California’s Governor Race Is a Democratic Nightmare, But There’s One Easy Fix

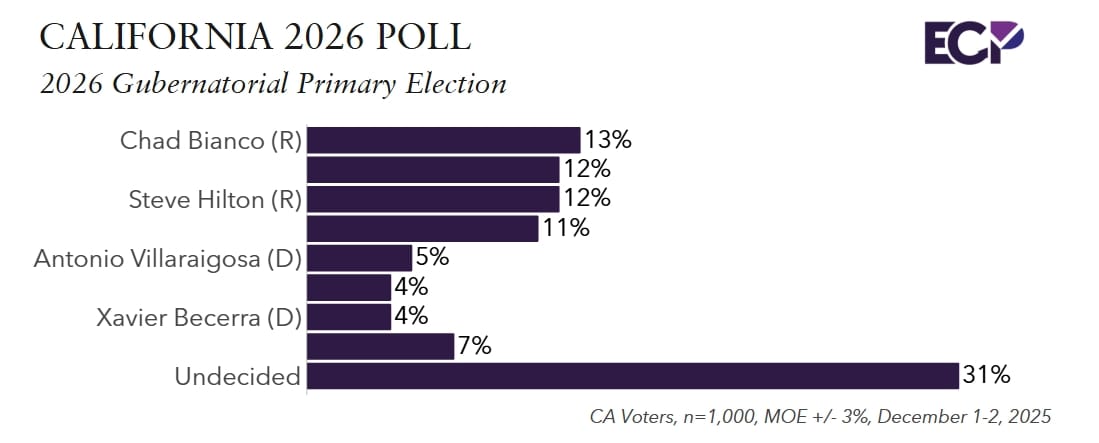

A new Emerson College poll of California’s 2026 governor’s race confirms what many election observers have suspected. California is entering a high stakes primary season with no clear front runners, a crowded field, and an election system where the outcome often depends less on voter preference and more on mathematical luck.

And before anyone rushes to blame the nonpartisan primary, it is worth remembering that closed primaries produce even fewer Democratic outcomes. Closed primaries exclude independent voters, reduce participation, empower hardened partisans, and guarantee that November voters are stuck choosing between nominees they never had a meaningful chance to support.

California’s nonpartisan system was designed to improve on that. The problem with the top-two system, particularly with a large field, is that the math breaks down in ways voters rarely see.

But 2026 might expose the need for a fix.

Under California’s rules, who advances to November is often determined not by who voters like the most, but based on who else happens to file and get into the competition. Yes, candidates must raise money and build coalitions. But once enough candidates enter the race, the decisive variable becomes something they can’t control: each other.

A random Republican “John Smith,” for example, is almost guaranteed to advance if no other Republican runs. But add one more GOP contender, even a weaker one, and the vote splits in ways that could knock both out. On the Democratic side, the dynamic becomes even stranger.

If dozens of Democrats file, mainstream candidates divide the majority vote across many similar choices, while a fringe candidate with a small but concentrated base can jump into the top tier simply because their voters don’t split.

This isn’t voter driven competition, its math. And it could create a Democratic nightmare.

Scenario One: Two Republicans Advance in a Deep-Blue State

If several Democratic candidates split their own coalition into small slices while one or two Republicans consolidate theirs, a blue state can easily end up with two Republicans on the November ballot. It has happened before under California’s rules and can happen again, especially when large fields dilute competitive lanes.

Scenario Two: Democrats Advance That Most Democrats Didn’t Support

Even if Republicans fail to place a candidate in the top two, Democratic voters could still be stuck with nominees who only captured a small fraction of primary support. In a crowded field, it’s entirely possible for finalists to advance with backing from well under 20 percent of voters. That leaves the broader electorate with choices they never made and never endorsed.

Scenario Three: A Celebrity Candidate Breaks the System

California has a long track record of elevating celebrity figures into political contention practically overnight. Under a top two system, a recognizable outsider only needs 15 to 20 percent of the vote to outpace a field of experienced candidates who divide the remaining support among themselves. We’ve seen this dynamic in California. We’ve seen it nationally. A system built on plurality advancement practically invites it.

The Pattern Is Familiar, and Other States Have Responded

California is not the only state that has run into these structural failures. Alaska moved to a top four system, giving voters a broader and more representative general election field. Local efforts such as More Choice San Diego are pushing for a top five structure, and early polling shows support hovering around 70 percent.

Voters understand the core principle: broader choice in November leads to stronger legitimacy and better outcomes.

Independent Voter Project has been advocating this reform for years, alongside a national coalition of nonpartisan organizations committed to giving independent minded voters a meaningful voice in elections.

And the data we gather from statewide engagement confirms something consistent: when voters are given more options, they participate more, pay more attention, and feel better represented by the process.

Here’s the Easy Fix: Advance 5 Candidates to the General

California doesn’t have to overhaul its entire election system. It simply has to finish the job it started when it adopted the nonpartisan primary. Instead of advancing two candidates to November, advance five.

A top five general election and let voters rank them:

- Prevents two Republicans from advancing in a blue state.

- Prevents Democrats from being stuck with nominees they never supported.

- Prevents a celebrity from hijacking the ballot with a fractured primary plurality.

- Gives November voters a field that actually reflects their preferences.

- Aligns California with modern nonpartisan reform models already succeeding elsewhere.

- Retains the virtue of Top Two because no one gets elected in November without a majority of voter support.

California’s current system forces too many voters to choose between too few options they never selected. Expanding the November ballot to five finalists gives voters what the system was supposed to deliver in the first place: more choice, more legitimacy, and outcomes that reflect the will of the full electorate.

The nightmare scenarios are all possible. The fix is simple. And California already has the blueprint to get it done.

Chad Peace

Chad Peace