How State, Federal Courts Are Working to End Partisan Gerrymandering

Florida's Supreme Court struck down much of the state's congressional districting map on July 9, ordering the redrawing of what it termed "constitutionally invalid" districts in 2 of the 27 districts (requiring a change to 8 congressional districts). Each district represents about 710,000 voters, making this one of the most significant court cases ever involving the practice of gerrymandering.

In 2010, Florida's voters overwhelmingly approved (62.9%) a constitutional amendment with some of the sternest requirements for the drawing of congressional districts:

Congressional districts or districting plans may not be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or political party. Districts shall not be drawn to deny racial or language minorities the equal opportunity to participate in the political process and elect representatives of their choice. Districts must be contiguous. Unless otherwise required, districts must be compact, as equal in population as feasible, and where feasible must make use of existing city, county and geographical boundaries. Florida Amendment 6 ballot summary, 2010

This amendment was immediately challenged in the courts, and was eventually upheld in federal appellate court by a unanimous decision in 2012.

Two years later, the state districts were still not in compliance with the amendment's directives, with 51 percent of the electorate able to capture over 60 percent of the legislative seats in 2014.Gerrymandering has been with us since the very beginning of the Republic, when Founding Father and former-vice president Elbridge Gerry attempted to skew election results as governor of Massachusetts.

In 1812, the Boston Gazette immortalized the term, by suggesting that Gerry's new districts looked like and had the same dangers of a mythical creature, the 'gerrymander,' complete with claws, fangs, and wings.

It's absurd to think that politicians could resist the temptation to commit gerrymandering, but this mythical creature still has a nasty bite--and that's when the courts have to have the final say in the matter.

Fair, Equitable, and Rigged: Subtle Differences Have Big Impacts

When our government was founded, having regional congressional districts was a simple reality--or elections would take weeks to finish and tabulate.

Dividing districts has always been difficult, as the country/city divide has always made for unique politics--and a huge point of contention at the Constitutional Convention. Regardless of the system used, there will always be people unhappy and disenfranchised.

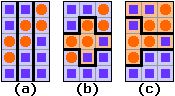

Fair, equitable, and rigged can be highlighted by the above graphic.

Fair (example 'a') could be just simply dividing the geographic area into equal chunks--and letting the resulting districts have whatever makeup is determined by the equal dividing. In this example, the orange circles are totally disenfranchised, and might as well give up on being a part of the political process.

In the case of Florida's amendment, fair, requiring the use of naturally occurring geographical boundaries, may be totally impossible to use while remaining in compliance to the rest of the amendment.

Equitable (example 'b') takes into account the natural geographic concentration of ilks. Like-minded people often live in close proximity--commonly called "community of interest groups" in legal terms. In this example, the orange circles will get 1/3 of the seats--slightly lower than their representation, yet still more equitable. This however also disenfranchises part of the blue square's regional voting power (i.e. the bottom district).

Rigged (example 'c') is drawing the districts in such a way that a political minority gains the upper hand in the political process--or, in most cases in real life, that a fairly evenly-split political district becomes rigged by the careful designing of the political map. In this case, half of the voting bloc of the blue squares, having 60 percent of the at large electorate, becomes disenfranchised by only receiving one district of representation.

The point of all of this is that regardless of the care involved, no one will ever be pleased with the result--which is why the courts have given, at times, very precise instruction on what can and cannot be done.

Court Cases Nationwide

Both parties commit gerrymandering--sometimes it's deliberate and overt, sometimes it's subtle. And while both parties commit the offense, voters have no use for these antics--broadly supporting many different referendums nationwide to end the practice with independent or bipartisan commissions dedicated to drawing electoral districts. Twenty-one states currently have some form of commission dedicated to eliminating gerrymandering.

But then, the parties show their true colors by challenge the outcomes of the referendums, trying to keep the power in "their" domain.

In 1963 and 1964, three Supreme Court rulings, Gray v. Sanders, Wesberry v. Sanders and Reynolds v. Sims, inadvertently set into motion the guise of modern gerrymandering.

