California’s “Fair Pay” for Incarcerated Firefighters Hides Some Uncomfortable Math

California is calling it a milestone for fairness, dignity, and labor rights. When Governor Gavin Newsom signed a package of bills last week raising pay for incarcerated firefighters, the announcement made headlines across the state and drew praise as a historic step toward justice reform.

Assembly Bill 247 raises the hourly wage for incarcerated firefighters to $7.25 while they are actively fighting fires, bringing their pay in line with the federal minimum wage. Assembly Bill 799 adds a $50,000 death benefit for the families of incarcerated firefighters who die in the line of duty.

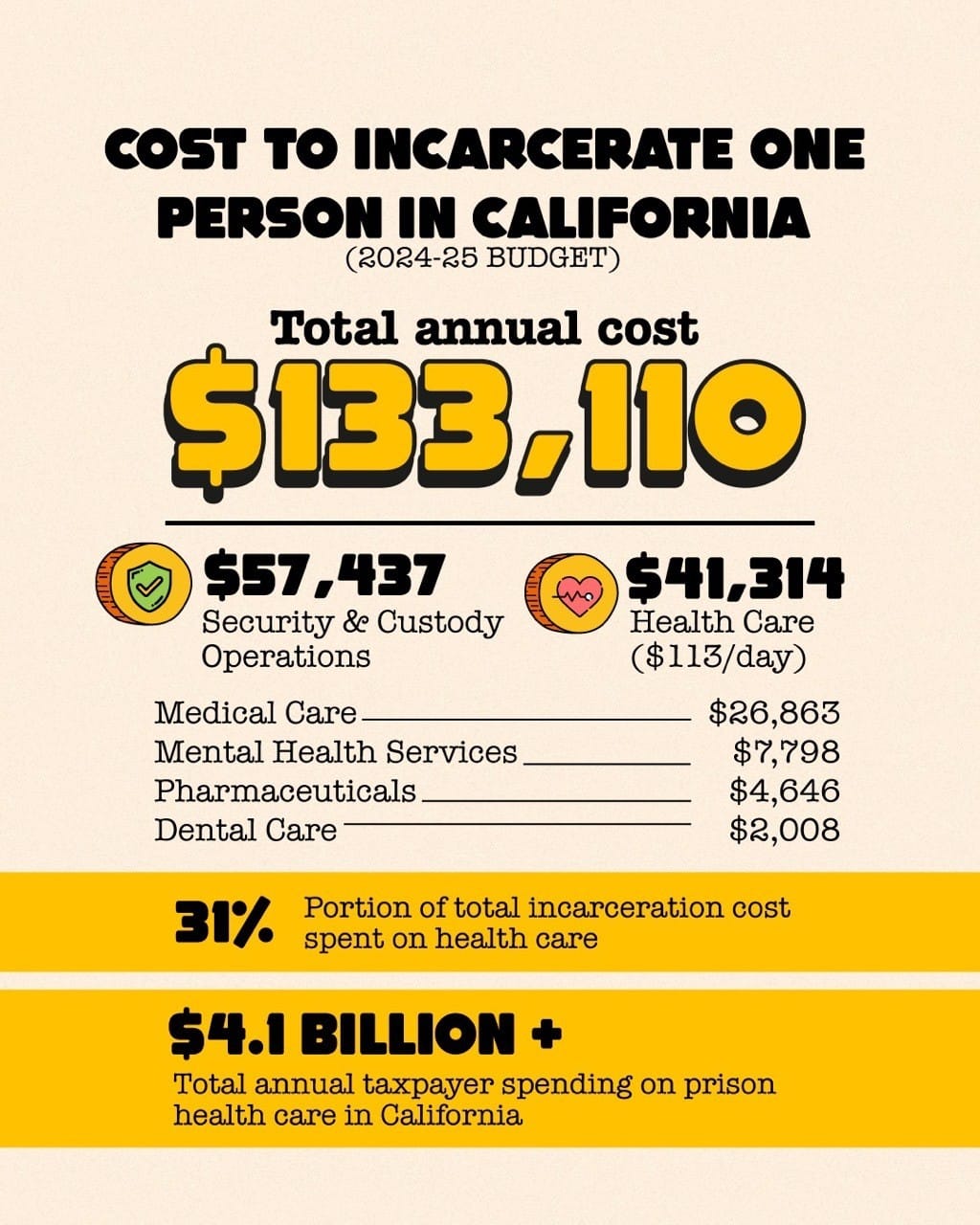

But behind the headline moment lies an uncomfortable calculation. According to California’s 2024-2025 enacted budget, it costs $133,110 per year to incarcerate one person in the state. That figure includes $57,437 for security and custody operations, $41,314 for healthcare, and thousands more for food, transportation, training, and daily supervision. Medical care alone costs $26,863 annually per person, with mental health services adding another $7,800 and pharmaceuticals about $4,600.

When all of these costs are added together, the total taxpayer cost per incarcerated firefighter can exceed what California spends on the professional firefighters and correctional officers who guard, train, or work beside them. If you convert that $133,110 per incarcerated person into an hourly rate, it equals roughly $64 an hour. Now, with the new legislation, incarcerated firefighters' hourly cost is closer to $72 an hour.

By comparison, a Chula Vista Firefighter II earns about $62 an hour when all benefits are included. According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) pay-and-benefits sheet, the hourly salary for a Correctional Officer after completing the academy works out to about $54/hour, before overtime.

On paper, both professions look stable and well compensated. In reality, California’s high cost of living quickly erodes those paychecks. The state’s cost of living is about 50 percent higher than the national average, and housing costs are more than double.

The United Ways of California recently released the Real Cost Measure 2025, designed to show the true cost of living in California. The study says a family of four in San Diego County needs $116,000 just to make ends meet.

For a Chula Vista household with two working adults and two children, the math is daunting. Living wage estimates from MIT for San Diego County show that food costs about $13,212 a year, or roughly $1,100 a month. Housing adds another $34,717, transportation about $17,982, and medical expenses approximately $9,394. Childcare, one of the heaviest financial burdens, averages $29,183 annually. Add to that $8,938 for civic and community expenses, $2,061 for internet and mobile service, and $11,490 for other essentials, and the total comes to about $126,977 after taxes, or nearly $149,000 before taxes, just to meet basic living standards in San Diego County.

Those who fight fires or guard prisons for a living must pay for all of it, including food, housing, healthcare, childcare, and transportation, out of their own paychecks. Incarcerated firefighters, meanwhile, have their living expenses, including health care, covered by the state. So, the $7.25 wage should be considered within that context.

And that is the quiet contradiction hiding behind the governor’s announcement. The raise is meant to signal fairness and dignity, but it also exposes how deeply the state already invests in those behind bars and how it compares to the people who risk their lives to keep them and the rest of California safe.

Cara Brown McCormick

Cara Brown McCormick