For Good or Bad, Primary Changes May Be Coming to Elections Near You

Photo Credit: Getty Images / Unsplash

The last couple of years have seen an increase in states looking to change their primary election laws. In some cases, party leaders are trying to increase their power over electoral outcomes, while nonpartisan reformers attempt to offer other states better elections.

The focus on primaries has become so prominent that the National Conference of State Legislatures recently took notice of it in a report in which authors Adam Kuckuk and Ben Williams acknowledge "higher than normal" attempts to change primary election rules.

"States rarely amend their primary systems," they write. "On average, just one state switches primary types every two to three years, and these changes have tended to make the primary more open—but not always."

The last four years have seen an uptick in activity.

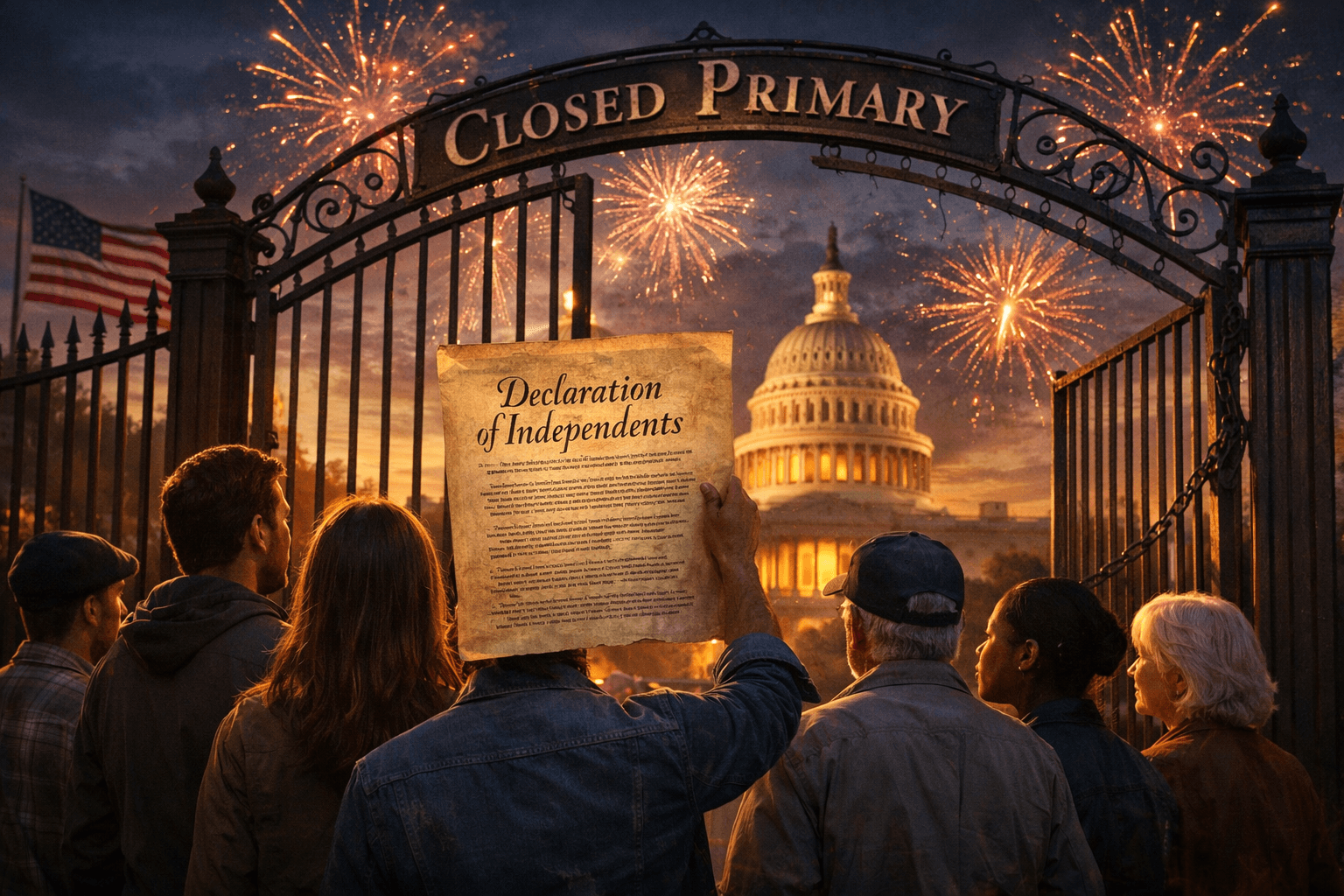

Three states in the last two years have acted to increase the influence party leaders have over elections. Louisiana is the most recent example, where state lawmakers dismantled a popular nonpartisan election system in favor of closed partisan primaries for US Senate and House elections and some statewide elections.

It changes a system that serves the public interest of electing candidates to a system that serves the private interest of selecting party nominees on the taxpayer's dime.

Kuckuk and Williams also mentioned Tennessee, where in 2023 lawmakers added a criminal penalty for voters who vote in a party's primary who are not "bona fide" members of that party. Voters can be charged with a misdemeanor or felony (depending on the situation) for exercising their right to vote.

Ahead of the March presidential primaries, Tennessee voters have expressed confusion to poll workers over what "bona fide" means. The reported response many of these voters get is signs posted at the polling site speak for themselves -- when they clearly don't.

