Will the 113th Congress Be Popular? Don't Bet On It

Credit: Wikipedia

If the 112th Congress will be remembered for being infamously the least effective Congress in over 60 years, particularly after the fiscal cliff debacle, the 113th Congress will face an uphill battle to regain the nation's popular support. Not only do congressmen and women appear to be more entangled in petty politics than ever but, most importantly, the 113th Congress is not representative of the American popular vote.

Now that vote counts have been finalized in 49 states, it appears the Democratic House candidates received 49.15% of the votes against 48.03% for the Republican candidates, a difference of 1,363,351 votes. The disparity in the popular vote would give the House to the Democrats, and the reality is in major part explained by the 2010 gerrymandering, which favors Republican candidates.

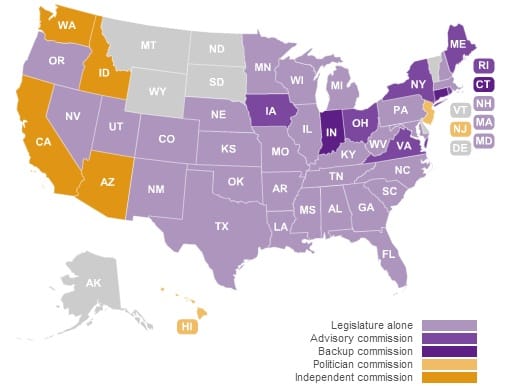

Gerrymandering is the common practice of playing on the geographical boundaries of electoral districts to create an advantage for a particular party or group of people. Both Democrats and Republicans have been using this process to increase their chances of winning for years. The redistricting process is controlled in most states by the state legislature. In a few exceptions the process is controlled by different types of commissions, including independent commissions. Credit: http://redistricting.lls.edu/

The latest redistricting occurred in 2010. It followed massive victories for Republicans in the mid-term elections, who took control of many state legislatures and thus resulted in a gerrymandering that favored Republican candidates. Columbia law professor Nathaniel Persily said, "Democrats control the line drawing for 44 congressional seats and 885 state legislative seats, while Republicans control the line drawing for 210 congressional seats and 2,498 state legislative seats."

To illustrate the extent of the unbalance, to have won the majority in the House 2012, the Democrats would have needed to win by 7.25%. In all fairness, although the latest gerrymandering turned in favor of the Republicans, Democrats would have done the same if they had had the opportunity. Despite the redistricting competition, one bi-partisan rule has always been respected: the process has to favor either a Democrat or a Republican, which naturally results in the under-representation of third party or non-partisan candidates.

40% of American voters consider themselves independents or non-party affiliated. Yet, the 113th Congress has no independents in the House and only two independents in the Senate. This is a clear indication of the lack of accurate representation in the American electoral system.

Congressional redistricting is done every 10 years, so the 2010 boundaries will continue to affect the results of the next four elections. Any major improvements in balanced representation will be difficult to attain in the near future. Does this mean that we have resolve ourselves to this situation? Not necessarily.

Recent reforms, such as the independent citizen redistricting commission in California or the new "Fair Redistricting" criteria in Florida, have blocking the redistricting process from partisan control. Both initiatives were ballot measures approved by the citizens of those states.

If it is too early to draw conclusions about the affect of these reforms, their mere existence is a symbol that voters around the country have the opportunity to prevent partisan manipulation of the electoral process.