Why Classism Concerns San Diego Educators, Hurt Students

This is the second in a two-part series. Read the first part here.

Providing preschool at the earliest stages of a child’s development can help close the achievement gap in learning for many low-income children because what’s at stake is a lack of solid preparation for kindergarten and beyond.

It begins with family poverty. If parents can’t afford to provide early childhood education for their children, those kids are likely to lag behind their wealthier peers for years.

“Having that opportunity for all our little ones is definitely going to make a difference,” said Alethea Arguilez, executive director of First 5 San Diego. “It prepares them.”

Even young children with mild to moderate cases of lagging development can be helped through intervention. “If we can get in front of it, we can help eliminate that child’s potential barriers,” Arguilez said.

Deidre Jones, vice president of early childhood development for Neighborhood House Association, said preschool matters because children will gain cognitive, social and emotional skills, which she said “are paramount, as that is the foundation for learning and behavior and is what most kindergarten teachers look for upon kindergarten entry.”

Children of color from low-income families “typically do not have the same experiences and opportunities more affluent and privileged children have,” Jones said. “Early childhood programs fill the gap.”

Engaging, hands-on, developmentally appropriate activities allow children to build the cognitive skills that prepare them for kindergarten and in this way are more prepared than those without a preschool experience, she said.

Neighborhood House Association, a Head Start grantee that operates approximately 30 Head Start sites, is one of several options for parents searching for a preschool setting for their little ones.

A structured setting is not essential, for optimal development, Arguilez said. What’s most critical “is relationships that are solid and responsive and positive to help them grow – that nurturing piece, that loving piece.”

Exposure to literacy is helpful at an early age, but what preschool can offer that’s additionally beneficial, she said, is engaging with adults and peers, social interactions, learning how to share, following the rules and healthy play.

Arguilez could not stress strongly enough how important a role parents play in their child’s early development.

“It’s the engagement of the parent or caregiver as well as the engagement of the child,” she said. “It has to happen in parallel. If it doesn’t happen in parallel, then we miss the opportunity. It’s a partnership.”

That partnership, she stressed, doesn’t end when kids start regular school, so parents need to know how to continue that learning at home because the parents are the constant in their lives.

“The family setting is critical throughout the child’s entire educational experience,” she said. “Parents are the first teachers of their children, and they need to know that what they do is going to have that profound either positive or negative impact on their child’s life.”

The Challenges of Kindergarten

The challenges are real for kindergarten teachers who have a mix of children in their classrooms, those with and those without the experience of a childcare or preschool setting.

“Talk to any kindergarten teacher and they’re going to tell you: ‘I can teach kids to learn their letters and their numbers and how to read. I can’t teach them to feel safe. I can’t teach them to feel secure. I can’t teach them how to feel loved,’” said Shana Hazan, a San Diego Unified School District parent and First 5 California commissioner.

