CA Officials Worry Further Prison Reduction Will Create Huge Problems for Public Safety

Recently, prisons nationwide have seen an increase in numbers as states get tough on crime and criminals get tough on recovery. In California particularly, the state prisons have been stuffed solid with sky-high rates of recidivism as the Legislature's slow cogs of response grind onward.

Today, the realignment fight between federal standards and realistic goals goes on, and yet re-offending, or recidivism, remains an issue. For those unfamiliar with the statistics, here is a chronology of California's "tough on crime" era.

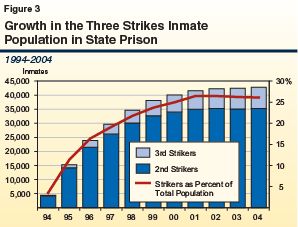

In 1994, California voters approved a major change to sentencing known as "Three Strikes," exponentially increasing sentences for inmates with repeat offenses. The purpose of the law was to discourage recidivism, either directly through punishment or indirectly through example.

While striker population has ballooned, numbers in recent years have leveled slightly as second strikers are paroled.However, by 2006, Governor Schwarzenegger was forced to declare a state of emergency in the Californian system due to overcrowding, citing "population increases, parole policies, sentencing laws, and recidivism rates" as causes. Twenty-nine out of 33 state prisons were "severely overcrowded," with immediate problems such as overloaded electrical systems and sewers, and already marginalized rehabilitative programs.

Thousands of prisoners were transported to private facilities out of state.

To release the pressure after the Three Strikes bottleneck, the California Legislature enacted an "historic" realignment in 2011, in which low-level inmates were diverted to county jails.

Once again, recidivist behavior came into target, but the necessary incentives for real impact did not come. A year after the realignment revolution, the California ACLU critiqued it as a common misuse of funds and a lack of reform or research.

Program money was rerouted to jail expansion by counties chasing outdated incentives.

"Modest sentencing reforms" for low-level offenders -- reforms critical to the realignment policy package -- were attempted and blocked in 2012. Despite the centrality of evidence in "evidence-based policy," Governor Brown has, "in name of county flexibility and autonomy," refused to mandate data collection.

Nine months have passed since the report released, concluding with four tasks for the Legislature:

- Sentencing measures to limit maximum penalties for low-level offenses

- Pretrial detention reform for low-risk inmates

- A mandate for data research

- Revisions in fund allocation for regenerative programs concerning addiction, mental health, and chronic unemployment

Shortly after the report, voters in November approved continued funding for realignment programs, but without revisions. Roughly 5 months ago, the state of emergency was rescinded and Brown has since claimed significant progress.

Indeed, since realignment was implemented, the state's 33 prisons have reduced their population from 148,000 to 123,000. However, California is expected to come up 9,636 inmates over the cap of a 2009 federal order that California reduce its population to 137.5 percent of capacity (about 110,000 inmates) by December 31, 2013. The state was at about 150 percent capacity by the end of 2012.

Brown reluctantly submitted a plan to comply with the order in May that would still fall 2,300 short, along with a recently rejected request to stay the previously upheld order. Given the looming deadline, Brown may find himself held in contempt of the U.S. Supreme Court.

According to Corrections Secretary Jeffrey Beard, however, the state can't squeeze out any more without "creating huge problems" for the safety of the public. The judges have ordered the conditional early release of more "low-risk" inmates, but Beard argues it's easier said than done.

"`Low risk' does not mean `no risk,'" he warned.

As options dwindle, the 'low risk' label will encompass more dangerous types.

Where will California find room for change in the numbers when the reality they represent is a no less brutal and insular criminal culture? How much of the state's publicly-supported damage control is productive, and how much is just a numbers game? Could political popularity draw judges toward punitive incarceration while leaving the wardens scrambling to relieve pressure two years down the line?

Shuffling inmates between out-of-state contractors and expanding the criteria for release without simultaneously loosening sentencing ensures a destructive, self-perpetuating machine that both incarcerates and releases prematurely. As the experts debate, recidivism remains an underworld tradition.