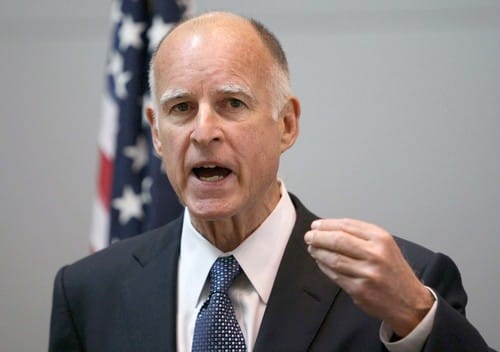

Why Jerry Brown can't be underestimated

There’s no doubt that when it comes to the Gubernatorial race, former Governor, Democratic nominee and California political icon Jerry Brown is in a tough fight. His opponent is deep-pocketed, ideologically flexible, savvy and has the appearance of uniqueness. She has huge segments of the press on her side, the narrative solidly in the bag and is busy remaking her own state party into a juggernaut that can bankroll not just her race, but every other race in the State. Against such a force of nature, any politician would rightfully quail.

There’s just one problem – despite all these advantages, Meg Whitman can’t seem to crack a single digit lead. And in an election cycle where Republican candidates like Ohio’s John Kasich are leading by as much as 20 points despite being at a fundraising disadvantage, that’s a warning sign for a candidate who’s spent over $100 million of her own money. To be sure, Meg Whitman is powerful, and to this point, Brown has shown lackluster signs of life in his battle with her. However, Brown still has a chance, and to count him out would be absurd. He didn’t get this level of recognition by being a fool, and the fact is that the Brown campaign’s advantages – namely, alliances and expectations – are just strong enough to keep him solidly in the game.

First, there’s the question of alliances. While Meg Whitman no doubt has oodles of money to throw around in her attempt to defeat Brown, there’s one very significant thing to note about that money – it’s all her own. This means that whatever Whitman spends on ads, door-to-doors and events, it will all be money spent to prove to people that they should support her, rather than money that is spent as evidence that people do support her (which is what most candidates with fundraising advantages can claim). By contrast, Jerry Brown has several deep-pocketed allies in the public and private sector unions, whose money and virulent disgust with Meg Whitman will continue to keep him competitive, even if his own campaign runs on a shoestring. This sort of power also enables Brown to outsource all his negative advertising to other groups, effectively giving him license to run as a positive candidate (which is what this election cycle seems to be demanding). This in contrast with Whitman, whose entire operation is bankrolled with her money, and thus comes back to her in peoples’ minds.

Second, there’s expectations. Meg Whitman, whatever her advantages, is practically required to maintain a lead, given that anything else will look like the most titanic waste of money since…well, the Titanic itself. This means that if Brown shows himself to be viable, it complicates the press narrative of a Whitman juggernaut and enables him to draw attention to Whitman’s copious amounts of campaign cash as a basic argument about fairness which (rightly or wrongly) voters are likely to find sympathetic. Brown’s “fighting liberal” image is well-suited to an underdog role, as evinced by the barely furnished campaign office he runs out of. The disproportionate expectations Meg Whitman must meet thus work to Brown’s advantage, especially at the point where he can sell himself to a state that has made a habit of electing him, and whose political orientation lines up far more neatly with his own than with the Thatcheresque, barely authentic self-funder he faces on the other side.

In short, Brown has the materials and arguments necessary to win in a fair contest. Sadly, he has failed to utilize them during his campaign up to this point. However, there is absolutely no reason why Whitman should find complacency to be an attractive option. Jerry Brown has been elected before, and Jerry Brown could very well get elected again.