Boston, Concord Want Ranked Choice Voting -- Here's Why State Law Makes It Difficult

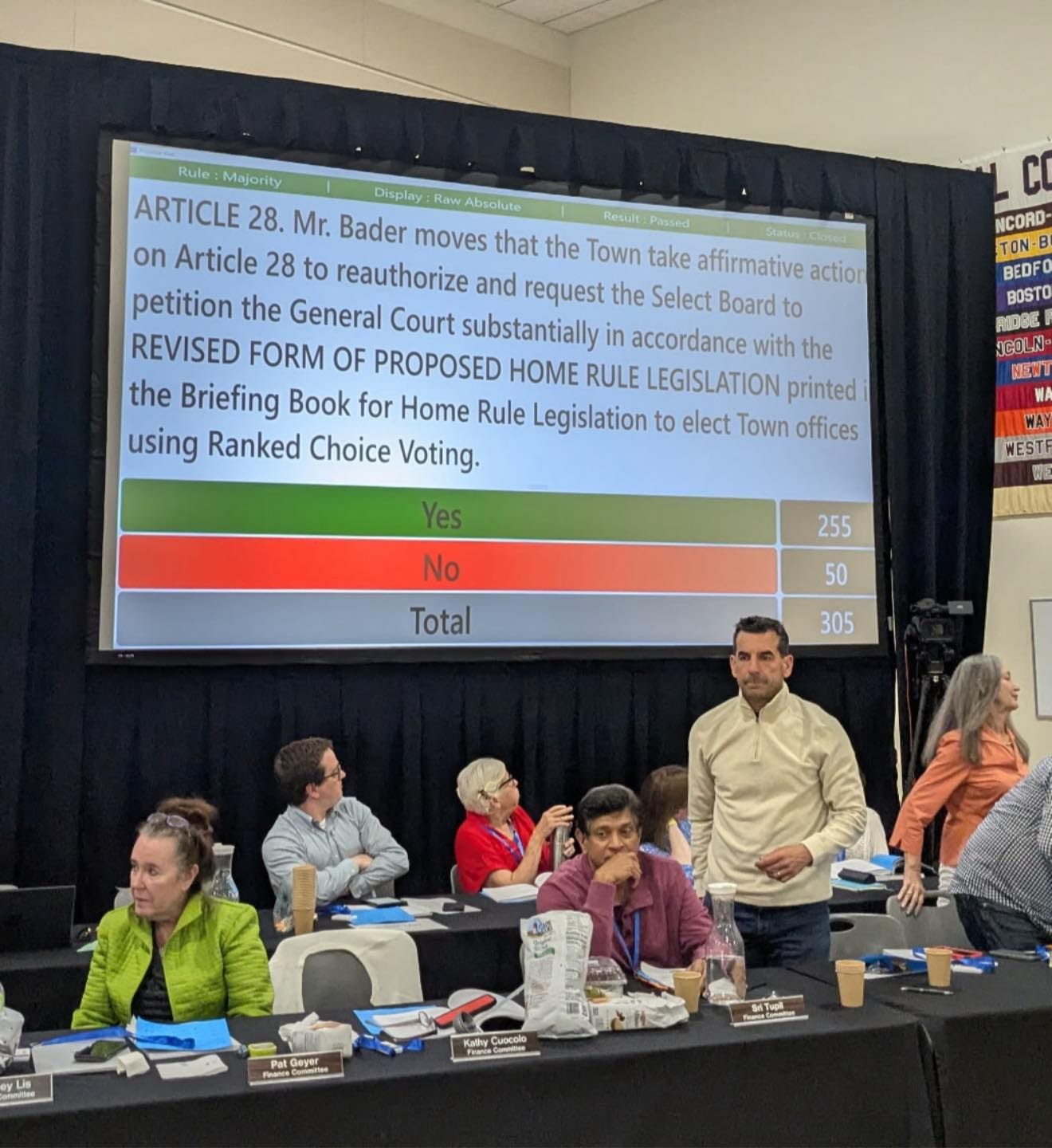

CONCORD, MASS. - Concord is the latest town in Massachusetts to signal it wants to adopt ranked choice voting after residents overwhelmingly voted for Article 28 in a town meeting Wednesday. The vote comes not long after the Boston City Council advanced its own ranked choice voting measure.

