Beyond Ranked Choice Voting: How We Count The Votes Matters

Ranked choice voting keeps winning headlines. New York City uses it in primaries, Maine uses it statewide, Alaska uses it with a nonpartisan primary, and advocates from Better Choices are pushing for more consensus.

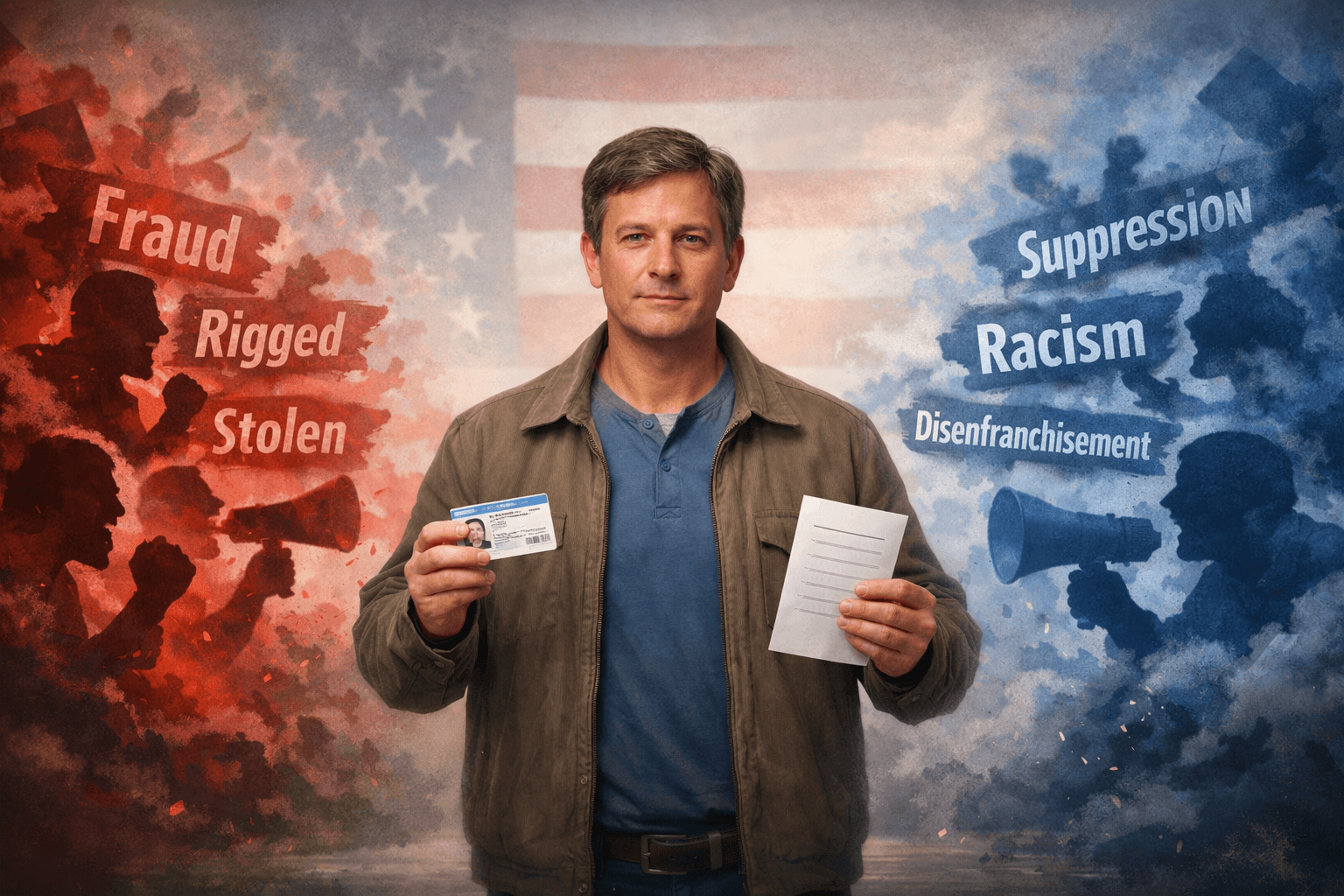

Nationally, Republicans voters tend to dislike ranked choice. Democrat voters tend to love it.

But underneath the headlines, election reformers understand that how you count ranked ballots matters as much or more than whether you let voters rank at all.

