California Parole Population Decreasing Faster Than Prison Population

After the California Legislature introduced their 2011 plan to realign inmate numbers with the population capacity of prisons, the Californian correctional system has seen drastic changes. One of the most visible changes in corrections, however, is within the parolee population.

When realignment began on October 1, 2011, the system shifted the responsibility of monitoring non-serious, non-violent parolees to the counties.

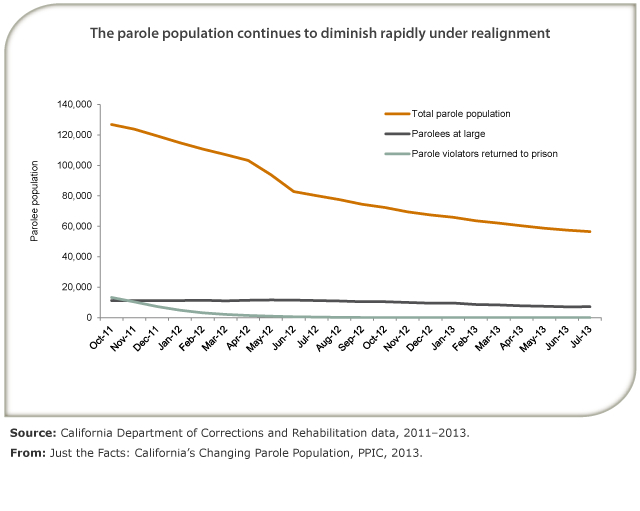

According to a study by the Public Policy Institute of California, the parolee population was already in gradual decline from a 2007 peak at 163,000 to 127,000 by the time realignment began. As of July 2013, the number of state parolees has sunk to 53,000, tripling the rate of decline in prison population.

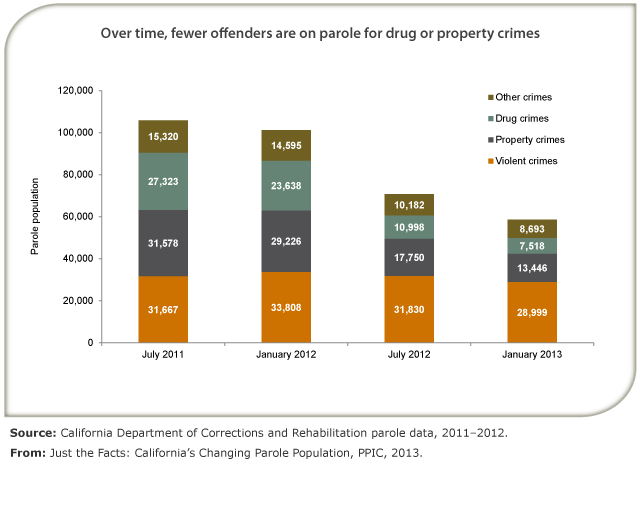

The demographics of this concentrated pool are shifting rapidly. State parole is now largely reserved for violent or serious felony charges, prompting a jump in violent or serious inmates from 50 percent to 65 percent of the parole population since last year.

Of the overall parolee population, females dropped during the same period from 9.9 percent to 7.2 percent; women are statistically shown to be more likely imprisoned for drug or property crimes than for violent crimes. There's no change to the disproportionate African American presence, however. While only making up 6 percent of the adult population in California, African Americans make up 29 percent of the parolee population.

This re-prioritization of state funds toward serious or violent charges means that while the overall number of parolees "at large" has decreased from 11,000 to 7,000, fugitives have risen from 8.8 percent to 12.7 percent. However, only 42 percent of parolees are classified as high risk to reoffend, based on their criminal history, age, and gender.

Due to realignment measures that punish parole violators with county jail, house arrest, or electronic monitoring, those that break parole are never sent back to state prison.

The counties have emerged as the unsung heroes of California's realignment effort, shouldering prison overflow and developing individualized approaches to monitoring for both pretrial detainees and parolees in reentry. These efforts have saved bed space and trail-blazed for smart-on-crimers seeking to evolve the state's efforts against recidivism.

A study by the ACLU assessing realignment in September 2012 cited Contra Costa County's success: 82 percent of low-level offenders are given split sentences, allowing the county to pursue incarceration alternatives through community monitoring and rehab. In addition, Sacramento's established a new daily reporting center serving 600 parolees a day.

According to the ACLU, there are still counties using realignment dollars to expand jails without changing policy. The scattered patchwork of counties collecting data for statistical analysis makes accurately assessing the state's progress as a whole almost impossible.

Governor Brown did not mandate data collection in the name of county autonomy, leaving data collection on recidivism at the whim of each individual county.