Maine’s Ranked Choice Voting: Not Perfect, But A Step Up from Plurality

Measure 5 puts ranked choice voting (RCV) on the ballot to be used statewide. RCV is worthwhile to support because it’s better than Maine’s current plurality voting system. But if you dress up RCV and say it can do things that it can’t, then you’ll set yourself up for disappointment. And that false praise may very well set up Maine to add itself to the list of places that have repealed RCV. We’d rather not see that downslide, so this article is to prepare you.

Believe it or not, this is a pro RCV piece. At the end of the day, you have to remember that Maine’s Measure 5 is to choose between plurality and RCV. Plurality’s awful performance as a voting method puts the bar very low, so low that even a mediocre voting method like RCV is better.

What Is Ranked Choice Voting?

In case you’ve gotten this far and you’re not sure how RCV actually works, here’s a primer.

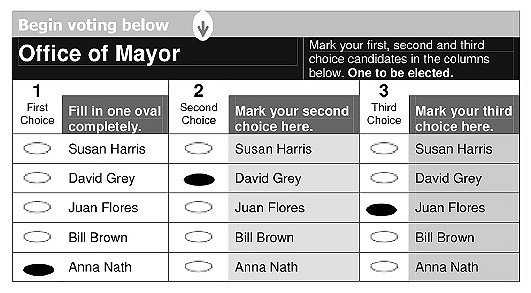

To start, you rank your top three choices and turn in your ballot. Then the magic happens.

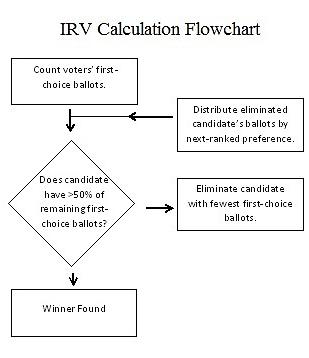

Now, your first-choice votes on all the ballots are counted. Is that more than half of the valid votes? If yes, you’ve got yourself a winner—likely the same winner you would have had under plurality voting, in which the voting method wouldn’t have mattered anyway.

This time, however, let’s say you add up the first-choice votes and there’s no candidate with more than half. Now you take the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes, eliminate that candidate, and look at those ballots’ next-choice vote. You take that next-choice vote and transfer those ballots as if they’re now a first-choice. And you ask yourself again if any candidate has more than half of the votes. If so, you have a winner. If not, you keep repeating the process until someone has more than half.

As a heads up, the “more than half” is referring to the active ballots, not the original ballots. Ballots may be exhausted either by people ranking fewer than three candidates, or RCV may take the election over so many rounds as to go past voters’ allowable rankings.

To clarify, you may hear RCV called by other names such as instant runoff voting, alternative vote, plurality with elimination (not runoff), and Hare. They’re all the same thing. But RCV is not the same as single transferrable vote or choice voting. That’s a multi-winner proportional method, which behaves differently and has different properties.

Plurality Voting Is Really Bad

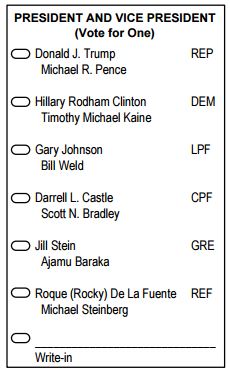

Let’s talk about Maine’s current system, plurality voting. That’s the one where you select one candidate and the candidate with the most votes wins. It’s very simple. And that’s the only advantage it has over ranked choice voting. We even wrote out a whole article listing why plurality voting is so awful.

We often cite Voting Powers and Procedures, a group of voting theory experts out of the London School of Economics. When they did an internal vote on voting methods (very meta, I know), not a single expert gave plurality voting any votes. It came in last with zero.

Maine’s current plurality voting is the worst at supporting races with more than two candidates because of its sensitivity to vote splitting.

Vote splitting just means that similar candidates can divide their vote when voters are limited to choose just one of them. Candidates who are more distinct (either in a good or bad way) are more likely to keep all their support.

Plurality voting is so sensitive to it that even a fringe candidate taking away just a few votes can change the outcome in a close election. And that’s no good. That’s because it can change the winner to a candidate who is highly disliked.

RCV Is Technically Better Than Plurality Because It Mitigates the Spoiler Effect

So you’ve got that crazy scenario in your head where candidates with little support (spoilers) can turn the election? RCV likely fixes that specific scenario.

RCV would eliminate the candidate with little support and the voters who supported that candidate would get their ballot transferred to the next-preferred candidate. That would address the issue.