Wyoming changed its laws in 2023 to eliminate the option voters had to change their party declaration at the polls on primary election day or up to two weeks before the primary election, Instead, the deadline to declare a party is a full 3 months ahead of the election.

Anyone familiar with electoral politics knows much can change in 3 months.

The reported reason why Wyoming changed its registration requirements is fear by the Republican majority of crossover voting. Crossover voting occurs when voters cast a ballot in a party' primary election when they are normally affiliated with another party.

Party leaders argue that voters use this as a strategy to infiltrate the opposing party in order to prop up weaker candidates. This argument has been used by both major parties to justify existing closed primaries or to push for closing these taxpayer-funded elections.

Republicans and Democrats have even turned to the courts to argue that open primaries violate their constitutional rights. Yet, Democrats in Hawaii and Republicans in Colorado were not able to produce evidence that crossover voting has any impact on primary outcomes.

In fact, whenever open partisan primaries are challenged in court, the party or parties leading the effort always fail to produce evidence that would satisfy any burden to their associational rights.

Research into the matter points to most claims of crossover voting being overblown. They were in Wyoming when former President Donald Trump and his allies in the Republican leadership warned that then-US Rep Liz Cheney was courting Democrats to pull out a win.

Cheney lost in the primary by 37 points.

Research has found that when evaluating voter motivations in the few instances of "crossover voting" through exit polls and other survey methods, nearly all participants in a party's primary do so to vote for their first-choice candidate or to vote in a way they think will matter. Not to sabotage a party.

Still, party leaders cite "crossover voting" as a threat to their rights and the reason to move to closed primaries in states like Texas and Mississippi.

