From Grassroots Movement to Major Party: A Brief History of the Independent Party of Oregon

In February, IVN.us reported on the possibility that the Independent Party of Oregon might be named Oregon's third major party by registering 5 percent of the state's voters by August 17 of this year.

In August, officers of the Independent Party of Oregon were notified by the Oregon secretary of state that the party has now hit that goal and will be recognized as a major political party for the 2016 election cycle. As the party secretary, I thought it would be a good time to share a brief history of the Independent Party and start a conversation about what the IPO’s emergence could mean for the independent movement in this country.

The Independent Party of Oregon began as an independent voter movement to protect rights that were being trampled by the Oregon legislature.In 2005, the state legislature doubled the number of signatures needed to qualify by petition for public office and replaced the word “independent” with “non-affiliated” as a descriptor on the ballot for such candidates. These laws were pushed primarily by the Democratic Party of Oregon in response to Ralph Nader’s attempt to qualify for the Oregon ballot in 2004, and to prevent a widely anticipated independent gubernatorial bid from State Senator Ben Westlund.

The people who formed the Independent Party of Oregon testified against those measures. And, after failing to stop the legislation from passing, collected 30,000 signatures in 2006 to form the Independent Party of Oregon, which was first recognized as a ballot qualified minor party by the secretary of state in January 2007.

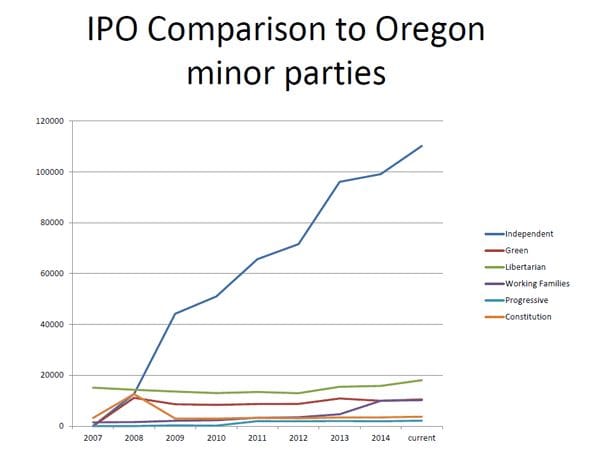

The original intent was to provide ballot access for candidates and legal standing in case the legislature decided to make a similar move against the ballot access of Oregon's minor parties. There was no real expectation of being recognized as a major political party since, although Oregon has relatively open laws for the formation and maintenance of minor parties, and despite the fact that the state has a relatively large number of functioning small minor parties (Libertarian, Pacific Green, Constitution, Working Families, Progressive), none of these parties has ever grown larger than 20,000 members, and the current largest minor party has around 15,000.

The Independent Party has bucked that trend. In 8 years, the IPO has grown to 110,000 members -- more than double the growth of Oregon Democrats and Republicans combined during that same period.

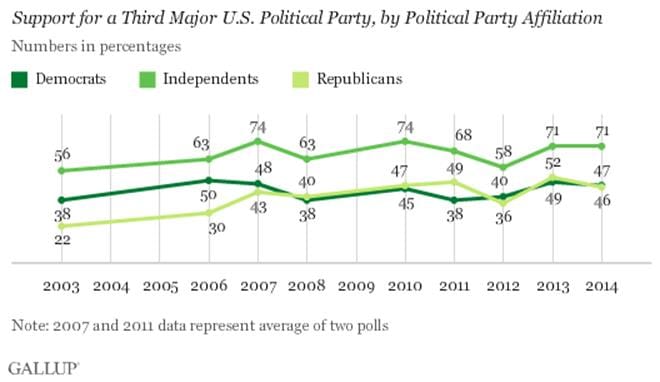

This rapid growth was primarily driven by voter frustration and the fact that an “Independent Party” now existed in Oregon. According to recent polling, only one-third of Oregon voters feel well represented by the Democrats and Republicans compared with 40 percent who believe a third party is needed.

After years of claiming that “almost no” IPO members joined purposefully, in May 2015 the House Democrats released a poll that showed 22 percent of Independent Party members believed themselves to be registered non-affiliated. More than half surveyed in the poll identified themselves as Independent Party members without prompting.

