What America Should and Shouldn't Do to Implement Proportional Representation

NATIONAL -- There is no doubt that there are some IVN readers who support some form of proportional representation, often seen as a voting scheme that maximizes representation and makes every vote count.

But the real question is, what would be the avenue to implement proportional representation nationwide? What are the roadblocks and potential legal challenges?

To answer these questions, we have to examine the history of how we got to our current two-party voting system.

History of Current Voting Laws

Between 1890 and 1910, candidates outside of the Democratic and Republican parties captured over one-fourth of the total vote for state governorships, U.S. House, Senate, and the presidency in Alabama, California, Georgia, Idaho, Montana, Minnesota, Nevada, Texas, and Washington.

Between 1930-1960, no candidate outside of the two-party system ever collected more than 25 percent of the vote in any state for those races.

Three reasons are usually presented for this: the passage of anti-fusion laws, direct primaries, and the New Deal platform of the Democratic Party.

A brief overview of the American voting system, along with many of the historical reasons for switching to the modern system can be found here.

Prior to anti-fusion laws, it was common for candidates to run under multiple party platforms, and the "third-party" system thrived.

A candidate might run under both the Democratic and Progressive parties, for instance, with votes for each counting toward their tally.

This also eliminates the "spoiler" feature of independent or third-party candidates -- voters could pick major-party candidates who promised to adhere to the ideology of the third party, thereby giving the voter a clear-cut ideological basis for voting for a major-party candidate.

This form of voting severely undermined the power of the two-party system, as the parties had less control over the ideologies of its candidates. Beginning in the 1880s, this voting format became the target of state laws prohibiting fusion voting

Forty-two states plus the District of Columbia prohibit fusion voting. The Supreme Court upheld Minnesota's anti-fusion law in 1997, setting the legal precedent to justify the existence of these laws.

A very interesting case study on potential state-level constitutional issues for challenging anti-fusion laws in New Jersey can be found here.

The obvious outcome of primaries is the creation of general elections that are comprised of one candidate from each political party.

While this seems normal today, during much of our history this was not the case; especially, when coupled with fusion voting -- a party might be represented by multiple candidates.

This, of course, was seen by the party leaders as a dilution of their base, splitting their ideological vote among multiple candidates.

Direct, closed primaries also create a system where taxpayers are funding the candidate selection proceedings of supposedly "private" organizations.

By claiming to be private organizations, these groups can pick and choose their rules, as well as who can vote in the primary process. This creates a system of cronyism and abuse, the worst blend of public politics and private pandering.

In states with partisan primary systems, all voters have to pay for primary elections, regardless of whether or not they are actually allowed to participate.

A coalition of individual voters and nonpartisan organizations are challenging the constitutionality of the closed primary system in New Jersey. The U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals has calendared oral argument for March 17, 2015, but has not actually decided to grant the oral argument.

Meanwhile, major parties nationwide are trying to close their primaries or keep their primaries closed, arguing that nonmembers are influencing or would influence their elections.

From the 1900s through the 1960s, countless governments worldwide were felled by communist, socialist, or fascist revolutions.The depression felt by much of the world struck the Western industrial powers when the stock markets collapsed in 1929.

America faced a choice: take the chance of a widespread revolution or implement sweeping social changes.

Widely known is that President Franklin D. Roosevelt campaigned on a platform of cutting Americans a "New Deal," but lesser known was his promise to include ideas from the various progressive parties into the New Deal.

It was the New Deal that created the modern political terms "liberal" and "conservative." Conservative Republicans were against the program, while liberal Republicans joined with Democrats to support it.

The New Deal created a significant power shift in America. The presidency was claimed by Democrats in 7 out of 9 elections from 1932-1968, and the party mostly controlled Congress for half a century.

This powerful collaboration to produce the New Deal is seen by some to be one of the most significant reasons for the decline of the third-party system, as the majority of those parties were seeking significant social change in America and chose to join forces with the Democratic Party to create the New Deal.

While this view is certainly debatable, the inclusive nature of the Democratic Party gives it plausibility, as well as many third-party candidates taking shelter from the anti-communist witch hunts in an established political party.The key takeaway from this is that our modern two-party system is not the voting system that has always existed in American politics, but instead is only a little over 100 years old. Even sacrosanct principles like the secret ballot are relatively new principles; we can and do change voting systems and laws in this country.

Perhaps we are ripe for a change in today's system of entrenched partisanship, where independents now make up almost half of the total vote.