Photo of the Concord vote provided by Voter Choice Massachusetts:

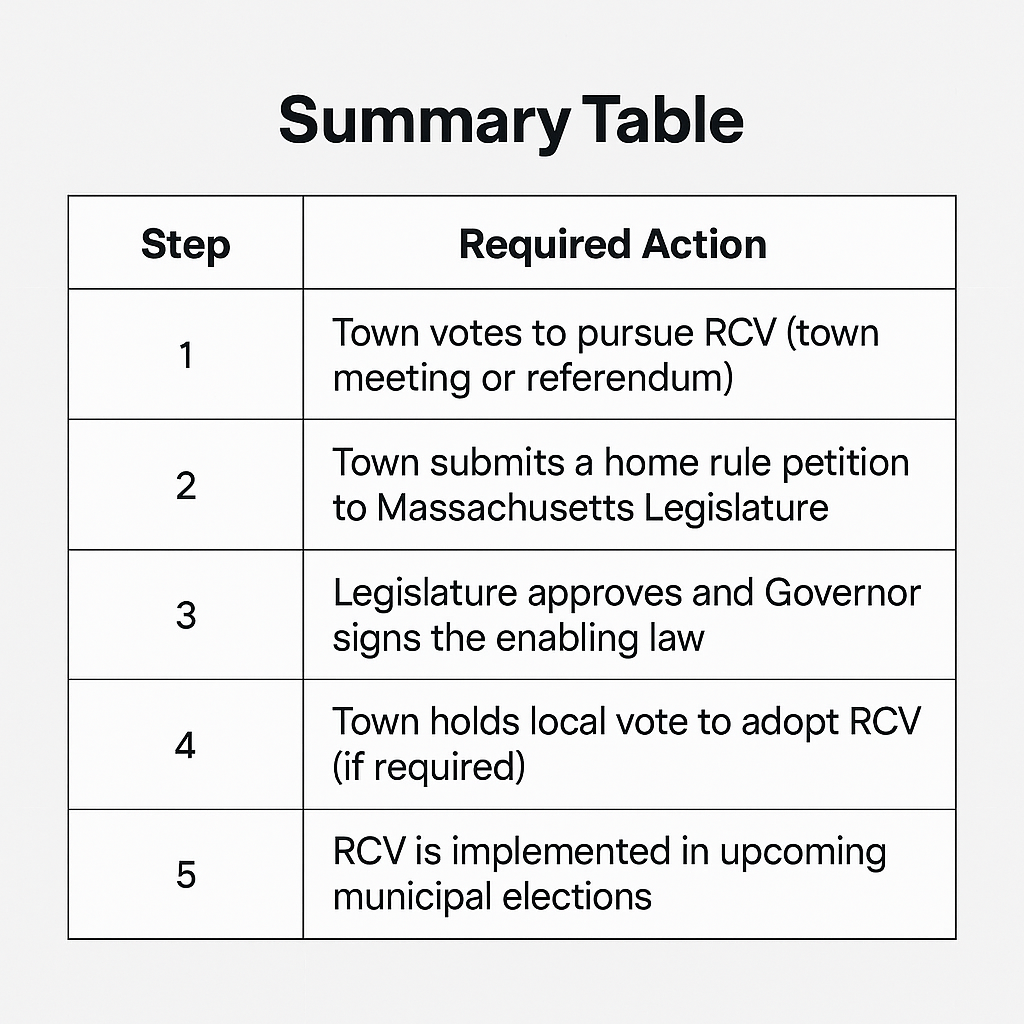

However, neither jurisdiction has the authority to unilaterally adopt ranked choice voting (RCV). Article 28 in Concord approves a Home Rule Petition that will be sent to the state legislature (called the General Court). Massachusetts law dictates that cities and towns must have approval from the legislature and governor to adopt systemic changes to their elections.