That benefit alone is enough to make RCV better than plurality voting. We were serious about plurality voting creating a low bar!

Two False RCV Supportive Claims

Unfortunately, many of the claims for RCV go well beyond what’s merited.

1. “With ranked choice voting, you have the freedom to vote for the candidate you like the best without worrying that you will help elect the candidate you like the least.” - Yes On 5 (False)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rkx0e2Cduyk

As much as proponents want this to be true, this is false. This is shown not just theoretically, but in actual elections.

Because of RCV’s complexity, this is difficult to explain, so we made a video on it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JtKAScORevQ

Plus, this issue came up in Burlington, VT. Conservative voters got their least favorite outcome by ranking their honest favorite as first.

A common reply to this criticism is that all that strategy is complicated to follow—and for those not used to thinking about this, it really is complex. But whether you can follow the strategies doesn’t matter because voters can get hurt either way.

If you’re unfamiliar with the issue or can’t work out the complexities, you may vote for your honest favorite. But that won’t change the fact that voting your favorite can still produce that bad outcome you’re fearing.

And if you’re familiar with the issue and you do vote tactically by ranking a compromise first, then your behavior looks more like what we’d see under plurality voting anyway.

2. “The fundamental issue is majority rule. Without a majority standard, you can’t hold the powerful accountable.” - Former Vermont Governor Howard Dean (False)

Very often, you hear the claim that RCV ensures majority rule. That is, that you’ll always end up with a winner who has more than half the votes. The truth is that no voting method can guarantee an (absolute) majority when there are more than two candidates. That’s because that majority candidate doesn’t always exist, and typically there is no majority winner in competitive races with more than two candidates.

To be fair, RCV will pick the majority winner when that candidate exists. But so does plurality voting, meaning there’s nothing much to be gained by that claim.

RCV appears to arrive at a majority winner every time, but it really doesn’t. As ballots are exhausted over rounds and you’re checking for that majority, you’re looking at the ballots remaining—not the ballots you started with. And so the ballots you’re looking at in the end could be only a fraction from where you began. This makes that “majority” merely contrived.

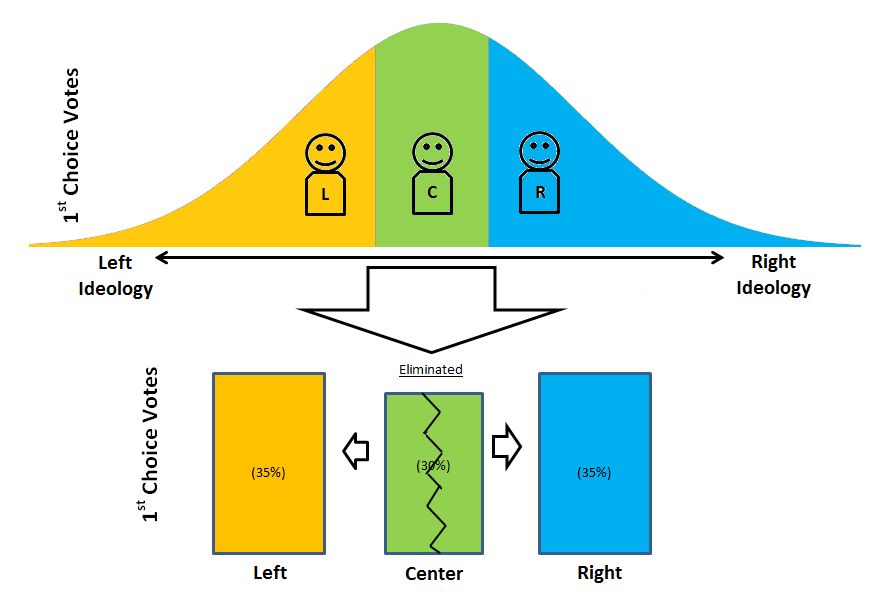

RCV also gives this majority appearance by narrowing the candidates down to two. But that’s rather arbitrary because of course you’ll get a majority if you can narrow the field to two. That doesn’t mean, however, that you’ve eliminated the correct people. RCV’s vote splitting of first-choice preferences can wrongly eliminate good candidates.

A more useful—though still imperfect—concept of majority is having a candidate who can beat everyone else one-on-one. This is called a “Condorcet” winner. The catch is that this Condorcet winner doesn’t always exist either. And RCV can even overlook a Condorcet winner when one is present (though not as easily as plurality voting would).