The Modern Two-Party System

For whatever reason, we are now left with a two-party system that actively attacks nonpartisan or third-party attempts to run for office.

The two major parties are well-funded, getting funds from the federal government, subsidies (in the form of paid primaries) from state governments, and almost limitless private contributions.

Even with this considerable public financing, the parties hide behind the pretext of being private organizations, in an effort to keep alive the system of closed primaries.In general, the two-party system is not ideologically compatible (at least in terms of the parties' behavior) with proportional representation. The two parties seem content to slug it out in battleground states, occasionally addressing a significant challenge in "safe states."

Economics probably plays a large role in this -- any system that makes every state a battleground state would make campaigning less centralized, would rely more on local ideologies and political support, and would cost the parties significantly more in campaign dollars.

In such a system, the two parties would not be able to only focus on a handful of battleground states; they would have to focus on all contests, or take the chance of significant losses.This would represent a significant decentralization of American politics: from the hands of national party leaders to local organizers and grassroots movements.

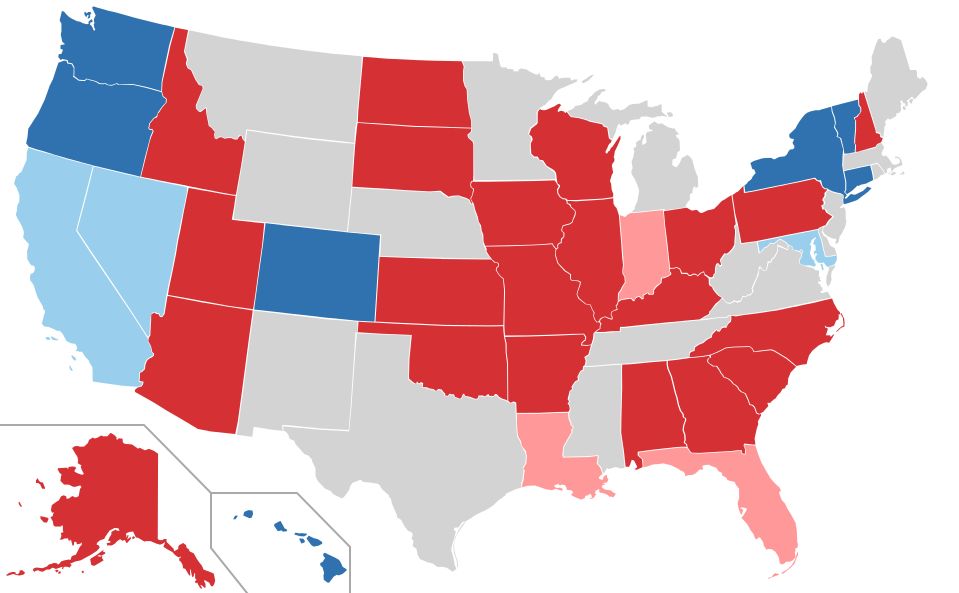

In 2014, the Democrats faced one of the worst election maps the party has ever experienced in modern politics, and the Republicans were able to exploit the vulnerability and make considerable gains in both the House and Senate.Likewise, in 2016, the Republicans face an equally challenging election map with over twice as many Senate seats up for grabs as Democrats -- and in a presidential election year.

Does it really seem democratic for a party to live and die by the election map, instead of making every state count?

While proportional representation would probably benefit the voters, the party bosses will most certainly fight any proposed changes on a national level.

A Constitutional Amendment Is NOT The Answer

Any scheme that requires a federal constitutional amendment is likely to be doomed before it even starts.

There hasn't been a start-to-finish amendment to the Constitution in over 44 years (the 27th Amendment was intended to be a part of the Bill of Rights in 1789).

The Constitution has been amended 27 times in America's history since 1789.Only three of the amendments took longer for ratification than the Bill of Rights (two years, two months), with the shortest being the 26th Amendment (3 months, 8 days) and the longest being the 27th (202 years, 7 months).

The 26th Amendment, setting the nationwide voting age at 18, came out of a Congress as bitterly divided and entrenched as today's Congress. During the 92nd Congress, the House and Senate were held by a less than super-majority Democratic Party; yet the 26th Amendment passed both chambers overwhelmingly (94-0 in the Senate, 401-19 in the House).

The point is, constitutional amendments can and do pass even the most bitterly-divided Congresses, but there has to be exceptionally broad appeal to the content of the amendment.

