Here We Go Again: Why the Threat of Government Shutdowns Always Looms

Editor's Note: This piece originally published on The Independent Center's website and has been republished on IVN with permission from the organization.

The reason why we have government shutdowns is because Congress fails to complete its work on annual appropriations bills; sometimes in part or the whole.

Before going home for Christmas, Congress passed a continuing resolution to fund the federal government through Friday, March 14, 2025. This was essentially a stop-gap measure to buy Congress more time to negotiate a full-year funding bill. Those discussions between leading House and Senate appropriators are underway as Congress looks to avoid a government shutdown.

Those negotiations may have more turbulence than usual because of the likely unlawful order that the White House Office of Management and Budget issued on January 27 pausing federal loans and grants. No legal authority was cited in the order. The order violates the Impoundment Control Act, and a federal judge issued a temporary injunction against it. I wrote about the Impoundment Control Act and the administration’s plans to challenge the law in December. Although the Office of Management and Budget rescinded the order, the White House indicated that it plans to implement the directive and only rescinded it to end the court case.

The administration's controversy doesn’t bode well for getting a full-year appropriations bill out of Congress. First, Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) was always going to need Democratic votes to get a consolidated appropriations bill out of the House. Why? Because there’s always a group of Republicans who vote against consolidated appropriations bills. Consolidated appropriations bills often include legislation unrelated to appropriations. Those are known as an “omnibus bill.” The group of Republican defectors could be a dozen. It could be substantially larger.

Regardless of the exact number of defectors, whether a few or three dozen, Johnson can afford to lose only one Republican on any vote, assuming all members are present and voting. Right now, Democrats have 215 seats, assuming none of them flip on a vote. Currently, Republicans have 219 seats, but they’ll lose Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY) when she’s confirmed as the United States Ambassador to the United Nations. After Stefanik resigns, Johnson can’t afford to lose any Republicans on a vote until the special elections for the two vacant seats in Florida are completed on April 1.

Second, things aren’t much easier in the Senate, where 60 votes are needed to advance appropriations bills. Republicans have 53 seats, and not every Republican will vote for a consolidated appropriations bill. Democratic votes will be absolutely necessary in the Senate, too.

Although things could change, Democrats may be less likely to vote for a full-year appropriations bill that won’t be “faithfully executed,” to quote from Article II of the Constitution, by the White House and administration. And regardless of the suggestion from House Appropriations Committee Chairman Tom Cole (R-OK), appropriations bills are binding law. It’s a constitutional obligation outlined in Article I, Section 9, which states: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

That text from the Constitution is why funding the federal government is a continuous issue, in addition to other laws and interpretations of law. But this latest drama is only another example of the bad soap opera surrounding funding the federal government. Congress goes through it every year. Congressional leadership creates an emergency–what some would call “governing by crisis”–with the threat of a shutdown to get members in line to vote for a massive piece of legislation that no one has had time to read before they’re expected to cast their votes.

Why Do We Experience Government Shutdowns?

The reason why we have government shutdowns is because Congress fails to complete its work on annual appropriations bills; sometimes in part or the whole. Congress often averts these shutdowns through continuing resolutions (CR), which extend existing appropriations for a specified period of time. These are stop-gap measures. Most Members of Congress don’t like CRs, although they’ll go along with them to avoid a government shutdown.

But more specifically to the question, we have government shutdowns because of the Constitution and the Antidefiency Act. Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 of the Constitution states, “No money shall be drawn from the treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law.” Essentially, the federal government can’t spend what Congress hasn’t approved. Originally passed in 1884, and since significantly amended, the Antideficiency Act (31 U.S.C. §1341) prohibits the federal government from spending money that hasn’t been appropriated. The District of Columbia is also subject to the Antideficiency Act because it receives appropriations from Congress.

The interpretation of the Antideficiency Act that still applies today was written in April 1980 by then-Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti. He wrote, “On its face, the plain and unambiguous language of the Antideficiency Act prohibits an agency from incurring pay obligations once its authority to expend appropriations lapses.”