The Traditional System: Instant Runoff Voting Promotes More Viewpoints, but Can Also Penalize Moderate Candidates

Instant Runoff Voting (IRV), also known as the Alternative Vote, is currently the most commonly used ranked choice tabulation method in U.S. elections. Under IRV, voters rank candidates in order of preference. The counting process eliminates the lowest-ranked candidate in successive rounds, redistributing ballots based on the next available ranking until a candidate reaches a majority.

While IRV meets several common reform criteria, such as later-no-harm, it also introduces some vulnerabilities. For example, a candidate could theoretically be punished when a voter ranked them higher, rather than lower. Additionally, IRV does not guarantee the election of a candidate who could defeat every other in head-to-head comparisons, and in multi-candidate fields, vote exhaustion may result in ballots being discarded before the final round if no ranked candidates remain.

These characteristics shape the behavior of candidates and campaigns. Because IRV does not necessarily reward broad appeal, but rather surviving rounds of elimination, it can encourage segmentation. Candidates therefore, have more of an incentive to consolidate loyal bases of support, not necessarily to appeal across divides. In this way, IRV mirrors some of the factional incentives seen in traditional party primaries while offering voters more diverse choices than the common Democrat v. Republican contests.

Alternative Tabulation: Identifying Broadly Acceptable Winners with Consensus Voting

A candidate who would win a head-to-head election against every other candidate in a given election is called a “condorcet winner.”

Some reformers like Better Choices are building Condorcet logic into an electoral structure familiar to voters; ranked choice voting with a “consensus” method of tabulation. In these election systems, voters are asked to rank three or more candidates in a general election. The winner is the candidate who would defeat all other candidates if they faced each other head-to-head.

Simply put, this way of counting votes:

- Always elects a candidate who would defeat any other finalist head to head.

- Keeps ballot instructions simple for voters who want only to mark one choice.

- Ensures that ranking a candidate higher does not actually hurt that candidate’s chance of winning.

Most importantly, Condorcet-compatible systems alter campaign incentives. Candidates are rewarded for attracting broad second- and third-choice support. Theoretically (and practically?) the system should produce more moderation, collaboration, and bridge-building.

For a more academic discussion, election law professor Edward B. Foley uses a hypothetical Condorcet contest between Texas Senators John Cornyn and Ken Paxton to illustrate how traditional primary structures and binary runoffs can reward factionalism rather than consensus.

His argument reinforces a central theme of this article: the way we count votes changes the incentives. Condorcet-based systems don’t just tally preferences differently; they foster a fundamentally different theory of representation; one where the winner is the person who can unify a diverse electorate, not just mobilize a passionate segment of it.

In short, relative to proportional or IRV systems, Condorcet systems encourage campaigns to resolve differences with voters before taking office, rather than navigating entrenched factional divides afterward.

Proportional Representation: More Diversity of Viewpoint, Less Moderation

Some reformers see proportional representation, PR, as the gold standard of reform. That perspective embraces a more parliamentary perspective on governance: one where representatives are champions of their segment and fight for their viewpoint inside the government itself.

Proportional Representation systems deliberately divide seats in government bodies by faction. That model works in parliamentary democracies where parties negotiate coalitions after the election, as advocated for by organizations like Protect Democracy, FairVote, and the ProRep Coalition.

Candidates in proportional representative systems, therefore, are incentivized to campaign to their base, and negotiate their power with other factions after the election.

Therefore, a natural consequence of a proportional representation system is representation of more differences: whether by ideology, race, gender, or anything else. The point is, the more there are differences, the more a faction can fight for a seat at the governing table.

This is a legitimate theory of governance, but different from a system that seeks a government of more moderation.

These differences highlight a foundational distinction: PR tends to reward a more tribal identity. Condorcet systems reward coalition-building. One resolves disagreements inside the government apparatus, while consensus reforms attempt to have differences resolved by the electorate.

The National Conversation about Ranked Choice Voting is Oversimplified

The national conversation over “ranked choice voting” is not about a single reform or perspective as many media outlets and political commentators suggest. Advocates of reforms that give voters more choices, among themselves, have different perspectives, long-term agendas, and priorities.

When voters, or coalitions, organize around a given counting method, we often trade one set of voter frustrations for another. Sometimes, that reform, as in New York City, is the result of a compromise between reformers and the people in power; offering the IRV form of ranked choice voting only in closed primary elections, for example.

So, when considering ranked choice voting, it’s worth asking yourself: Do we need more perspectives, or more consensus, in government?

Either answer can lead you to ranked choice voting.

So why do so many people argue over “the right answer” for democracy?

Frankly, because there may not even be a right answer.

Chad Peace

Chad Peace