This means voting reforms like ranked choice voting, but it also includes things like increasing or decreasing the size of a city council or changing the type of primary used.

Similarly, the Boston City Council approved a Home Rule Petition for RCV that was supported by Mayor Michelle Wu. It is a cumbersome process that ultimately puts the fate of local elections in the hands of lawmakers who do not live or represent the jurisdiction petitioning to use a new voting method.

City leaders and voters cannot simply decide for themselves what election system is best for their communities. Instead, there are multiple steps that need to be taken.

But the situation gets even more frustrating for cities and towns that file Home Rule Petitions because the General Court rarely acts on them or approves them. Concord and Boston may be recent examples of jurisdictions that have filed petitions to adopt RCV, but they are far from the only ones in Massachusetts in the last few years.

And for Concord, this is not the first time residents and town officials have tried.

Concord initially filed a Home Rule Petition for RCV after it was approved by voters in 2022, but it failed to pass. Home Rule Petitions related to RCV were also filed in Amherst in 2018, Brookline in 2023, Easthampton in 2024, Lexington in January, Northampton in 2023, and Salem in 2023. All have been left pending in the legislature.

Ranked choice voting, also known as instant runoff, gives voters the option to rank candidates on the ballot in order of preference (1st choice, 2nd choice, 3rd choice, etc.). If no candidate gets over 50% of first-choice selections, an instant runoff round kicks in that eliminates the last place candidate and redistributes their voters’ next choice.

Subsequent elimination rounds are held until a candidate has at least 50%+1 of the vote. This is how the system works in elections for a single office but RCV can also be used in multi-winner races as well. Dozens of jurisdictions in the US already use the voting reform, including two states – Maine and Alaska.

In total, nearly 14 million US voters have access to RCV elections.

A campaign to implement RCV at the statewide level in Massachusetts failed in 2020 under Ballot Question 2. Yet, the increasing number of cities and towns wanting to adopt its use for at least some of their elections shows there is an appetite for electoral change in Massachusetts that could potentially be growing.

An Issue of Local Representation and Control

Advocates of RCV assert that one of its benefits is that it determines a majority winner via instant runoff preferences without the expense and hassle of conducting a separate runoff election that would likely have a much lower turnout. Instead, a majority winner can be determined in one election.

Or, in multi-winner elections, RCV can be used to ensure winning candidates reach a certain vote threshold, like for Boston’s at-large city council seats. Out of its 13 council seats, 4 are decided in a citywide vote after a nonpartisan primary advances the top 8 candidates (regardless of party) to the general election.

Under RCV, the threshold needed for a candidate to earn one of these 4 at-large seats would be 20% of the vote in a single election. While this may not sound like a lot, candidates don’t need even that much under the current system. For example, in the 2013 at-large council election, not a single winning candidate hit 20% and the fourth-place winner only garnered 13.54% of the vote.

In 2019, Michelle Wu was the only candidate to reach this threshold at 20.73% and the fourth-place winner got 11.19% of the vote. This issue doesn’t extend to the district seats where primary elections advance the top-two candidates. However, RCV advocates say it could help better determine which of the top two has the broadest appeal with voters in the primary.

There is a bill currently in the Massachusetts General Court that would provide a local option for RCV without having to jump through all the current legislative hoops. S.531, presented by Rebecca Rausch, stipulates that towns and cities that want to adopt RCV can be exempt from any Home Rule Petition requirement.

The bill was referred to the Joint Committee on Election Laws in February and has not been acted on since.

It is important to note that the Home Rule Petition goes beyond RCV reform. Towns and cities may want to make other significant changes to the way they conduct elections for their communities. However, they are denied the ability to act as their own laboratories of democracy and must endure a system that suppresses local control.

Shawn Griffiths

Shawn Griffiths