Amendments with even the slightest hint of party platform or partisanship (or that threaten the current system) are unlikely to pass. This has been the historical norm, with the possible exceptions being Civil War-aftermath amendments and the 18th Amendment.

A voting scheme amendment would have practically zero chance of ever clearing congressional approval.

Even if an amendment was ratified, it doesn't mean the Supreme Court would follow its intent.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified specifically protecting the right of former slaves and other races to vote:

"Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation." -- Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

This was the third amendment to the Constitution that granted Congress enforcement power, traditionally held by the executive branch or the states.

Almost 100 years later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, in which Congress enforced the 15th Amendment in states that were reluctant to make good on its promises. At the heart of the legislation, these states could not change their voting laws without the advance consent of the federal government.

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key portion of this law -- namely, the formula to determine which states would have to seek federal approval to change their election laws -- in a 5-4 vote. In particular, as Chief Justice Roberts said in the majority opinion, the majority believed that the Congress was not properly enforcing the Constitution by using an outdated law.

Justice Ginsburg wrote a scathing dissent, accusing the majority of not following the letter or intent of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The lesson to be learned in all of this is that amendments are hard to ratify; they must be predominately nonpartisan, and even if passed, there is no guarantee that the courts will follow its letter or intent.

While state constitutional amendments, especially those by ballot initiative, are fairly easy to accomplish, they are almost always challenged in the federal courts.

This is the biggest danger to any sweeping movement of voter reform -- the fact that creating a constitutional amendment is unlikely, which in turn makes federal court battles a significant likelihood.

The climate in the Supreme Court when it comes to voting rights is convoluted at best, and outright hostile to the individual at worst.

Rulings like the 2013 split-decision to overturn portions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Citizens United decision of 2010, or even the contradictory voting rights decisions in 2014 on states changing voting deadlines and early voting rules, have created an ideological war within the Supreme Court on voting rights.

Local and State Grassroots Efforts ARE the Answer

If one truly believes that every vote should count -- in every state and every contest -- then the best place to start for voting reform is at the local level. This is not without danger because courts can and do rule measures as unconstitutional.

The benefit, however, is the ability to create a broad base of public appeal through grassroots efforts.

Currently, 27 states plus the District of Columbia have some form of voter referendum or ballot initiative available, with even more local governments and municipalities embracing this form of direct democracy.

These states should be the first battleground for implementing proportional representation, using the existing system of voter referendum or ballot initiative.

While the state-level would yield the biggest prize, supporters of proportional representation would be foolish to ignore the local and municipality levels of government. California's top-two and the Amarillo Independent School District's cumulative voting system make excellent case studies for how proportional representation can be implemented:

California's nonpartisan, top-two system has had a rocky road to implementation, with 2012 being the first election under the new system.The top-two system is not a true form of proportional representation. Under this system, all voters and candidates, regardless of party affiliation, participate on a single primary ballot. The top-two vote recipients in the primary then move on to the general election -- again, regardless of party affiliation. This sets up the possibility of a general election between candidates of the same political party.

Even though it is not a true form of proportional representation, "Top-Two" is still widely seen by advocates as giving the voter a greater chance to be heard.

Prior to Top-Two and the semi-closed primary system that came before it, California had what is known as a blanket primary system. In this format, voters could cast a mixed-ticket ballot, meaning they could pick candidates from any party for individual offices, but the top vote-getter from each party would still advance to the general election. This system replaced California's closed primary system, and was approved by a voter referendum in 1996 with a super-majority of votes.

In 2000, the Supreme Court struck down this version of the blanket primary system (used in 3 states) in California Democratic Party v. Jones. True to the past 100 years of our voting history, the major parties do not like anything that limits their power.

Justice Stevens wrote in the dissent:

"This Court's willingness to invalidate the primary schemes of 3 States and cast serious constitutional doubt on the schemes of 29 others at the parties' behest is an extraordinary intrusion into the complex and changing election laws of the States."

Once again, the parties showed their true colors: the belief that they, not the voters, "own" the primary system.

In 2004, Proposition 62, a nearly-identical scheme to the current top-two system, failed to pass by a 46.1 to 53.9 percent margin.

In 2010, Proposition 14, the current Top-Two law, passed with 53.7 percent of the vote.

Proposition 14 was immediately challenged by political parties in the courts, but the law has so far survived each challenge. A history of the legal challenges can be found here.