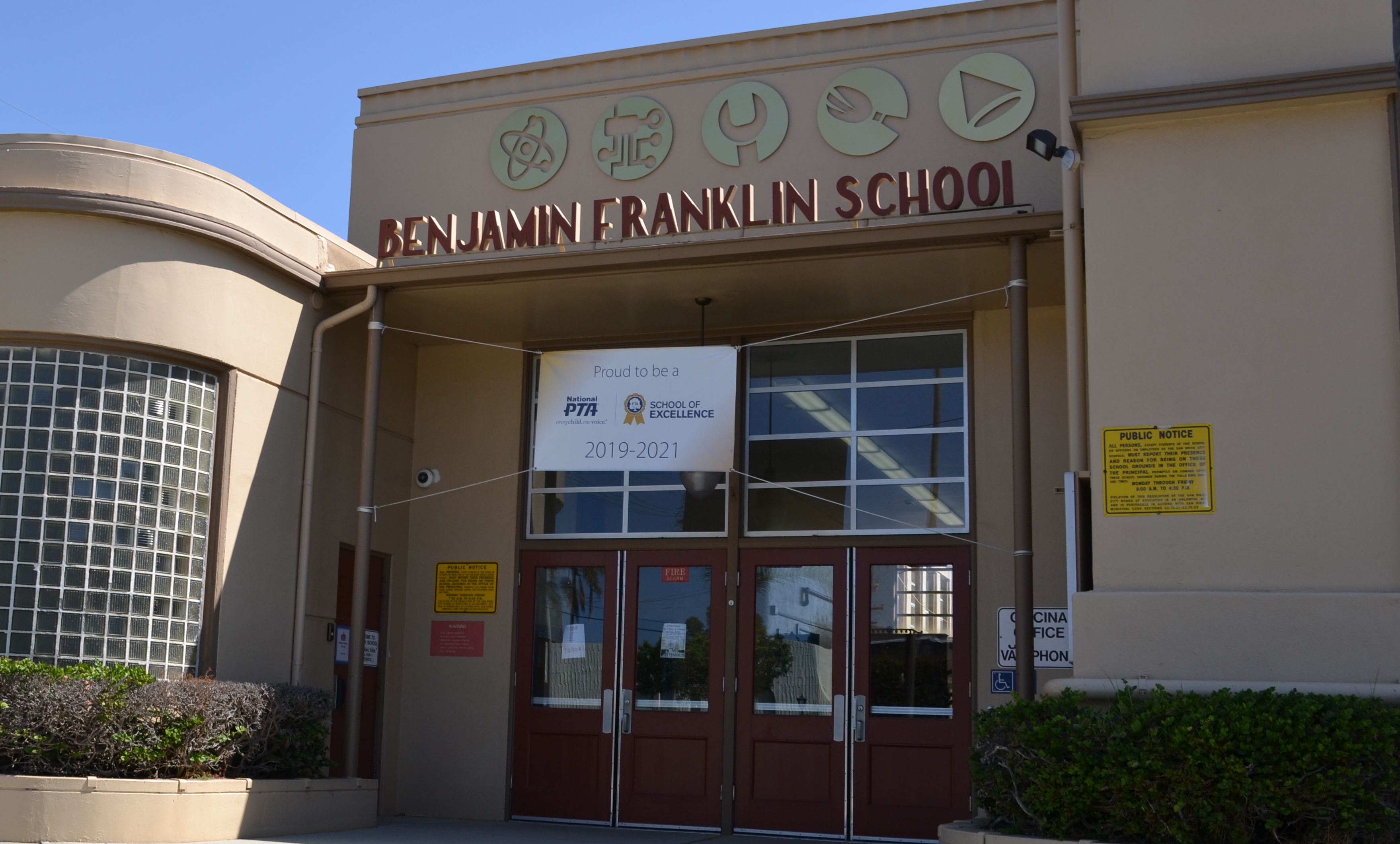

Franklin Elementary School kindergarten teacher Kachina Shanks said family and home life play an important role in a child’s ability to learn.

“There are students who may not have the best home life and can come to school and leave that all behind them and still be very successful, but I have found this to be the rare case,” she said.

Students struggle when they have anxiety or are forced to miss too many days of school, and this can cause them to lose confidence, she said. “When a child has a lot on their mind from issues happening at home, they cannot always focus in class.”

Shanks said the challenge she faces as a kindergarten teacher is understanding that students enter kindergarten with very different prior experiences.

“Students who have had previous early childhood education typically have an easier time with the social interactions in kindergarten,” she said. “They understand that classrooms have rules which they need to follow. They understand the need to share and wait their turn.”

For students lacking experience in a preschool-type setting, it takes more time for adjustment, she said.

“These students can sometimes be more emotional as they learn that things aren’t solely centered around them in the classroom,” she said.

Other challenges for these young children, she said, include a lack of stamina, inability to focus on tasks for longer periods of time, not understanding schedules for activities, difficulty following instructions and interacting pleasantly with their peers, becoming frustrated and tired easily, and being unfamiliar with early academics.

“Students who have had early childhood education often come in with a variety of skills and tools under their belt, Shanks said. “They are familiar with a routine and schedule. They have had practice with academics and using classroom tools. They have had lots of social interactions and understand that there are rules they need to follow.”

