Thomas Massie and AOC: The Political Alliance No One Saw Coming in 2025

WASHINGTON, D.C. - All eyes are on President Donald Trump to see if the US will further insert itself into the escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran. As the two nations continue to attack each other, the debate over US involvement is creating a rift between defense hawks and non-interventionists in the Republican Party.

But it has also brought together two unlikely political allies: Libertarian Republican Thomas Massie of Kentucky and progressive Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) of New York, who together are calling on Congress to rein in the president’s ability to unilaterally thrust the US into another Middle East war.

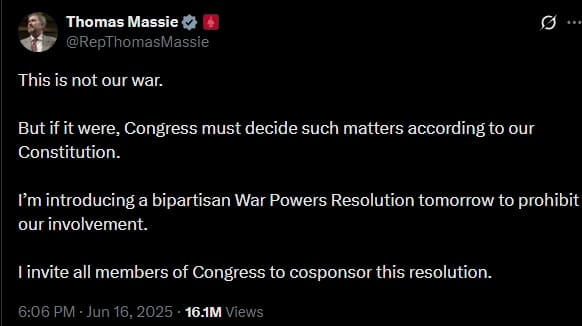

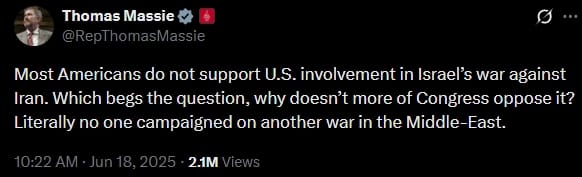

On June 16, Massie announced on X that he would introduce a War Powers Resolution to prohibit US involvement in a conflict that could change the geopolitical landscape in the Middle East and pull in other nations around the world in the process. He cited the US Constitution, which gives Congress the authority to declare war.

AOC responded to the post, saying “signing on.”

As promised, Massie introduced the resolution on June 17 with US Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) and a large list of original co-sponsors, including:

Reps. Don Beyer (D-VA), Gregorio Casar (D-TX), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), Lloyd Doggett (D-TX), Chuy Garcia (D-IL), Val Hoyle (D-OR), Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), Summer Lee (D-PA), Jim McGovern (D-MA), Ilhan Omar (D-MN), Ayanna Presley (D-MA), Delia Ramirez (D-IL), Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), and Nydia Velazquez (D-NY).

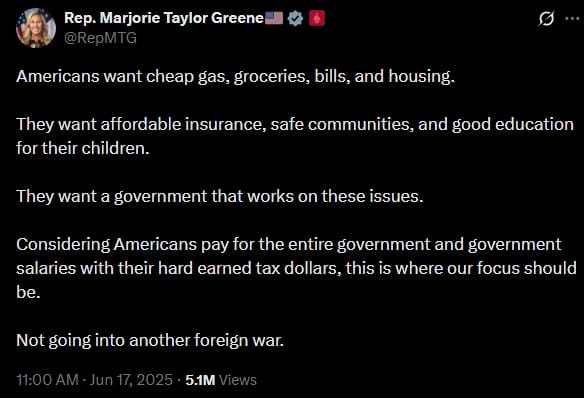

While no Republicans have signed on to the resolution yet, some Republicans -- including long-time Trump allies like Marjorie Taylor Greene -- have raised concerns that war with Iran would go against Trump’s promise to be a “no wars” and “peacemaker” president, especially as the White House says he will make a decision “within the next two weeks.”

Greene later added that there was no need to sign on to Massie’s resolution because the US had not yet attacked Iran.

During his inauguration, Trump promised to “build the strongest military in the world,” but added that success will be measured “not only in the battles we win, but also by the wars that we end and perhaps most importantly, the wars we never get into.” He added that he would be a “peacemaker and unifier” in his second term.

Many Republicans on Capitol Hill have already lined up to defend increased military presence and involvement in Iran. "Either you want them to have a nuclear weapon, or you don't. And if you don't, if diplomacy fails, you use force," said US Sen. Lindsey Graham, who has a track record of supporting military operations dating back to the 2002 Iraq War authorization.

There Is More to This Story Than Just Iran

The notion that Iran is close to a nuclear weapon has lingered in foreign policy discussions for more than a decade, but Massie’s war powers resolution and the alliance between polar opposite politicians who are willing to buck their own party (like AOC) go beyond one country and one conflict – especially since so many Americans still remember Iraq and Afghanistan.

In fact, the backdrop looks oddly similar. Graham and other defenders of Iran intervention say the country cannot be allowed to have a nuclear weapon and say it is close, though there is no hard evidence this is the case (especially since Iran has been weeks away for several years). It sounds like Iraq and the claims of weapons of mass destruction.

These claims ended up being false – but they helped bolster public support for invasion.

Then, there is the debate between defense hawks and non-interventionists and isolationists, which has sparked the biggest areas of political tension when it comes to military expansion in the Middle East and elsewhere. Case-in-point, former US Rep. Ron Paul’s 2010 speech on the House floor, condemning both sides for the US’s continued involvement in Iraq.

Perhaps the biggest area of contention is the issue of presidential war powers. Trump would not be acting in an unprecedented manner if he decided to order an attack on Iran. The debate over war powers goes back decades as presidents on both sides of the political aisle have adopted a position that it is better to ask forgiveness than permission.

Here are some notable historical examples:

- John F. Kennedy: The failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and naval blockade during the Cuban missile crisis both lacked formal congressional approval.

- Ronald Reagan: The 1983 invasion of Grenada was conducted without prior congressional approval.

- George H.W. Bush: The 1989 invasion of Panama to remove Manuel Noriega was launched without congressional approval.

- Bill Clinton: Airstrikes in Bosnia (1993) and Kosovo (1999) and cruise missile attacks in Sudan and Afghanistan (1998) did not first have congressional approval.

Many Americans may not know that Congress has not formally declared war on another country since WWII. The War in Afghanistan lasted nearly 20 years from Bush’s invasion on October 7, 2001, to Biden’ final withdrawal on August 30, 2021, and Congress never formally declared war, which Massie points out is power given to lawmakers in the US Constitution.

Article I, Section 8 states:

[The Congress shall have Power . . . ] To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water; . . .”

Still, whether it was prolonged and escalated engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan under Bush, continued war and drone strikes under Obama, or missile and drone strikes in Syria and Iraq under Trump, the party line in Congress has generally been to stick by the president or don’t look weak on foreign policy.

Figures like Ron Paul and Thomas Massie have stood out as outliers in Congress, arguing for the Legislative Branch to use the authority given to it by the Constitution when many of their colleagues wouldn’t out of fear of repercussions from party leaders. What’s more, Massie was willing to be the sole Republican to sign on to his resolution to prohibit Iran intervention.

Teaming up with high-profile Democratic lawmakers like AOC may seem odd through a partisan lens, but both lawmakers have something in common: They may not always be the most independent members of Congress, but they have shown a willingness to put principles and their voters’ interests first, even if it means condemning their own party for its actions.

And for that, their alliance is the most independent thing to happen in Congress and in the US political landscape this week.

Shawn Griffiths

Shawn Griffiths