The Wedging of America: How Party-Focused Elections Suppress The Real Majority

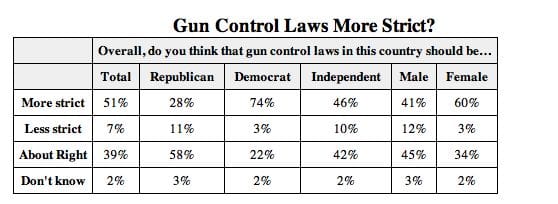

The United States is made up of about 1/3 moderates and has more Independents than any other party affiliation.

Even within the Republican and Democratic parties, and among liberals and conservatives, there is a wide spectrum of policy opinions on issues ranging from economics to abortion. It may seem obvious that Americans’ multifaceted and surprisingly centrist perspectives aren’t reflected in party candidates, but there is more afoot here.

Common sense might suggest to us that the need to win elections would drive politicians to fight for that 43%+ Independents and thus “run for the middle.” There is, in fact, a significant amount of literature from the academic world in the 2nd half of the 20th century that suggested that the US’ two-party system was problematic because it would not provide any choice: both parties would “run to the center” and we’d essentially be picking between two equal, centrist options.

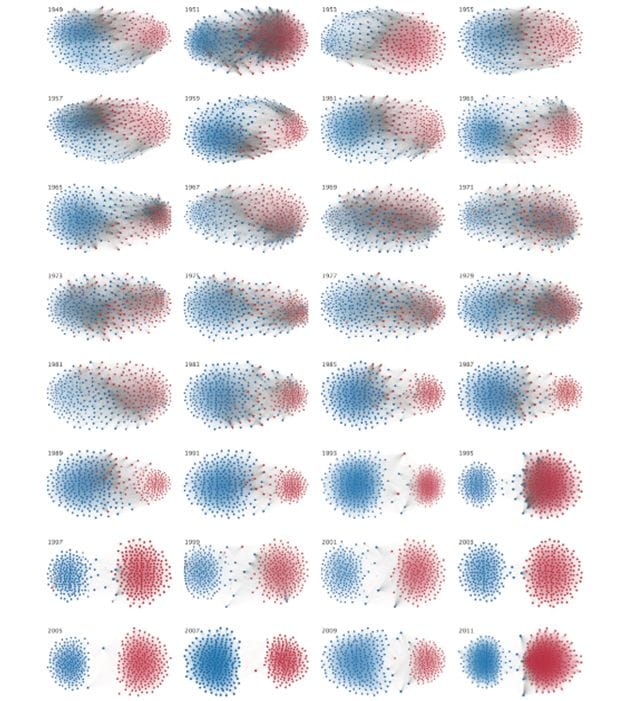

We know now that this doesn’t happen--in fact, Republicans and Democrats in Congress are becoming hyper-polarized, voting against each other in nearly every bill that comes across their desks.

It seems laughable in retrospect, but it certainly does seem to make sense. Why on earth doesn’t this happen?

The short answer is “political incentives,” and it comes in two phases: the primary and the general election.

Incentives in the primary are a problem we’re already aware of. Candidates have to “run to the extremes” to pick up the hardcore base that votes reliably, donates lots of money, and is highly socially influential. If we look at who’s surgeing in the presidential primaries right now, it’s no surprise.So primaries bias the general election to have more extreme candidates. As voters flee the increasingly-polarized parties to be Independents, the most partisan are left behind to decide who goes on to the general election.

Then candidates have to try to pivot after winning the primary to win the general. As the 2012 Mitt Romney campaign’s infamous “etch-a-sketch” gaffe illustrates, a candidate has to try to reinvent oneself, at least a bit, in order to start going after those Independents. This is difficult. But simply modeling the process this way misses a critical factor in the political calculation of a candidate: voting likelihood.

Consistent conservatives and liberals vote far more often than less-partisan Americans. In mid-terms, where only 36% of voters turned out in 2014, the gap between Independents and party-affiliated voters grows.

It turns out it’s hard to get undecided people to turn out for an election. Politicians seeking to win with limited resources make a simple calculation: is the return on investment higher if I try to maximize turnout from my base, or try to win over a group that has low turnout and is unreliable (in that they might just vote for the other guy anyway)? Turns out the first strategy works best. So in many elections, candidates simply calculate that they don’t need to appeal to the center to win.

So this gives us the situation we see today: Congress is full of people that represent a shrinking partisan minority on either side. It also explains why the US seems entirely divided into two ideological camps: politicians that have calculated to rely only on left-wing or right-wing votes talk only about the issues in a way that is most likely to rouse the party base into voting.

And because we usually only hear politicians--and the media that discuss them--talking to these political camps, it’s easy for an outsider to imagine that centrists simply don’t exist in the US at all.

Finally, the saturation of extreme rhetoric habituates Americans into making a false choice between two partisan sides on an issue. The bitter vitriol and division we see in Congress reaches our day-to-day conversations even though our policy differences remain diverse. Having to choose between “pro gun control” and “pro gun freedom” rather than discussing details in policy where we have broad agreement, causes American political discourse to break down.

This is a process we call “wedging:” politicians engage in tactics that are politically profitable but ultimately drive Congress and more partisan voters toward edges that can no longer work together. In this process, the center--which once served as a moderating force--is shut out of the political process and suppressed entirely.

Editor's note: This article originally published on The Centrist Project's blog and may have been modified slightly for publication on IVN.