But it often doesn’t take long to bring students without preschool up to the level of those who have, once they have acclimated to a school setting.

“Kindergartners are like sponges,” she said. “They pick things up so quickly and apply it so quickly that these gaps close a great deal within the first month or two of school.”

“It is our job to help all students find a love for school and learning and get them on track to be academically and socially successful,” Shanks said. “This challenge is also one of the things I love most about kindergarten and why I wouldn’t want to do anything else.”

Segregating Children

Although First 5 San Diego does not pre-qualify families based on income levels, the organization does target certain populations including military and refugee/immigrant families, lower-income families and families of color.

Diminishing funding for some of these programs concerns Arguilez.

“Early intervention and prevention programming is at risk because funding is decreasing,” she said.

“We would have to create criteria to prioritize needs,” she said. “iIt’s unfortunate because First 5 statewide prided themselves on being able to serve all children.”

Prioritizing means determining greatest need. “But how do you define need?” she said.

For now there is no income barrier to First 5’s range of services, all of which can be accessed by calling 211 or visiting the First 5 website.

But many federally-funded or state-run programs admit children into preschool based on income level, and this troubles Arguilez.

“Why do we segregate children based on their socio-economic status?” she said. “We’re saying to families: ‘If you qualify then you go here, but if you have money then you go over there.’ Instead, why haven’t we come into this new hybrid model where we bring in all children of varying backgrounds, just like you would in a community school, a public school?”

These are old constructs, she said, that have slowly begun to change, with some First 5 grantees venturing into new childcare partnerships that integrate a fee-for-service model with early Head Start.

“I think there’s a desire to change, but the overall framework is designed like Head Start which is really for families in poverty and has really not shifted in all these years,” Arguilez said.

Her goal is to see a universal preschool program that mixes young children from all socio-economic backgrounds. Without that, preschool becomes a mirror for what public schools often look like: higher-income families grouped together at schools in wealthier communities while children from lower-income families attend different schools.

Classism in Education

Classism, the systematic oppression of subordinated class groups that advantage and strengthen dominant class groups, is where it all begins.

Racism in public education didn't just spring up on its own. It stems from the separation that exists in our class-based society that is defined mostly by income levels.

Systemic racism affects children beginning at birth if a child is born into poverty.

The Civil Rights Movement may have advanced integration in schools, but if poor Black children and other children of color don’t have early access to the advantages wealthier families provide for their children – good nutrition, quality preschool, readily available books and educational tools, a loving and stable home life – then they suffer, not just academically but often in other aspects throughout their lives.

Discouragingly, Eric Hanushek, in his 2016 Education Next article on the groundbreaking 1964 Coleman Report, wrote, “Achievement gaps remain nearly as large as they were when Coleman and his team put pen to paper.”

Writing these reports on racism in the public education system put me in mind of the tumultuous tenure of former San Diego Unified Superintendent Alan Bersin – not because it was so contentious but because the inspiration for many of his policies was a six-year-old Black girl named Ruby Bridges. She became his poster child for the urgent need for serious education reform.

In 1954, the landmark Supreme Court case, Brown vs. the Board of Education, ended segregation in public schools. Yet the racial divide remained in the South – where children in Black schools received a lower quality of education than White schools provided.

Six years later, in 1960, Bridges broke segregation boundaries by daring to enroll in her all-White neighborhood school in New Orleans, which resulted in chaos as angry segregationists attacked her verbally and withdrew their kids from the school in protest.

Gains have been made in the past 66 years to integrate schools, but what has remained is a class-based system of oppression that by its nature denies educational equity for the poor, composed primarily of immigrants and families of color.

Classism’s tentacles entangle the most helpless among us and drag them down from the moment they are born.

Poverty and discrimination continue to make the struggle for equality in public education an elusive ideal. Only when the chronic problem of poverty in America is seriously addressed can equity in educational opportunities be achieved for all children, regardless of income levels or skin color.