While Crime Rates Drop, Number of Life Sentences on the Rise

trekandshoot / Shutterstock.com

The nation's response to criminal deviance over the past 30 years, from harsh sentencing to arbitrary bail and overwhelmed facilities, is while entirely justified, a good example of growing ideological polarization. Unfortunately, the economic crisis of the late 1970s fell hardest onto these very groups, with deep cuts to safety net subsidies.

Bruce Western, criminal justice professor at Harvard, says the subsequent crime spike was no accident, but wasn't predictable by the era's standards.

With public support, the corrections industry grew, expecting crime to drop. When longitudinal data officially disagreed, operations intensified into enforcement expansion. Statistically, retributive corrections exacerbates criminality, but the "war on crime" became prominent in both the public and political level.

Now the nation's stuffed prison population has declined for three consecutive years with a 2.1 percent decrease in state prisoners in 2012 alone (federal prisoners increased by 0.7 percent). This gradual decline is attributable largely to California's two-year-old realignment efforts.

Over half of last year's incarcerated population reduction occurred within California corrections, setting up the state as a modern crime-fighting frontier. However, California retains daunting statistics like most life convictions (30 percent of state inmates, 25 percent of national lifers). The impact of a 1972-76 ban on capital punishment.

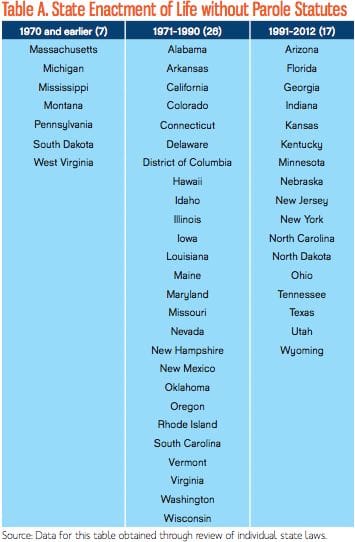

Even as the US finally begins slimming incarceration, a 30-year upward growth in new lifers isn't slowing with incarceration. Life sentences expanded in the 70s after a brief ban on capital punishment sent no-tolerance crime-fighters to the legislatures of dozens of states.

Between 2008 and 2012, during the first total incarceration decline in three decades, new lifers rose 11 percent, and lifers without parole spiked 22.2 percent.

According to a recent report from the Sentencing Project, lifers have quadrupled since 1984, including 10k sentenced as juveniles, of which one in four will never see a parole board:

One in nine prisoners is now serving a life sentence and nearly a third ...are certain to die in prison.

For those parole-eligible, a 1991 admission could expect to serve an estimated 21.2 years before a realistic chance at release. If admitted in 1997, however, an inmate could expect to serve 29 years before satisfying a board, a 37 percent increase over only six years. The figure has likely grown since then.

Even as states and counties struggle to cut short-term detainees, more costly lifers are arriving.

About a quarter of life convictions hinged on common nonviolent offenses, under one of two no-tolerance "strikes" laws, and at least 75 percent of lifers are black or Latino. In comparison, blacks are 23 percent of the general inmate population.

Fewer are making or even qualifying for parole, despite staff testimonies that -- facing indefinite confinement and astutely avoiding melodrama -- they are eventually the most responsibly structured inmates, rarely reoffending post-release.

Legislation, it seems, occasionally draws more from the gut than the data. Just as the relative harshness of maximum sentencing has little correlation to local crime rates, neither do California bail amounts.

San Bernardino's bail is five times San Diego's bail for an identical crime. Not only has county realignment obstructed regional reform through dangerously autonomous strategies, but undoing and preventing these inequities depends on the likely, yet inconveniently intangible explanation: fear of crime and perception of danger.

If legislating from the gut had such drastic consequences for the state's ability to move beyond warring with crime to actually stopping it, we can only hope that the monopoly of politics over policy on the national stage can be mitigated before it's too late for sustainable recovery.