Gray v. Sanders established the principle of “one person, one vote.” This seemingly innocuous principle set into motion an almost constant review of voting districts, under supposed auspices of ensuring the court’s ruling. In practice, it became an excuse for the majority party to fiddle constantly with voting districts in an effort to create favorable election outcomes.

Wesberry v Sanders strengthened Gray, but also added in requirements such as equipopulous voting districts.

In Reynolds v. Sims, the Supreme Court asserted that the goal of electoral redistricting is to ensure “fair and effective representation for all citizens.” Unfortunately, during the next 40 years, “fair and effective” became the code word for “maximizing partisan advantage.”

The court’s acknowledgement of the imprecision of the process became the focal point of manipulating the system to the major parties’ advantage:

"The federal constitutional requirement that both houses of a state legislature must be apportioned on a population basis means that, as nearly as practicable, districts be of equal population, though mechanical exactness is not required." (Reynolds v. Sims, emphasis added)

While this ruling was primarily targeted at state election maps, it carried over into federal districts. This is not without irony, since one look at electoral maps shows the inordinate amount of mechanical exactness that has been expended to create modern congressional districts.

These three rulings gave rise to a system of equipopulous gerrymandering — “an apportionment plan that complies with one person, one vote but carves lines with surgical precision to create districts designed to elect or defeat candidates from particular parties or constituencies.”

In Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), the court ruled that this extreme partisan gerrymandering was unconstitutional and harmful to the political process.

As a reaction, many states (21 so far) have established independent redistricting commissions that are nonpartisan or bipartisan in an effort to eliminate both the occurrence and appearance of gerrymandering.

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015) didn't do anything to stop the practice of gerrymandering--but it did protect the will of the people to form independent commissions through the referendum process.

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015)

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015) had broad implications that challenged the very legitimacy of the voter referendum or ballot initiative process. Currently, 27 states and the District of Columbia have some form of voter referendum in place.

In particular, the Arizona state legislature argued that the people did not have the right to redesign or delegate the powers of the legislature--and that the Constitution (Article I, Section 4, Clause 1) gives the power over elections to the state legislatures.The majority opinion (5-4), delivered by Justice Ginsburg, stressed the fact that the SCOTUS has recognized since 1916 the authority and validity of voters creating independent redistricting commissions. State of Ohio ex rel Davis v. Hildebrant (1916) stated that redistricting was left "to the laws and methods of the States. If they include initiative, it is included."

In short, Ginsburg stated that the Arizona state legislature was attempting to use wording-games, not case law to define who has authority over the matter of creating congressional districts.

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus, et al. v. Alabama, et al.

Most often, the SCOTUS doesn't directly intervene, but forces the lower courts to sort out the problems with additional guidance and requirements.

In the Alabama case, another 5-4 split decision sending the case back to trial court in March 2015, the court was asked to intervene in the legislature's attempt to overly concentrate districts with like-minded voters on the basis of race and political party.

This is an odd scenario, since districts that are compact, following natural geographical boundaries, and equal in size is the very essence of this week's Florida case. However, these same features were used to gain the upper hand in Alabama, by making black districts and white districts more concentrated.

In this case, the intent was to create a bulwark of political districts for one party that would be almost impenetrable by the other party for years to come. While following the "rules" laid out by previous court decisions, the SCOTUS maintained that the legislature still acted in a "legally erroneous" manner and that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 could not be used to defend concentrating districts by race.

This also has broad reaching implications nationwide. Community of interest laws require maps to recognize a "group of people in a geographical area, such as a specific region or neighborhood, who have common political, social or economic interests."

This ruling puts into question the legality of community of interest laws, currently used by 24 states for state legislative districts and 13 states for congressional districts.

By sending the case back to lower courts, this almost certainly ensures a quagmire for the 2016 election--with outcomes almost certainly being challenged in the courts.