Here’s an example of how RCV’s version of vote splitting can eliminate a good candidate (here, the moderate candidate) who is also a Condorcet winner. This phenomenon is known as the “center squeeze” effect due to the vote splitting occurring on both sides of the moderate candidate, squeezing that candidate out.

This isn’t to say we haven’t been surprised. For instance, Maine’s 2014 Gubernatorial election had a tight three-way race. We were able to do exit polling with volunteers and reweighted the ballots according to the plurality ballots in proportion to what was seen in the official results. There, RCV managed to produce an objectively good result—although just barely. This could be because the moderate candidate in that election was able to stand out on multiple issues.

Two False RCV Oppositional Claims

1. “I feel uncomfortable passing a bill to the voter that we know is unconstitutional — especially without disclosing that fact — in an effort to fix it after the fact.” - Rep. Heather Sirocki (False or fixable)

There are two constitutions to keep in mind here: US and State. On the US Constitution, there’s the idea of “one person, one vote”, enshrined from cases Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims. These cases dealt with the weight of people’s vote caused by districts with largely disparate population sizes. RCV treats everyone’s vote with equal weight, so this isn’t an issue.

On the state constitution side, there are two issues, which are highlighted well in a letter by Janet Mills, Maine’s attorney general. The issues are whether either of these requirements constitutionally bar RCV: (1) Maine’s mandate for a plurality and not a majority winner or (2) the requirement for precinct tabulation.

As mentioned before, RCV—like all voting methods—cannot guarantee a majority winner. The idea of majority is strange within the context of voting theory. That Maine’s constitution requires a plurality winner is not necessarily prohibitive. We have to understand intent, and it could be that the intent was to have a winner who was at least the plurality winner. And many different voting methods arrive at a winner by a plurality of the vote, but because each voting method has its own process, that winner may be different. So this mention of plurality isn’t necessarily a requirement to use a particular voting method.

The other part that comes up is that the voting method must be computed within each municipality. That’s tough for RCV because calculating its results requires that all its ballots be at the same location. It’s not precinct summable. Precinct summable means that you can take the totals from all the precincts to get a result.

The workaround here could be that the municipality records all the ballot data and then transfers that data to a central location. And indeed, this data should be publicly available and verifiable anyway. The Maine constitution's insistence on a municipal count may have been a check to uphold that verifiability. You always want raw voting data to be publicly available and have strong chain of custody procedures, and this is still possible with RCV at the state level.

So there is more constitutional friction with Maine’s constitution than the US’s. Part of this depends on the reading. (Yes on 5 predictably has experts providing some favorable reading.) A clarification with a clearer and broader writing of Maine’s constitution may actually be beneficial. And it looks like that kind of clarification—if needed—is something Maine’s legislature is capable of providing.

2. “Ranked choice voting would further disenfranchise voters by using the recounted ballots of the loser to determine the winner ”- Rep. Heather Sirocki (False)

Rep. Sirocki’s premise is that your ballot shouldn’t influence the outcome unless you supported the plurality voting winner. Rep Sirocki is in a field to herself in her endorsement of plurality voting. Keep in mind that every other single-winner voting method uses more information than plurality voting.

To say that voters shouldn’t be able to either contribute that information or have it counted is to bar voters from ever using a meaningful voting method. Rep Sirocki has also (wittingly or unwittingly) opposed runoffs with her statement. Not that that’s a good solution either.

RCV Can Move Voting Methods Forward

Maine would be wise to ditch its plurality voting system. And this would be exciting because this is the first case of an alternative voting method besides a runoff being used at the state level to this extent. The sooner Maine can be rid of plurality the better.

Just be mindful of what you’re getting. RCV is a moderately complicated single-winner voting method. Some of its criticisms are justifiable, such as requiring expensive software. And RCV can experience some strange anomalies, particularly when more candidates run. To be fair, all voting methods have some kind of quirk to them, though to varying frequencies and degrees.

If you want to think about it another way, imagine each voting method as a job candidate. You want to hire the best one. RCV is roughly your C-hire—a mixed record that carries some baggage. Plurality voting is a solid F-hire with a long list of terrible references. Between those two, you go with the low-performing hire over the F hire. Easy decision.

Of course, if you had the option, it would be nice to pick out an A-hire (*ahem* approval voting) that is less complicated and solidly better than the C-hire. But unfortunately approval voting is not on Maine’s ballot.

So long as Maine appreciates that RCV is a mediocre approach that at least moves away from the worst voting method there is, then they shouldn’t be too disappointed.

Editor's Note: This article originally published on the Center for Election Science's blog and has been modified slightly for publication on IVN. View the original article here.