Why a Federal Commitment to Education Matters

“Before any great things are accomplished, a memorable change must be made in the system of education and knowledge must become so general as to raise the lower ranks of society nearer to the higher. The education of a nation instead of being confined to a few schools and universities for the instruction of the few, must become the national care and expense for the formation of the many.”—John Adams

Let's at least be clear about what happened Tuesday: a razor slim majority of the US Senate approved handing over public education in this country to a person who does not support the IDEA of public education in this country, or the IDEA that education is a public good (that everyone benefits from when it is widely available) as opposed to a private commodity (that should be available only to those who can afford to pay for it).

On the same day, a group of congressional representatives introduced a bill to abolish the Department of Education altogether, arguing that education was not a federal government responsibility and that "education of our students should lie primarily with parents, teachers, and state and local officials who know how to meet their individual needs best." It is hard to look at these two events and not come to the conclusion that public education at the national level is seriously under attack.

Now Rome didn't fall in a day, and there is a very entrenched educational apparatus that will be difficult to dismantle in four years. But still, ideas matter. And the idea that the federal government should take the lead in making education available to the entire nation is an idea that goes back to America’s founding.

America’s Founding Fathers were not the sort of men who agreed about much. They all agreed, though, that America should not be governed by the British. And, they also agreed that we should not create the same kind of society that existed in Great Britain. In practice, this means they disdained the political institution of monarchy (the hereditary transfer of power) and the social institution of aristocracy (the hereditary transfer of privilege).

Their distaste for aristocracy, more than any other factor, explains their near universal support for education and their general agreement with John Adams’ belief that education, including higher education, “must become the national care and expense for the formation of the many.” Education was then, as it is now, the most powerful social equalizer.

Without broad access to education, they knew, America would risk becoming a de facto version of the highly stratified nations of Europe, where wealthy families ensured that their children — and nobody else’s — would control most of the next generation’s wealth.

And this is what is at stake in the unprecedented debates that have been occurring about the nomination of Ms. DeVos to head the education department. From where I sit, the most important thing that the Department of Education does ensure something like equal (and, one may hope universal) access to education. Any debate that focuses on the local control of curriculum is going to be a red herring. Public school curricula have always been under control of local and state governments. The debate we are having now is about who pays for stuff, and, to a great extent, it is about who pays for higher education.

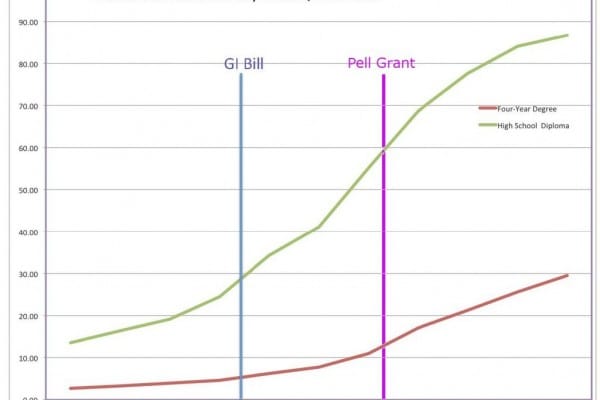

One of the great accomplishments of the United States in the 20th century was the raising of the college graduation rate from about 3% when the century began to around 25% when it ended. As a result, at the end of the 20th century, the United States had the finest higher education system in the world. This was not, however, due to steady or consistent growth over time. It was the result of two very specific federal programs that did exactly what they were designed to do:

The growth of public higher education in this country—and with it the unparalleled economic growth of the US economy in the 20th century, can be attributed, to a very great extent, to the G.I. Bill and the Pell Grant program. With the possible exception of the US Interstate Highway system, these are the most significant, and most successful initiatives, public or private, that anyone in this country has ever managed. For most of the 20th century, higher education was treated as a public good, and, as a result, the entire country flourished.

But the job isn’t over yet. We have a long way to go. College graduation rates have stalled out at 25%, which seriously jeopardizes our ability to compete in the new global economy. Without a major initiative to improve these rates—and the federal government is the only entity that has ever successfully done this in the past—the United States will soon cede its role as a leader in education, science, and technology.

At the same time, college costs continue to spiral upwards at a time when the income disparity between the richest and poorest Americans is at its highest point in nearly a hundred years. Access to education is the best way that we have to reverse this trend. And if the trend is not reversed, we will soon become precisely the nation of self-perpetuating aristocrats that we were founded not to be.

This is a very, very bad time to go backwards on our nation's commitment to public education.