The Independent Party released its own poll a month later showing that 11 percent of Oregon voters identify as Independent Party members, even though the party’s actual membership is only 5 percent of registered voters, that 22 percent of voters would consider joining the party and a total of 80 percent would join or consider voting for Independent Party candidates.

The rapid growth of the party was not fueled by massive voter registration efforts, but merely by the presence of the Independent Party being an option on the ballot and the voter registration card. Democrats and Republicans claim voter confusion, but the reality is that voters *want* an Independent Party option. 11 percent of Oregonians identify as Independent Party members, even though only 5 percent of voters are currently registered with the party.

For the people who formed the party, this created an ethical dilemma: Could a relatively small number of officers claim to speak for a much larger number of people unless they asked members what they actually thought about candidates and issues? The answer is "no," obviously. So the party opted for democracy.

After nominating candidates by caucus in 2008, in 2010 the IPO financed its own statewide primary and opened it to any candidate who chose to seek the party’s nomination. In 2009, the party worked to pass a "fusion voting" law that allowed candidates who received more than one nomination to list up to three of those nominations on the general election ballot.

This resulted in a large number of Democratic and Republican candidates, especially incumbents, seeking the party's nomination, particularly for state legislative office. and especially in the most competitive districts.

From 2010 to 2014, as a minor party, the IPO conducted three binding statewide primary elections using the Internet to deliver ballots. It was the first political party in Oregon to conduct primary elections at its own expense, and the first political party in the United States to conduct a binding multi-jurisdiction statewide election using the Internet to deliver individualized ballots.

During that period, major party candidates in the most contested state races including governor, secretary of state, and competitive state legislative races sought the IPO nomination.Although IPO led all minor parties in running its own candidates for state legislative races and local nonpartisan office, the presence of these candidates generated far less interest or attention from the press relative to candidates of statewide significance who had been cross-nominated by the party.

The presence of major party candidates on the IPO ballot greatly raised the visibility of the party on a statewide basis and resulted in significant amounts of money being spent by Democrats and Republicans seeking the IPO nomination as a way to broaden their appeal and to distance themselves from their own party brands. This did not result in significantly increased influence at the Oregon legislature, though the party has had some modest legislative successes.

Member participation rates in these elections was relatively low, but consistent with Internet voting in other jurisdictions. The largest complaint from members was that the party did not have enough of our own candidates and many people did not want to vote for D's and R's.

As part of its elections, IPO opted to use a series of preference surveys to determine the party’s platform and agenda. Since 2010, the party has conducted two to three preference surveys during each two-year election cycle that ask members to weigh in on of issues they would like the party to prioritize.

These surveys begin with generic categories in the initial survey and are narrowed down or associated with specific legislation under consideration at the Oregon legislature.

Over a six-year period, the following general agenda has emerged:

For 2015, the top priorities were as follows (with percentages of member support):

83.7% - Require that political advertisements identify their main sources of funding.

79.0% - Increase vocational training opportunities for students in high school and community college.

74.4% - Ensure that tax dollars spent to encourage economic development return more benefits to the public than they cost.

73.4% - Establish limits on political campaign contributions.

68.3% - Look at ways to make college more affordable.

More than 1700 IPO members participated in adopting the following platform statement:

The Independent Party of Oregon favors reducing special interest influence over our government processes; increasing transparency in government, particularly with how our tax dollars are spent and how the public's business is conducted in Salem; protecting Oregon consumers, particularly with respect to banks, insurance companies and private utilities; providing incentives for small businesses to thrive and for larger businesses to expand in Oregon in a way that returns more benefits to the public than it costs.

The party’s use of a statewide primary system as a vehicle for its members to select their priorities allowed the party to associate policy preferences with ideological leanings. The policy positions preferred by IPO members were supported relatively evenly by voters who preferred more conservative candidates as those who preferred more liberal candidates.