What can be learned from this is that even with considerable challenges, the will of the people can be heard and voting systems can be changed.

While California voters relied on the ballot initiative process to implement Top-Two, the Amarillo Independent School District's (AISD) battle over proportional representation was fought in the courts.In response to under-representation of minorities in school district boards, 57 school districts in Texas switched to some form of proportional representation between 1991 and 2000 to resolve lawsuits involving the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Then Governor George W. Bush supported this effort and signed into law measures that made it easier for school districts to enact such policies.

The AISD had serious representation problems. Prior to the 2000 election, only one minority candidate had ever been elected to the school board, even though making up 22 percent of the electorate.

Shortly after the 1998 election, a lawsuit was brought against the AISD claiming systemic disenfranchisement of minority voters because of the single-district, winner-take-all system of voting.

Both sides agreed to implement cumulative voting as a realistic voting scheme to resolve the lawsuit. The AISD is the largest government-body in the United States to use a cumulative voting system.

After the first two election cycles with cumulative voting (2000 and 2002), the school board featured two Latino members, and one African-American. Forty-three percent of the seats were held by minority representatives -- considerably larger than the demographics of the population at large.

The single greatest advantage to cumulative voting is that voters can specifically emphasize their preferences by giving candidates more than one vote.

There are several disadvantages to this system:

- It is not a true proportional voting system as demonstrated by the over-representation of minority school board members in the 2000 and 2002 elections in Amarillo.

- It requires huge amounts of political party involvement to ensure that the voting blocs stay in lock-step.

- Political parties have to “self-regulate” the number of candidates vying for the election — too many candidates from any one party has the potential to dilute the vote (i.e. the party receives the most ballots, but no individual candidate receives enough votes to win a seat).

- It would be unlikely for minor-party or independent campaigns to be able to organize sufficiently to capture a significant portion of the vote.

- It perpetuates the false paradigm that all independent or minority campaigns are representative of an entire bloc of voters. For example, Ben Carson and Barack Obama are both African-American males. However, regardless of the demographic groups they share, they are polar extremes politically. Neither one could possibly represent the entire African-American voting bloc. This creates a false sense of diversity and proportionality.

Nevertheless, the system did do what it was designed to do: it gave racial minorities a voice in the political process.

Professor David Rausch of West Texas A&M has conducted significant research on the AISD cumulative voting scheme. He found, contrary to critics, that the system was well understood by voters, and had lower error rates in balloting than in traditional voting methods. His study can be found here.

Proponents of proportional representation should be taking the fight to every level of government, using legislative measures, ballot initiatives, and even the court system to advance the cause of giving voters greater representation.

Proponents don't need the big win of a nationalized voting scheme right off the bat; simply implementing the system municipality by municipality, state by state will sufficiently and effectively advance the cause.

Dr. Kathleen Barber, a retired political science professor, has two excellent works on proportional voting.The first, Proportional Representation and Election Reform in Ohio, is a case study on the implementation, application, and subsequent fall of proportional voting in Ohio from 1915-1960.

In her analysis, she admits that proportional voting in Ohio may have fallen victim to being ahead of its time -- falling prey to political party leadership, racism, and Cold War fears.

One of the "dangers" of proportional voting is the chance (and even likelihood) of unpopular ideas being represented in government. For instance, during Ohio's experiment, several members of communist groups were elected to various positions within the government -- definitely a faux pas of Cold War politics.

Her second work, A Right to Representation: Proportional Election Systems for the Twenty-first Century, provides a history and explanation of various systems, as well as ideas for implementing proportional voting in the 21st century.

While geared toward Canadian politics, Proportional Representation: Redeeming the Democratic Deficit, an academic journal article by Liz Couture, describes the necessary local, grassroots education that needs to be implemented to change politics nationwide successfully.

Strategic Voting and Coordination Problems in Proportional Systems: An Experimental Study, a collaborative academic journal article, examines the principle of parties having to defend seats by offering less-than-full slates (and other strategies) in proportional systems.

This same pitfall was discussed in a past IVN article on the mechanics of three different proportional systems. In a more recent IVN article, Andrew Gripp offers a critique of the mechanics of California's top-two system.

This is by no means a definitive list. There are hundreds of academic journal articles, as well as books and periodicals on the subject of proportional representation systems, highlighting the growing interest in the different types of systems and their benefits.

Photo Credit: Carolyn Franks / shutterstock.com