How Ted Cruz Won His Senate Seat With Just 632,000 Votes in a State of 27 Million

Ted Cruz (R-Texas) announced the launch of his 2016 presidential campaign, making him the first high-profile, major party candidate to do so. Cruz is known as a polarizing figure on Capitol Hill; his hardline stances on issues like immigration, climate change, and health care reform have made him the subject of countless headlines since he assumed office in 2013.

Even in Texas, he is a hardliner. So how does someone so polarizing get elected?

Ted Cruz was chosen to be the next junior senator in Texas by about 4 percent of the eligible voting population by virtue of winning his low-turnout (under 9%) Republican primary runoff. This is a fact about almost all primary elections today that is often missed by media talking heads and politicos.

Cruz didn’t place first in the 2012 Republican primary; he placed second behind then-Lt. Governor David Dewhurst. However, Dewhurst, who received roughly 45 percent of the primary vote, was not able to garner enough votes to avoid a runoff. Cruz placed second with approximately 34 percent of the vote.

The 2012 summer runoff election produced an even worse turnout -- 8.5 percent -- the lower the turnout, the more ideologically extreme the voters tend to be.

And in that runoff, Cruz garnered 57 percent of the vote, while Dewhurst received a little over 43 percent. Cruz then advanced to the general election, where voters got to choose between him and Democrat Paul Sadler. In a Republican-dominated state, this ‘election’ wasn’t a real competition.

In short, Ted Cruz got 631,812 votes in the primary to effectively win a seat that represents 26.97 million people.This is the reality of our current partisan elections. Republican voters, who still make up a solid majority of the Texas electorate, were not going to vote for a Democrat. Sadler, for example, was called the “sacrificial lamb” in the election because the minority party was not even considered consequential — and neither were any voters who didn’t participate in the Republican primary election(s).

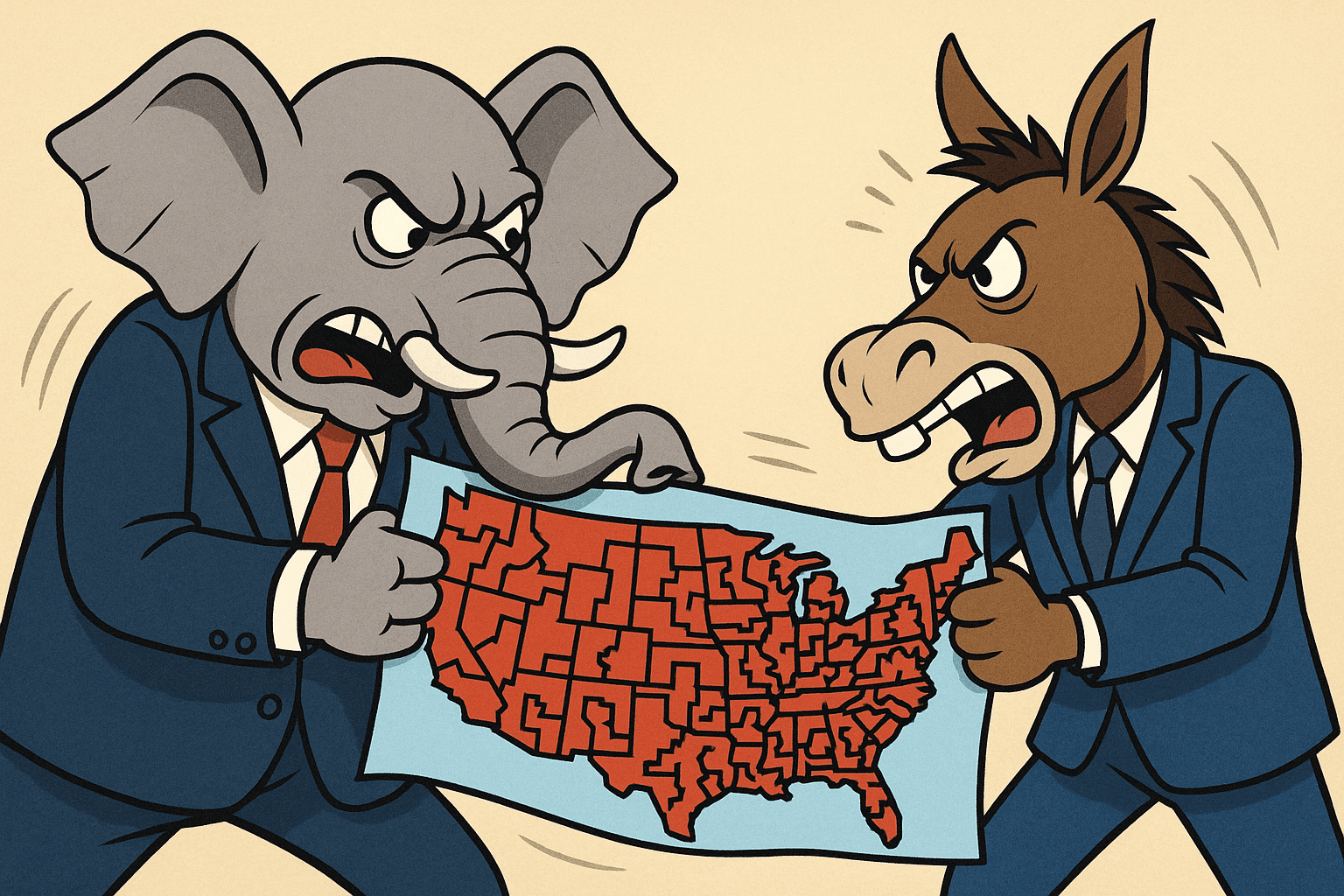

The current system treats any votes outside the majority party as meaningless. Democrats have little power to sway statewide elections in Texas, much like Republicans don’t have influence in districts controlled by Democrats.

Under a nonpartisan system, however, like the new systems in Washington state and California, the results would likely have been much different. In these states, all candidates and voters, regardless of party affiliation (or lack thereof), participate on a single primary ballot. The top two vote-getters (again, regardless of party affiliation) advance to the general election.

In an op-ed published on The Hill, Markos Moulitsas, the founder of the Daily Kos, claims that top-two is a failure after two election cycles in California.

Moulitsas claims the system produces an unrepresentative government by citing one example in 2012 where too many Democrats ran in the 31st congressional district, a district where the constituency tends to lean Democratic. This resulted in two Republicans advancing to the general election because of how the votes were split.

“How is a right-wing Republican representing a manifestly liberal district a service to democracy? It’s not. In fact, it makes a farce out of our representative system,” he writes.

However, what Moulitsas fails to mention is the Republican, Gary Miller, no longer represents that district. Democratic U.S. Representative Pete Aguilar was elected in the 2014 election.

He also fails to mention that 90 percent of elections across the country today are actually ‘decided’ in low-turnout primary elections due in large part to partisan gerrymandering.

So, under the traditional partisan primary systems, we have representatives all over the country being ‘elected’ at the primary stage of the election when just 10 percent of voters nationwide are participating.

How does that serve democracy?

Under California and Washington’s nonpartisan systems, candidates cannot solely appeal to voters affiliated with their party because the party's voters are no longer the sole factor in deciding the election. Most of the time, voters outside the majority party end up deciding who wins the race, which means majority party candidates have to listen to all voters or risk losing the election.

Cruz’s hardline, ideological positions on issues and his unwillingness to work across the aisle would have appealed to some voters, but would be a difficult sell in a nonpartisan election.

Then again, most representatives today don’t ever have to consider voters outside their party.