When Congress fails to pass appropriations bills on time, it leads to a lapse in funding. Affected agencies must shut down. Employees do not receive pay, even if they are classified as “essential workers” and continue to work during the shutdown. Historically, both furloughed employees and those who work during the shutdown have received back pay for its duration. Since government shutdowns mainly involve discretionary spending, mandatory programs like Medicare and Social Security continue to provide benefits to existing enrollees, although new enrollments cease for the duration of the shutdown.

Why Has Passing Appropriations Bill Become So Hard?

The budget and appropriations process that Congress currently utilizes was created in the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, also known as the Budget Act, which can be found in Chapter 17, Chapter 17A, and Chapter 17B of Title 2 of U.S. Code.

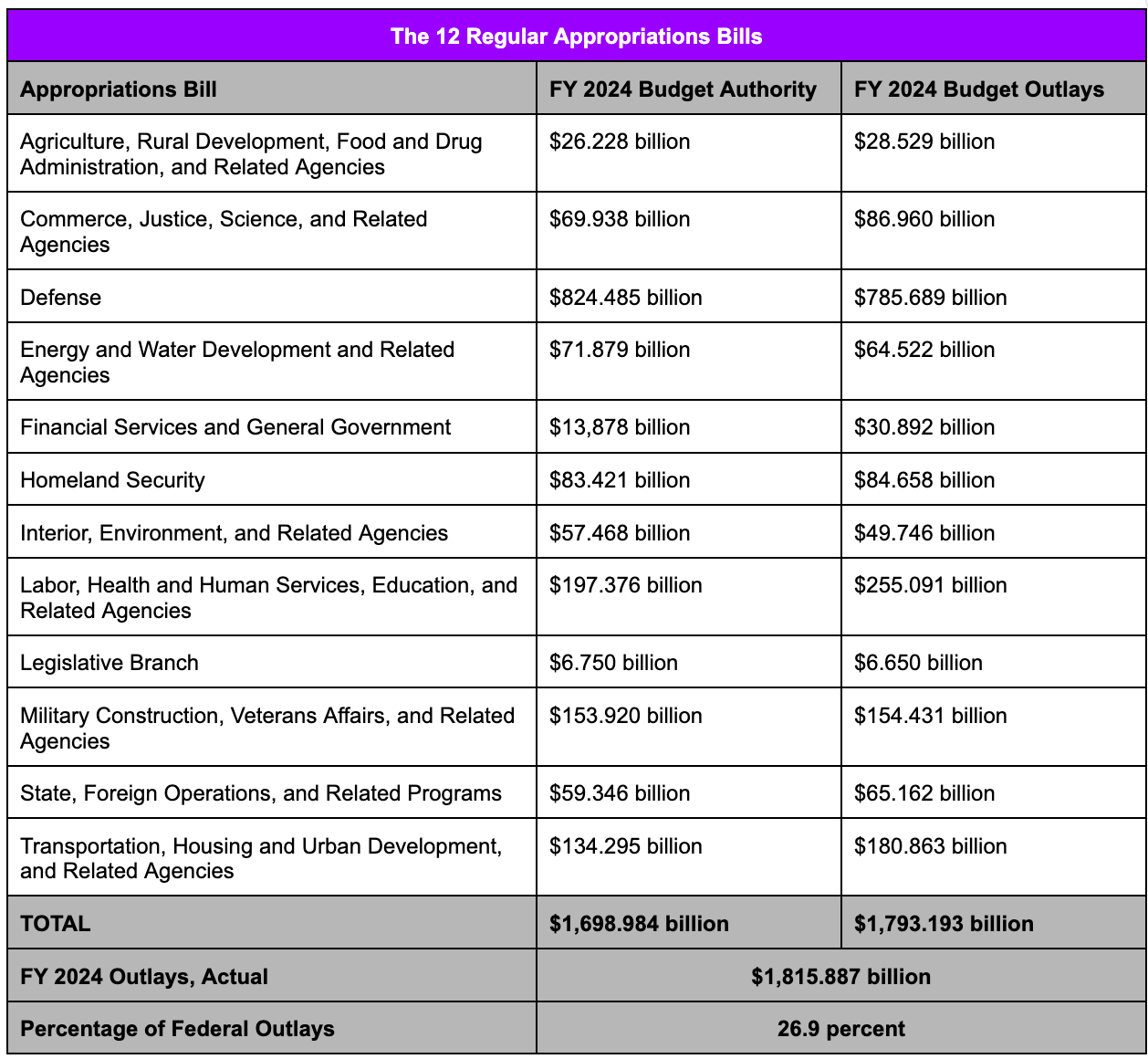

In theory, Congress passes a budget that sets topline defense and nondefense discretionary spending, then passes the 12 regular appropriations bills to fund the government. Each one of these appropriations bills funds specific departments, federal agencies, and/or programs. The House and Senate Appropriations committees have subcommittees dedicated to each one of these appropriations bills. Each bill goes through the markup process at the subcommittee and full committee level before reaching either chamber's floor.

The 12 Regular Appropriations Bills

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Note: Budget authority is the amount of dollars federal agencies may obligate. Outlays are what’s actually spent by federal agencies. Budget authority may be lower because of authority granted in a previous year. “FY 2024, Actual” is the total amount of discretionary outlays made in FY 2024, which includes dollars appropriated outside the normal appropriations process, such as supplemental appropriations bills. Congress passed two supplemental bills in FY 2024. Discretionary outlays don’t include the most significant part of federal spending, which is mandatory outlays, or net interest on the share of the debt held by the public.

Under Section 300 of the Budget Act (2 U.S.C. §631), there’s a timetable that Congress is supposed to follow for the budget and appropriations process. The timetable states that Congress may begin the consideration of regular appropriations bills on May 15. The last regular appropriations bill should leave the House by June 30. The new fiscal year is set to begin on October 1.

