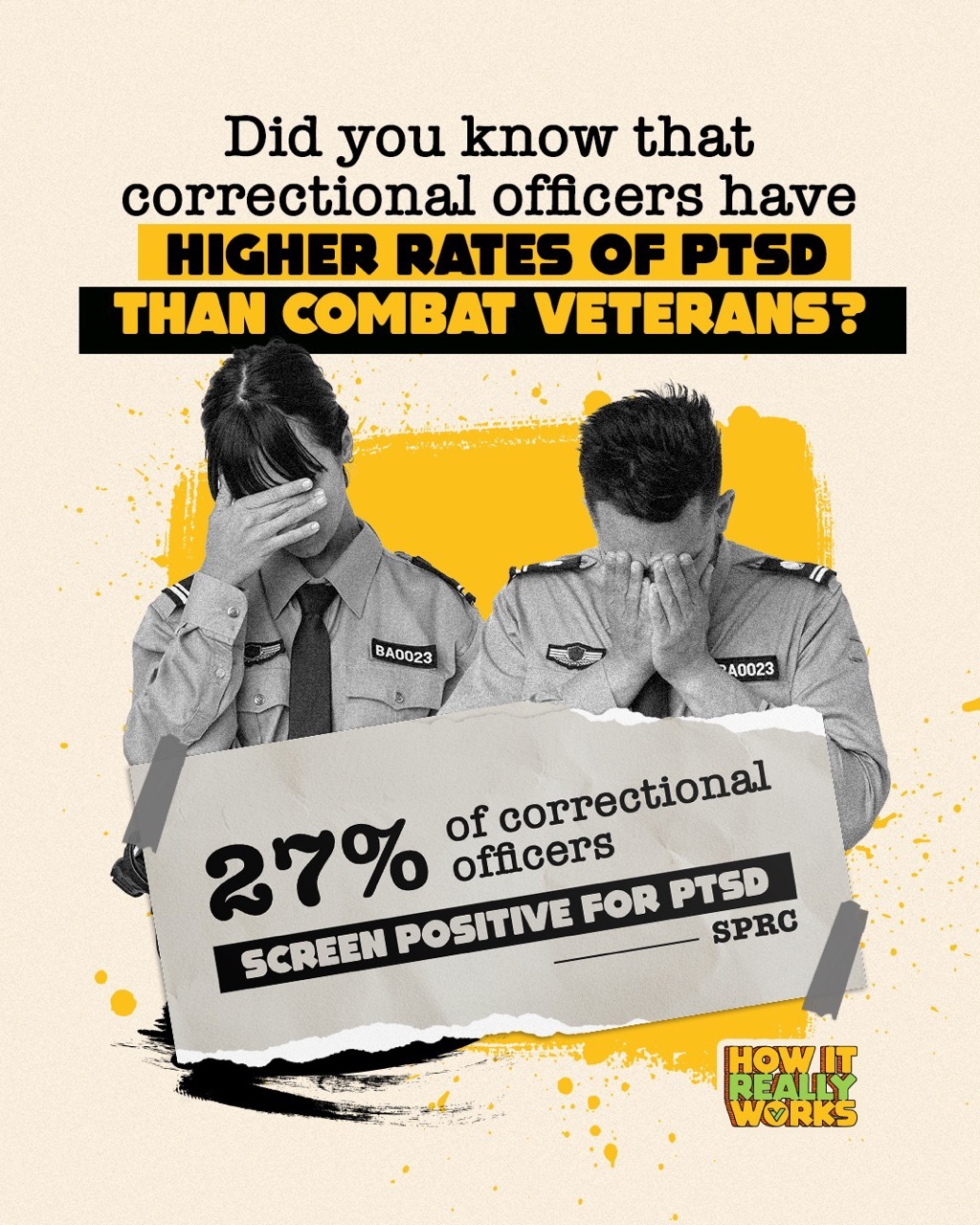

Correctional officers have higher rates of PTSD than any other law enforcement group, with some jurisdictions reporting rates over 29% (Health & Justice, 2024).

- Officers have measurable rates of PTSD that approach or exceed those of military combat veterans.

- Suicide is more common among correctional staff than death by inmate assault (SPRC).

- Officers experience elevated levels of hypertension, sleep disorders, obesity, and chronic pain due to long hours, rotating shifts, and stress-related inflammation (FHE Health).

- According to the Vera Institute, the isolating and reactive nature of prison environments contributes to emotional withdrawal and burnout, both of which spill over into home life.

Understanding the health care needs of correctional officers is essential to any meaningful conversation about prison reform. These are the professionals responsible for administering justice day to day, and their health has a direct impact on institutional safety, staff retention, and the outcomes of the incarcerated people in their care.

PTSD, Depression, and Suicide: A Workforce in Crisis

Correctional officers face a uniquely intense form of occupational stress. Daily exposure to trauma, high-stakes environments, and institutional rigidity takes a serious toll on mental health, and too often, officers are left to manage these effects on their own. While law enforcement as a whole grapples with burnout and PTSD, corrections professionals consistently report higher rates of psychological distress than any other group in the justice system.

The Numbers Behind the Crisis

- 27% of correctional officers screened positive for PTSD (SPRC)

- 10% reported suicidal thoughts in the past year

- Officers are twice as likely to die by suicide as by inmate assault (SPRC)

- Up to 29% of officers in some jurisdictions meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Health & Justice, 2024)

- Correctional officers report significantly higher rates of depression, sleep disorders, hypertension, and substance misuse than the general population.