This strongly suggests that the party’s core issues enjoy broad support among the general electorate, and herein lies one of the ways that the Independent Party represents a threat to the country's dominant parties:

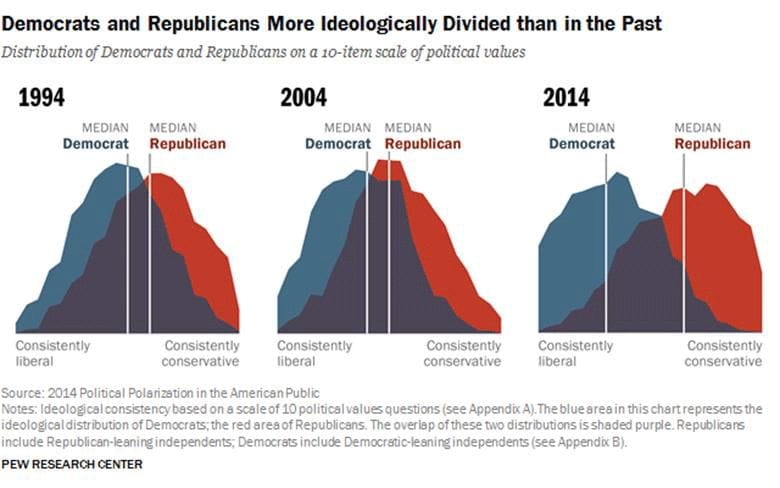

Both the Democrats and Republicans are beholden to special interests such as social conservatives, social identity organizations, labor unions, business lobbies, and other special interest groups. Fidelity to the concerns of those organizations is central to the success of candidates and leaders within the structures of both parties.

We can see graphically how these interests have pushed each party to the left and right, respectively, and how this has created space in a nonpartisan or transpartisan center.

By contrast, the IPO's method of determining priorities is designed to align, not with any special interests or the particular bias of a single candidate, but rather with issues that its members, whose views span the political spectrum, agree on.

The party's approach eschews taking positions on hot button issues in favor of finding the common ground between people of liberal and conservative orientations and seeks to "scratch the itch" of unmet need among the general electorate as a result of the degree to which both Democrats and Republicans are beholden to the special interests that fuel their apparatuses rather than the general public.

The officers of the party would like to encourage others in the independent movement to consider the efficacy of forming “independent parties” in places where that is possible around the country. Massachusetts, Hawaii, New Mexico all have nascent Independent Parties. But more importantly, we encourage the leaders of such parties to use data-driven models, such as member preference surveys to establish the platforms and agendas.

In many places like Oregon, independents forming their own political parties can be used to eliminate barriers to seeking public office but it can also be a tool for making our government more responsive to independent voters and to the general public.

One of the core sources of dissatisfaction that voters have with the dominant parties -- the reason they are now finally open to “independent” and third party alternatives -- is that they are not responsive enough to the desires of the general public.

Let's take advantage of this historical moment and bring rationality and the public interest back to the fore of our political process and do it in a way that helps to build an independent movement that reflects the will of the people and provides candidates with a path to win public office.

SAMPLING OF PRESS COVERAGE (HISTORICAL):

Independent Party may gain major party status - 2015 Portland Tribune

Independent Party qualifies for major party status; looks forward to state-run primary - Oregonian, 2015

Independent Party of Oregon comes under fire from states Democratic and Republican parties - Oregonian -

Oregon is better than anywhere else... - Rachel Maddow 2015 - Maddow discusses weird news from Oregon, including IPO hitting major party status.

Independent Party of Oregon to have open primary - AP/Statesman-Journal - Discusses that IPO will open election to non-affiliated voters.

Former Secretaries of State Slam Attempt to Kill Independent Party - Willamette Week, 2011 - Discusses Democratic "IPO death penalty bill", an attempt to force IPO to change its name or be disbanded.

Bonamici, Cornilles debate job creation - KATU, 2011 - KATU's coverage on the televised Congressional special-election debate, co-hosted by the Independent Party of Oregon and televised on Portland network television.

An Experimental Primary - Register-Guard, 2010 - Eugene Register Guard editorial board discusses historic IPO primary election.

Oregon's Independent Party on cusp of power, identity crisis - Oregonian, 2010 - Discusses emergence of IPO.

How Would Fusion Voting Change Oregon Politics - Oregonian, 2009 - Discusses possible consequences of the fusion voting law that I helped to pass in 2009.

A Party Born of Outrage - OPB, 2007 - discusses how IPO was formed in response to Democrats and Republicans trying to make it harder to run for office as an independent and removing the word "independent" from the ballot in response to Ralph Nader's Presidential campaign and Ben Westlund's rumoured independent run for governor.

Photo Source: AP