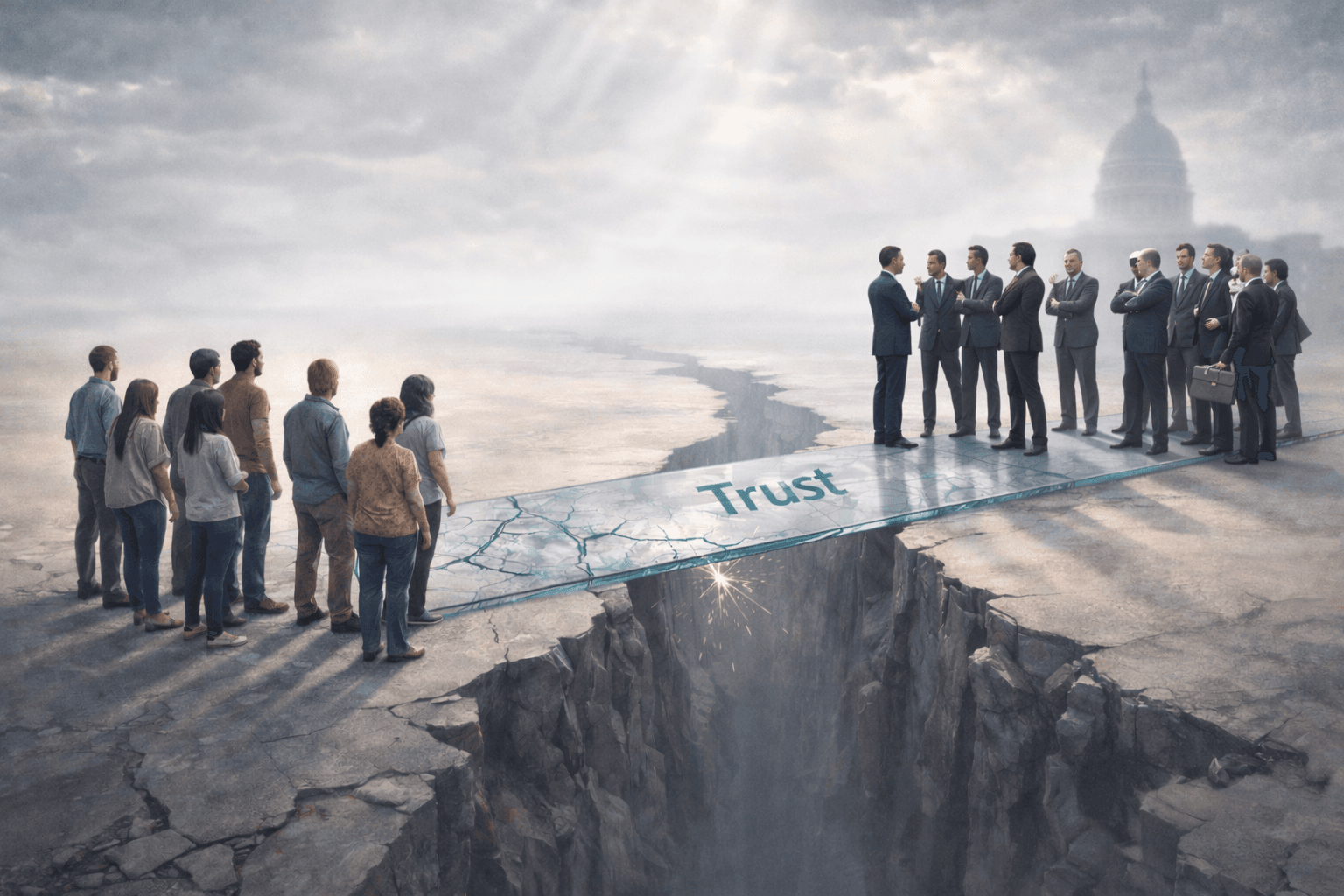

This only scratches the surface on the focus that has been put on primary elections, because the parties know how critical these elections are in the process. They know that the primaries are key to preserving an election system that serves their interests first.

And because the parties have designed the current electoral system -- nearly 24 million independent voters are shut out of taxpayer-funded elections in 2024. The number rises to 27 million when third party voters are added.