In many facilities, mental health resources are minimal or inaccessible.

Even more confounding is that the culture of corrections, marked by stoicism, hypervigilance, and fear of retaliation, discourages officers from seeking support. Policies around mental fitness evaluations often create fear that acknowledging mental distress could jeopardize careers.

The stress doesn’t stay at work. The Vera Institute notes that emotional detachment and burnout spill into home life, fueling family strain and long-term health risks. The California State Auditor’s 2018 report also raised red flags about post-incident care, highlighting that after traumatic assaults like “gassing,” many officers receive little or no mental health follow-up.

Researchers and policymakers alike are calling for systemic reform: confidential mental health services, peer support programs, trauma-informed supervision, and routine wellness checks. Without these changes, the health of correctional staff and the sustainability of the system itself remain in serious jeopardy.

Support Systems in Name Only? Why Mental Health Services Often Go Unused

While many corrections departments promote wellness programs on paper, the reality is that few officers feel safe or supported enough to use them. Fear of being labeled unfit for duty, lack of trust in confidentiality, and institutional stigma continue to prevent officers from accessing the help they need.

Warning Signs from the Frontlines:

- Nearly 50% of correctional officers report experiencing mental health symptoms, but most never seek formal care (Mental Health First Aid).

- Over 40% report clinical depression, and 30% admit to problematic drinking or substance use (FHE Health).

- 63% say their department offers no routine psychological evaluation or wellness training (One Voice United).

- Correctional officers have some of the highest rates of addiction in law enforcement, yet also report low engagement with treatment services (American Addiction Centers).

Even where Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) or peer support are available, uptake remains low. The culture of corrections often discourages emotional vulnerability, and many officers fear retribution or sidelining if they disclose personal struggles.

Some progress is emerging. CDCR has expanded wellness resources and offers confidential access to mental health professionals, while national groups like One Voice United are building trauma-informed training and PTSD screening programs for correctional staff. Officer testimonials, such as those featured in this video spotlight, continue to push the conversation forward.

Federal policymakers are now stepping in. A bipartisan 2025 bill proposes establishing national wellness standards for correctional staff, including mandated wellness check-ins, protected access to care, and increased funding for on-site clinical services. Advocates say the solution isn’t simply more programs — it’s making them credible, accessible, and free of fear.

Beyond Pay: Turnover, Culture, and the Crisis of Retention

Correctional officers often earn salaries that appear competitive on paper, but the realities of the job — chronic stress, mandatory overtime, and limited autonomy — paint a more complicated picture. According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, entry-level correctional officers in California earn approximately $59,000 per year, with experienced officers earning more than $100,000 when factoring in overtime and seniority. However, real earnings vary depending on post location, shift schedules, and staffing shortages.

The 2024 CalHR Unit 6 Salary Survey found that California officers earn approximately 28% more than their peers in other state systems; however, they also experience significantly higher mandatory overtime and burnout rates. Meanwhile, a Benchmark Analytics report warns that financial incentives alone are not enough to address what they call a “wellness crisis” in corrections.

Nationally, data compiled by All Criminal Justice Schools shows average correctional officer salaries at around $53,000, with federal officers earning slightly more. But according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, even federal facilities are struggling to attract and retain staff, citing emotional strain, family disruptions, and dangerous work environments as core challenges.

A recent JED Platform article highlighted that while pay remains a critical factor in recruitment, it is poor workplace climate and insufficient wellness infrastructure that drive many officers to leave. A national survey cited in the NIJ reports that over 50% of correctional staff would not recommend the profession to others, echoing findings from earlier research in California.

When Paychecks Can’t Fix the Compensation Problem

- $59,136–$113,000: salary range for California correctional officers (CDCR)

- 28% higher compensation in California compared to other U.S. states (CalHR, 2024)

- 53% of surveyed officers nationwide say they would not recommend the job (NIJ)

- High turnover and vacancy rates are reported across local, state, and federal systems

Reform advocates argue that competitive pay must be matched with investments in wellness, agency culture, and long-term retention strategies. Suggestions include reducing forced overtime, expanding trauma support services, and fostering leadership pathways that value emotional intelligence, not just time served. Without meaningful cultural change, even high-paying departments may struggle to maintain a healthy, stable workforce.

A System Built for Punishment Needs Care

Incarcerated individuals have a constitutional right to medical care, but the reality behind bars is inconsistent and often inadequate. Across the country, prison health systems operate under fragmented oversight, thin budgets, and a growing reliance on private contractors. As a result, the quality and timeliness of care vary widely, sometimes from one cellblock to the next.

At the same time, correctional officers are confronting a parallel health crisis. With some of the highest rates of PTSD, suicide, and chronic disease among public safety professions, many officers work in environments that degrade their mental and physical health. Support systems exist, but they are fragmented, stigmatized, or underused.

What emerges is a system designed for punishment now being asked to function as a hospital, a mental health facility, a rehab clinic, and, of course, a healthy workplace. Yet few of these roles were built into its foundation. The health and sustainability of the correctional system, both for those inside and those who guard the gates, will depend not just on funding or facilities, but on whether the system can evolve to recognize and meet the complex human needs it now holds.

Cara Brown McCormick

Cara Brown McCormick