The Facts versus the Myths about Our Flag, and how they relate to commerce and politics

Friday, June 14th 2013 was flag day, a day which tends to go uncelebrated, and about which most people know very little.

This post will be a brief detour from my continuing series on the different facets of the Kiera Wilmot Bottle Bomb story.

It looks long, and it is, but most of it is pictures. As you look through the various images included here, I hope you will contrast the actual origins of the U.S. flag, as it was originally adopted by the Founding Fathers, and contrast that with the nice little folk story about Betsy Ross.

While it is true that Ms. Ross was commissioned to sew a flag for the new entity we call the United States of America, it is NOT true that her design was very original, as you will see below. Our flag is in reality, a reworking of the official flag of the East India Company, which I think puts an interesting cast on the role of corporate involvement in both our government and our history. This is particularly intriguing, in respect to the Boston Tea Party, which was a protest equally against British taxation AND the monopoly of the East India Corporation regarding tea and other items that were important to consumers, and on which the East India Company made huge profits because of that monopoly arrangement with the British government that they exploited so greatly to their advantage.

This raises the inevitable question, was this the most patriotic and best choice for a new nation, seeking to separate and distinguish itself clearly and unmistakably from other entities, either corporate or national? In my research into these flag designs, I have yet to discern an adequate explanation for this choice that really makes sense in terms of a symbol representing our national identity.

Also, contrary to the folk myths, there were both more people and more alternatives involved in the flag choices than the one submitted by Betsy Ross in the traditional version of events involving her and George Washington.

I like the history of our holidays, major and minor. So in honor of our flag and Flag Day, here is a brief description and history of our holiday. Flag Day celebrates the adoption of a national flag at the Second Continental Congress on June 14, 1777.Here is the beautifully brief wording:

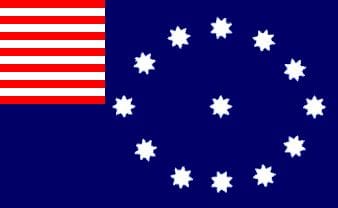

Flag Act of 1777Second Continental CongressFlag DayUnited StatesJournals of the Continental Congress, 1774 – 1789So, you would think that settled the design of our national flag, except that the concept of a national flag as we know it now didn't really exist in the 18th century; it was a later development.Credit should go to both Wikipedia for some of these images, and to an excellent site, Flag Timeline of USHistory.org for many of the others.What the Flag Act resulted in were a number of designs which conformed to that brief wording, including but not only the Betsy Ross flag - although the Betsy Ross flag eventually won the greater recognition. Here are some of those flags used at the time:The Second Continental Congress started out meeting in Philadephia, but then later in the year moved around Pennsylvania to other locations, including Lancaster and York. The national flag came into existence two years to the day of the official establishment of the Continental Army in 1775.However there WAS a flag that was flown as early as 1775 by our newly formed Navy, referred to as the Continental Colors. It differed from the East India Flag ONLY in the proportions of the Canton. (The 'canton' is an heraldic term, referring to the little box in the upper corner).

American War for IndependenceContinental CongressnavyRed EnsignAlfredJohn Paul JonesensignRed EnsignsAlfredMargaret MannyAnd here is a short bio on Margaret Manny, who is less well known than Betsy Ross, but who was both earlier, and equally influential in our final flag.

PhiladelphiaUnited StatesAmerican Revolutionjacksensigns1774Grand Union FlagJohn Paul JonesAlfredMy thanks to my friend Laci for calling my attention to rich history of the East India Company flag, which preceded our own flag by a full seventy years, as a very British and a very corporate flag, first used in Asia. The East India Company flag stripes were somewhat 'variable' in number, ranging from nine to fifteen which mirrored our own experimentation with stripe numbers. The symbol in the upper left corner, in the 'Canton' division, also changed over time, representing changes in the UK. We didn't pioneer that pattern of alteration to reflect growth and change either.And there was one other variation, the Easton flag, on the pattern of the East India Company flag - reversing the canton and the larger field stars and stripes. This is a flag that was used for a company of Pennsylvania soldiers in the war of 1812, from Easton PA:

But the adaptation of the flag of the East India Company, while strikingly similar is not the only theory for the design adopted by the Continental Congress.Another theory is based on the family coat of arms of Richard Amerike:"According to the American Flag Research Center in Massachusetts the heraldic origin of the American flag is not positively known; archives in the British Library confirm that the Stars and Stripes was the coat of arms of the Ap Merike family – and that they pre-date Washington's connection with the continent by 300 years".The coat of Arms belonging to the family of George Washington has three stars in chief (at the top) on a white field, with two red horizontal stripes across the middle of the escutcheon, underneath it. The Amerke basis for the flag is generally considered 'revisionist history'. Clearly neither coat of arms are as similar as the East India Company flag design, but both provide some insight into the heraldic tradition that was the foundation for flag design.From Wikipedia:

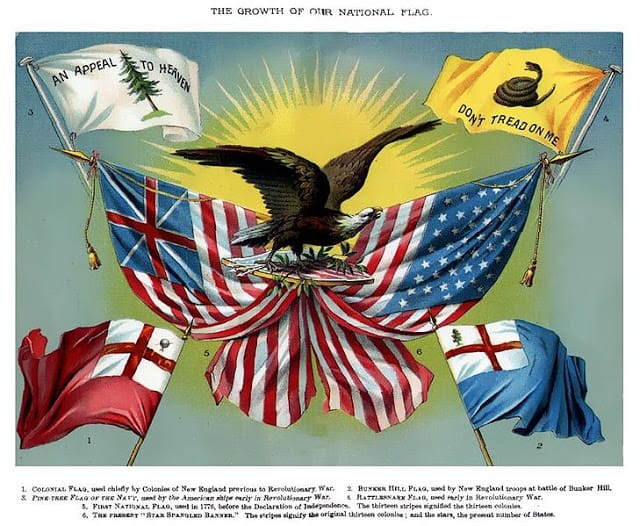

stripes (barry)stars (mullets)Valaisseven districtsThe thirteen original colonies were the basis for thirteen stripes and the thirteen original stars on the first official U.S. flag, but in the Flag Act of 1794, that was temporarily expanded to fifteen stripes and stars with the admission of the first two new states. Had that pattern continued, our flag would now have 50 stripes along with the 50 stars.It is a fascinating insight into how the flag has changed, but also into how the nation under George Washington thought about our national expansion at the time. It wasn't until the Flag Act of 1818 that the stripes were codified as representing the original 13 colonies, with the stars changing -- with such changeovers always mandated to occur on July 4th -- to represent the number of states at any time in our nation with only the stars.Here is the order of the states joining, representing each of those stars, because of course there was no official membership or ratification until AFTER the sessions of the Continental Congress:Delaware (December 7, 1787), Pennsylvania (December 12, 1787), New Jersey (December 18, 1787), Georgia (January 2, 1788), Connecticut (January 9, 1788), Massachusetts (February 6, 1788), Maryland (April 28, 1788), South Carolina (May 23, 1788), New Hampshire (June 21, 1788), Virginia (June 25, 1788), New York (July 26, 1788), North Carolina (November 21, 1789), and Rhode Island (May 29, 1790) (source - Flag Timeline)This is a singularly striking image from th 1880s that shows some of the various permutations of our flag over the years, from an old textbook (courtesy of wikipedia):