Page v. Virginia State Board of Elections

Virginia has the dubious partisan honor of being the only state in the U.S. to have the Democrats control all at-large elected positions (President, Governor, U.S. Senators), while the Republicans maintain the upper-hand in all elections at the congressional and state legislative district level (State Senate (21-19), State House (66-33), and U.S. Representatives (8-3)).

This should be an immediate signal that something is very wrong with the way that the voting maps are drawn in Virginia.

Part of this is the country/city divide--over 75 percent of the population lives in the cities. This makes for drawing congressional districts that are compact around the cities, sprawling in the country--3 of the 11 districts take up more than 60 percent of the state's geographical area.

The country/city divide also has a partisan component--that voters in the cities are more likely to be Democrats, while voters in the country are more likely to be Republican. This reality almost completely ensures that the 6 rural congressional districts will vote Republican, leaving the other 5 "competitive."

This is not entirely unusual, as the country/city divide in the U.S. as a whole is fairly profound--with over 80 percent of the total population living in cities.

What this case does involve is the fact that the board of elections attempted to make an urban district (Va-3) more Democratic in an effort to make the 3 rural districts (Va-1, 4, & 7) surrounding it more Republican.

The plaintiffs challenged that this was racially motivated, and while the federal district court found in favor of the plaintiffs, they did not isolate the motivation to just race, but stated that the board of elections had mixed-motives that were still unlawful.

The implication of this ruling is that further court challenges could use the Voting Rights Act of 1965 without having to prove that race was overriding motivation for the gerrymandering.

The district court gave the board of elections until Sept. 1 to redraw the congressional maps, unless appealed to the SCOTUS. Considering the outcome of the Alabama case at the SCOTUS, appealing might only serve as a stalling tactic to the inevitable redrawing of the maps.

Parrott et al v. Lamone, et al 01849

Filed June 25 in federal district court in Maryland, Parrott et al v. Lamone et al 01849 is a testament that gerrymandering is really done by both sides of the political spectrum.

In Oct 2011, Democratic presidential-hopeful, then-Gov. Martin O'Malley signed into law a new redistricting plan that changed voting districts for 27 percent of the state's population, making Maryland one of the most gerrymandered states in the union.

The drawing of the districts is done with such surgical preciseness that the third district zigzags through the heart of the state, carving out a narrow band of territory.

According to the court documents filed by the plaintiffs, this is at least the fifth lawsuit against the redistricting plan--with the first four failing in the courts for a variety of reasons, including: the courts felt like they had no viable alternative, the plaintiffs claims were nonjusticiable and supported by conclusory allegations, the claims were voluntarily withdrawn, and that the claims lacked a judicially manageable standard that could be used to resolve the case.

Even without the lawsuit, the congressional maps are likely to come under the review of the new Republican governor, who has already promised to set up an independent, bipartisan committee to "fully reform this process."

The relevance of this case, however, is a demonstration of how difficult it is to bring a claim of gerrymandering before the courts. The claims have to have both justifiable accusations and a plan for remediation, otherwise the courts will stay silent.

Florida and Beyond

Florida, and the rest of the nation as a whole, is going to continue to have problems creating congressional districts that maintain the spirit and intent of the law.

Florida is highly urbanized, with more than 90 percent of the population living in cities and is exceedingly diverse racially.

When looking at all of these cases together, though, Florida is going to have some difficulties in following all of the guidance the courts have given.The voter approved ballot measure is safe due to the Arizona ruling, but the ballot measure requiring the use of existing city, county and geographical boundaries may come under scrutiny as community of interest laws come under fire.

And while trying to ensure equal populations in Florida's 27 congressional districts, it will be difficult to avoid the current end result of several mythical creature districts looking like snakes, seahorses, and even a rhinoceros.

The United States, over the next 15 years, will become more urbanized, exacerbating the difficulties in drawing congressional maps that are equipopulous, while compact and contiguous.

The courts will still be packed with cases, as newer and "better" forms of gerrymandering appear to capitalize on the demographic changes.

But in the end, gerrymandering will never be fully removed from American politics until the electorate abandons the partisan two-party system that refuses to listen to their ballot initiatives demanding equity in the drawing of congressional districts.