Legislators Feel Caught in the Trap of Partisan Primaries

Editor's Note: This piece originally published on the American Enterprise Institute's blog and has been republished on IVN with permission from the author.

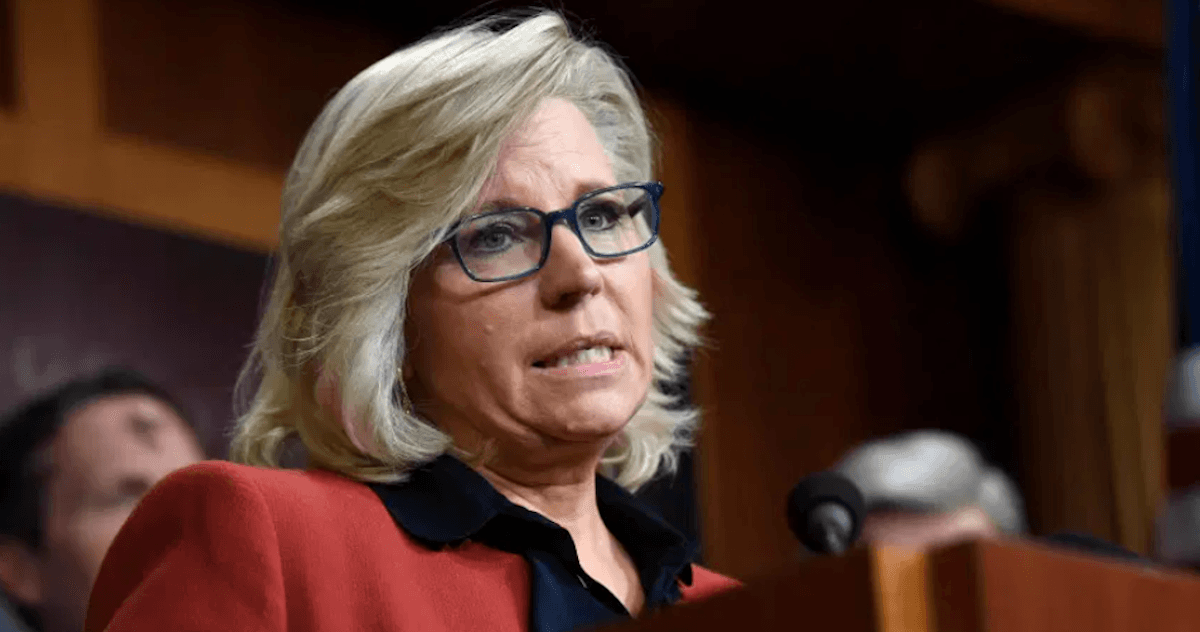

What is next for Donald Trump? There are reports that the former president is intending to play a role in the 2022 election. One report says his hit list includes Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY), Gov. Brian Kemp (R-GA), Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Rep. Tom Rice (R-SC).

Note: All of these individuals are Republicans. Rather than support opponents in the general elections against the Democrats who harried him, the former president wants to use the 2022 primaries to get back at legislators who were insufficiently obedient.

None of this should be surprising. One of the hallmarks of Trump’s presidency was his predilection for trying to exact retribution through primaries. During his presidency, he goaded #MAGA candidates to challenge senators and congressmen who dared to publicly disagree. Remember Arizona Senator Jeff Flake and Bob Corker? They are just two of the GOP legislators who crossed Trump and then chose not to run the primary reelection gauntlet. Most infamously, on January 6, Trump threatened to “primary the Hell” out of any legislator who refused to try to thwart the counting of states’ electoral slates.

That the electoral primary has become a weapon of an aggrieved former president is a remarkable development. But for those elections observers who have been complaining about primaries for the past couple decades, it likely is no surprise.

The partisan primary, wherein each party allows only its registered voters to participate, came into vogue a century ago. It was a progressive reform that toppled the old system that had Democratic and Republican party bosses picking their candidates. Letting party members pick their candidate was much more democratic and likely reduced some of the corruption that occurred in the proverbial smoke-filled backrooms. A recent report by the Open Primaries Education Fund notes:

“The American system of primary elections worked, because most Americans were members of one of the two major political parties and had access to them as a result of the overlap between voter and party registration. From 1940 to 1960, independent voters hovered between 15% and 20% of all registered voters. In 1961, 80% of Americans were members of either the Democrat or Republican parties.”

Reality, however, has moved on, and partisan primaries have developed into anti-democratic and elitist purity tests for candidates. Those who fail particular litmus tests on abortion, guns, or fealty to Donald Trump may find themselves defeated.

The causes are twofold.

First, many Americans have grown weary of the two parties. Today, 40 percent of Americans are independents, and in many states they are forbidden from voting in primary elections. The reader would be wrong to imagine this exclusionary policy was the province of the GOP. Both parties like closed primaries, which exist in red states like Kentucky and blue states like New York.

Second, astonishingly few voters participate in primaries. Typically, somewhere between 20 and 35 percent of those eligible to vote in the Democratic and Republican primaries do so. And these are not low-stakes races like local dog catcher — these abysmal participation rates are for congressional and presidential elections. The few who turnout naturally tend to be the most intensely partisan and single-issue voters.

The effects on Congress are plain for all to see. Legislators fear working across party lines on any issues that might tick off their most passionate voters. Republicans refuse to cut a deal on immigration that looks like “amnesty” and Democrats flee any talk of reigning in entitlements, which consume about 70 percent of the budget. Many legislators want to reach compromises on pressing issues like these, but they don’t. Nobody wants to get primaried.

There is, obviously, a way out. The parties could open their primaries to independents. Some states, such as West Virginia, have made this reform. Other states, like North Dakota, have open primaries that permit anyone to vote in the primaries.

In the meantime, the primaries trap draws tighter on GOP legislators, as Donald Trump plots his moves.

Kevin Kosar is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.