How to End Partisan Gerrymandering for Good -- Using Simple Math

Sam Wang has used a combination of computer simulations and simple math tests to help reveal the partisan intent behind the post-2010 redistricting. All this work gave the neuroscientist a new obsession with political reform, electoral fairness, and ending the gerrymander once and for all. What started has a hobby evolved into award-winning tests to uncover partisan gerrymandering, influential law review work, and now the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. His latest op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, co-written with Brian Remlinger, holds out hope that math can save our democracy. We checked in with him for a few additional questions.

Your op-ed poses a provocative question. So, do you think that math can solve partisan gerrymandering -- and if so, what is the best mathematical approach?

Math (without maps) can be a tool to help with diagnosis. It's not really so fancy: math can be used as a measurement tool, the way one would use a scale or a cup in the kitchen. Math can come up with a simple measure of whether the two major parties are treated differently.

Of the many mathematical tools, I am interested in finding one that has the longest history. I have lately been emphasizing the t-test, which was invented almost 100 years ago by William Gosset, experimental brewer for the Guinness Brewing Company. He was trying to do quality control on hops, and he developed what is now the most widely used statistical test in all of science. He published it under the pseudonym "Student." To this day that's what it's called – Student's t-test.

Can you explain your Monte Carlo approach? How might that reveal the hand of partisan gerrymandering?

Monte Carlo sampling is just a form of finding out what would happen by chance, by making random picks. For instance, if you wanted to test whether a coin was fair, you could flip it a bunch of times and see how often it came up heads. A fair coin comes up heads half the time. If the actual number of heads is far enough from half, then we conclude that it could not be fair.

In the case of districting, Monte Carlo sampling is done by picking a bunch of districts from around the country, in a number equal to the number of districts in a state that you are investigating. Then, accommodations that match the states actual vote, count the number of seats for each party. Such an approach gives us a feeling for how accepted districting procedures around the country play out, when applied at random.

There have been many more complicated mathematical tools suggested to combat gerrymandering lately. Are you suggesting that there's an easier way to show this? Might the more complicated approaches confuse the matter in important upcoming gerrymandering litigation?

The more complex the standard, the more ways there are to poke holes in it. Even if the test doesn't seem so complicated, if it's based on a new idea then that opens the possibility of criticism. That said, complex standards have an important role in quantifying specific concepts. For example, a researcher might like to know how many votes are wasted.

The t-test has the advantage of extreme simplicity: are one party's wins more lopsided than the other party's? That's what the offense of packing and cracking accomplishes directly. Without it, partisan gerrymandering is not possible.

It may be helpful to have more than one test because individual states sometimes have quirks that need to be analyzed a little bit differently. So we are looking at other tests as well.

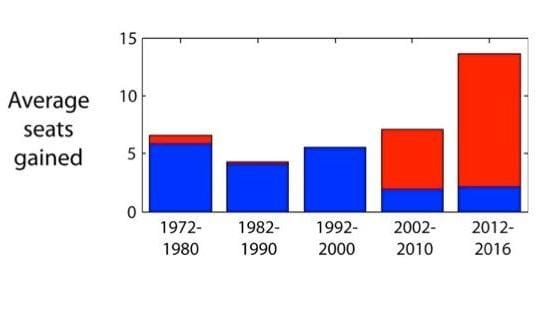

A graphic with your op-ed that you created shows that the number of House seats gained by partisan gerrymandering doubled between the 2000 and 2010 redistricting cycles. How do you prove that? And why do you believe this is partisan gerrymandering and not natural sorting?

That graph is the result of the Monte Carlo simulation. It represents the net gain in all states where one party appears to have arranged an advantage for itself.

One big tell for a partisan gerrymander is that the size of the advantage changes suddenly when the party in control changes. This happened in North Carolina in 2010, when partisan control switched from Democratic to Republican. Populations of voters didn't move – the boundaries moved around them.

In a discussion on your website this week, you noted that "partisan gerrymandering is made possible by having many districts," and that "the more boundaries there are, the easier it is to commit bad acts." Districting itself is the problem. What if we adopted multi-member districts: Fewer districts for politicians to manipulate, more choices for voters.

That could work. You would need at least five members per district to give power to both parties.

However, I believe that under current national law, congressional districts must be single-member. At state and local levels, my understanding is that multimember districts have been used in the past to suppress minority representation. Any reform would have to be constructed to avoid repeating that offense.

Editor's note: This interview originally published on FairVote's blog. To learn more about FairVote, visit the group's website, or follow them on Facebook or Twitter.