We hear a lot about “regular order,” but neither party really follows it, and those who tend to complain about the lack of regular order go silent when it’s politically convenient. You’ll be shocked to learn that Congress has a record of failure when doing its most basic legislative function, and the problem has gotten progressively worse over time. Congress has passed all regular appropriations bills before the October 1 deadline only four times since the Budget Act was implemented: FY 1977, FY 1989, FY 1995, and FY 1997.

Congress has routinely failed to pass the regular appropriations bills on time. However, since 2011, Congress has gone literal years without passing a single appropriations bill before the end of a fiscal year. Currently, Congress hasn’t passed any of the regular appropriations bills since FY 2019. So, it has been five years since Congress has passed any appropriations bill on time. Let me put it another way. Since FY 2011, Congress has enacted only six of the regular appropriations bills on time.

Increasing hyperpartisanship in Congress is the biggest part of the problem. It’s why government shutdowns—or at least the threat of government shutdowns—have become more frequent. The appropriations process has become another place for “gotcha” votes that one side or the other can use as a bludgeon against vulnerable Members during an election. We see this all the time. Although thoughtful amendments are offered, many are made to address some hot-button issue that appeals only to one of the parties’ bases. In recent years, culture war issues have increasingly appeared in the amendment process. Although some of those “gotcha” amendments may pass the House, they’re virtually always stripped out when the House and the Senate settle on a consolidated appropriations bill or when Congress passes a CR.

How Do We Fix the Problem?

I wish I could say there was hope of overhauling the appropriations process, but I don’t see how that happens in the near future. Part of the problem is that congressional leadership hasn’t prioritized addressing the problems with the process. Is that because “governing by crisis” benefits congressional leadership? It’s possible. Most major legislation, including consolidated appropriations bills or omnibus bills, is controlled by congressional leadership.

There have been proposals for an automatic CR in the event of a lapse in appropriations. For example, Sens. James Lankford (R-OK) and Maggie Hassan (D-NH) introduced the Prevent Government Shutdowns Act, S. 135, during the 118th Congress. Unfortunately, although the bill had bipartisan support, the legislation didn’t move for such proposals. That’s mindboggling, but passing the Prevent Government Shutdowns Act would take away a political tool to hammer the other side. The public tends to blame Republicans for government shutdowns, even in the rare instance when it wasn’t their fault.