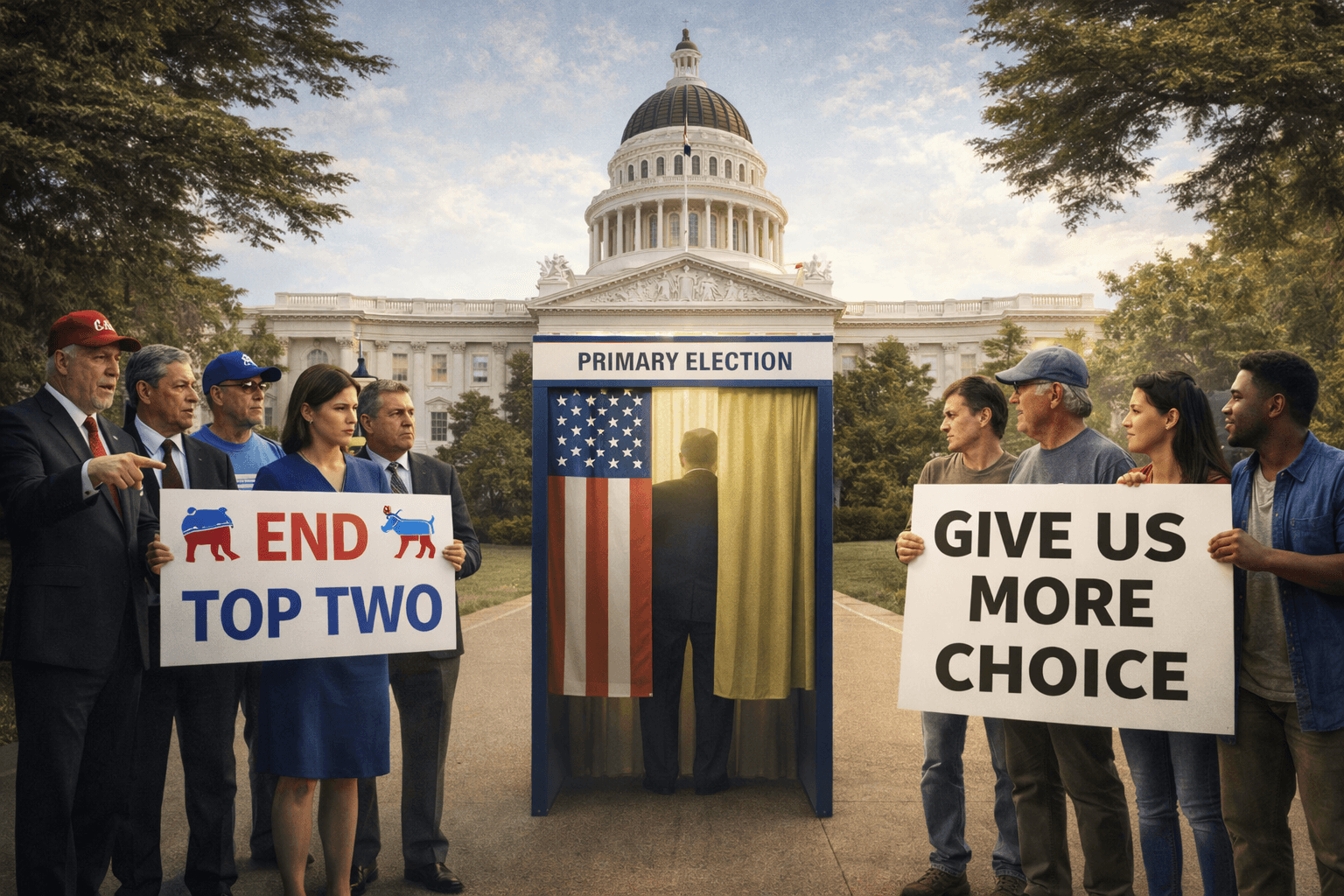

But, for all the bad that is happening with primary elections across the country, there is also plenty of progress being made.

Alaska voters approved a nonpartisan top-four system in 2020 that allows all voters and candidates to participate on a single primary ballot and the top four vote-getters move on to the general election. The reform was combined with ranked choice voting in the general.

The new system was used for the first time in the 2022 midterms and after a single election cycle it has shown the benefits and potential of an election system that prioritizes electing responsible representatives that are accountable to the voting population at large.

Nevada voters will vote on a nonpartisan Top Five system in November. It will be the second election the initiative has appeared on the ballot as state law requires certain constitutional changes to be approved by voters in two elections. A majority approved it in 2022.

While Kuckuk and Williams mentioned Alaska and Nevada in their report, there are also active campaigns and efforts to implement Top Two, Top Four, or Top Five primary systems in Arizona, Idaho, Massachusetts, New York City, Oklahoma, San Diego, Wisconsin, and more are in the works.

Shawn Griffiths

Shawn Griffiths