New Georgia Charter School Amendment Faces Challenges

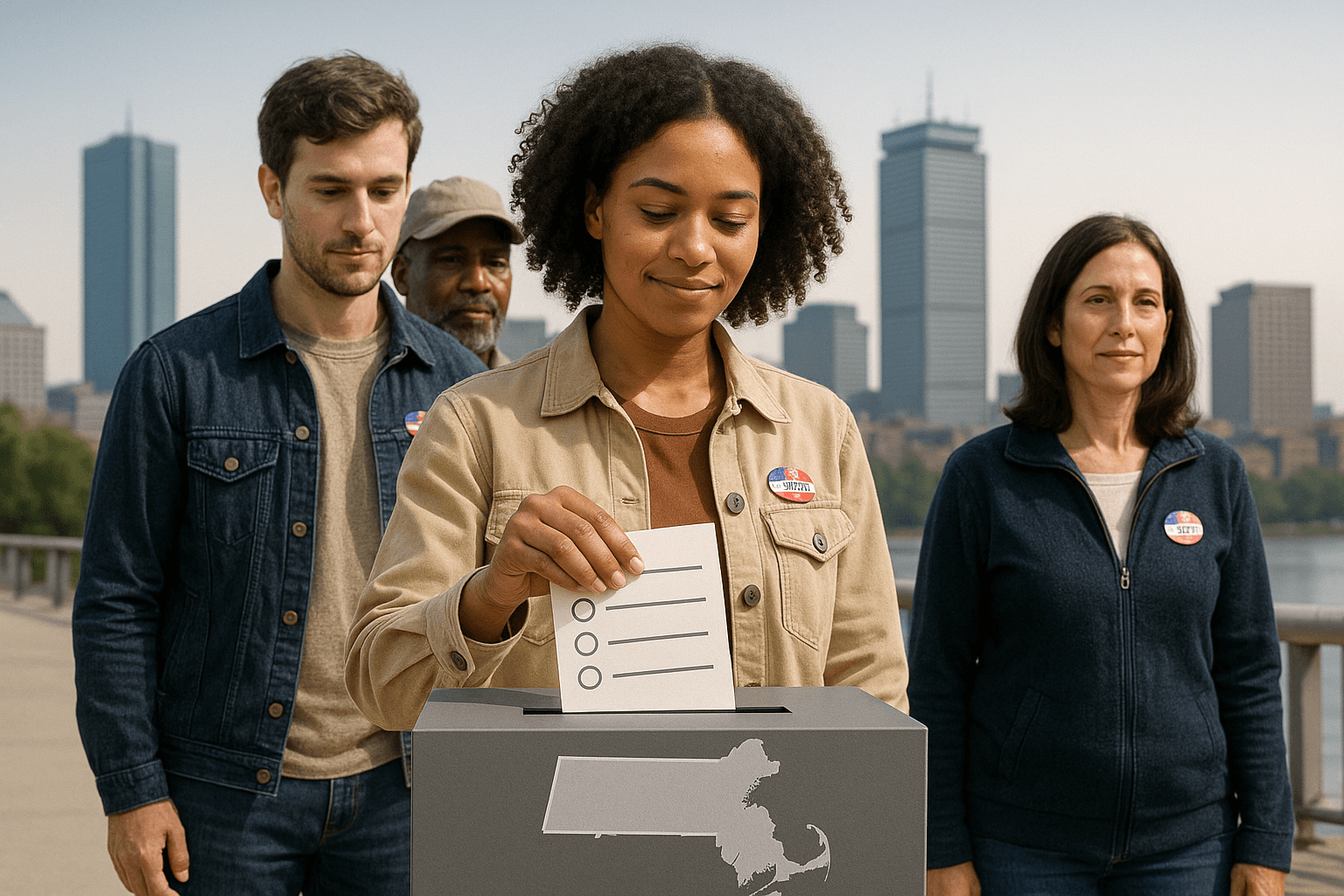

Since voters in Georgia passed an amendment that would bring back a state commission board to decide the fate of charter schools, opponents question whether voters have handed the state more control of local school systems. State residents voted 58 percent in favor of the Georgia charter school amendment which would reinstate a commission that examines charter school applications rejected by local school boards. The new law would allow the Georgia Assembly to rewrite the state constitution and allow the commission to become a permanent third party, or alternate authorizer, to override local school board decisions and offer a way for charter schools to gain approval.

Charter amendment opponents see the shift in decision-making power between local school boards and the state as way to pull funding from already financially-strapped districts. Advocates say that the goal of charter schools is to provide an alternative learning environment for underserved students in failing school districts and offer parents school choice. Yet the question at hand is not whether charter schools should exist; currently, Georgia has 160 active charter schools. Rather, the question is whether another state agency should be created to make changes to the state’s education system.

Prior to this amendment, local school boards were the primary authorizer of charter schools in their districts. Rejected charter applicants could appeal at the state level through the board of education. In 2008, the Georgia General Assembly created a state charter school commission, but it was quickly shut down in 2010 after the state Supreme Court ruled that the commission was unconstitutional because it diverted the creation of charter schools away from local school boards.

The new seven-member commission would be appointed by the state board of education through nominations from the governor, lieutenant governor and the house speaker. This concerns those critical of the new law as it grants the state the power to choose members, as opposed to a local board of education where voters pick who sits on the board. The commission would be tasked with deciding on appeals from charter applications rejected at the local level, as well as have the power to directly approve charter schools that have a statewide attendance zone, like online schools.

According to the amendment, the Georgia constitution would now define public charter schools as “special schools” and allow them to receive limited state funding, which were at the heart of the Supreme Court ruling. Public school systems would not go empty-handed as the amendment reaffirms that local school boards are authorized to approve charter schools, while local tax dollars could not be allotted to charters without local approval. It also limits certain state funds from being eliminated from district budgets if students enroll in neighboring charter schools.

This sweeping change to Georgia’s constitution comes at a time when the state has been grappling with a reduced budget, causing local school districts to cut teaching positions and look for other funding resources to shore up deficits in their budgets. Additionally, Georgia is transitioning public schools to the federally-approved Common Core State Standards curriculum. Opponents see another state agency as more wasted taxpayer dollars that pull money away from the real goal of raising education standards and student achievement.

The law will go into effect on January 1 to prepare for the commission's February start date, but some legislators have already united to challenge the decisions.

State Sen. Emmanuel Jones (D-Decatur), along with the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus, of which he is the chairman, joined a lawsuit filed by other Georgia residents in October that cites vague wording of the amendment on the ballot as having been misleading to voters. Jones believed that the wording of the ballot led voters to think they were voting for the establishment of charter schools and not the creation of a state commission. Voters in his Democratically-strong district voted more than 60 percent in favor of the amendment. Whether this lawsuit will go through before the law or commission begins is uncertain, though it reveals a schism between voters as to how to best educate Georgia students.