U.S. Presence in Afghanistan Led to Increase in Country's Opium Supply

Afghanistan's third straight year of opium production increase has stirred concerns that after foreign departure, it may become “the world’s first true narco-state.” However, the United Nation’s report on this growing issue is glaringly incomplete.

The United Nation’s Office of Drug and Crimes (UNODC) 2013 World Drug Report credited Afghanistan with 74 percent of global opium production -- a conservative estimate -- which placed Afghanistan as the world's top opium producer yet again.

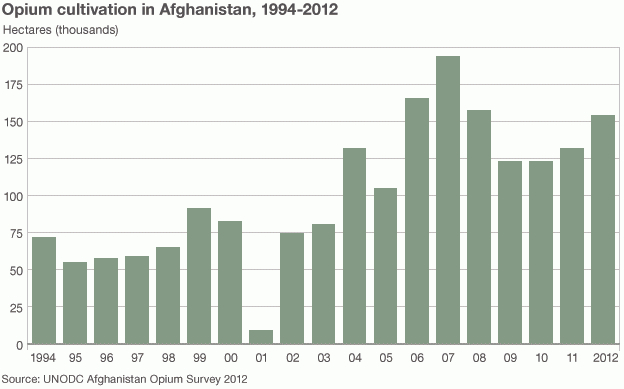

Production of opium has increased since the arrival of foreign boots on the ground. This marks a contradiction to the widely trumpeted concerns that foreign departure will lead to an increase in opium production.

While the region has always been known for production of opiates, a less cited statistic is that its production since the 2001 U.S. invasion has reached heights it had previously not achieved.

The United Nations claims the need to shut down production of the drug as a means to cut funding to the Taliban. However, a relevant note from recent history shows the Taliban was the largest prohibiting factor of opium production in the year prior to American intervention.

In 2000, Afghanistan produced 3,300 tons of opium, but a harsh Taliban prohibition on the drug cut it to 185 tons. The 2001 yield was the lowest level of Afghanistan opium production in years. The low yield made a large dent in the global opium supply -- a multi-billion dollar industry.

The United States invasion, and resulting destabilization of the region, saw opium jump back up to pre-ban levels and continue to soar past them.

The departure of foreign intervention from Afghanistan is not likely to be accompanied by a drop back to 2001 yields. It does, however, highlight the contradictions between the idea that America stands as the last shining hope of the Afghan War on Drugs and the reality of a genuinely messy situation.Another reason for skepticism surrounds the Taliban's funding. Poppy production supplied the Taliban with only $100 million in 2012, a number the UN reportedly called an indication they are not taking advantage of the $4 billion industry in the region. The Taliban garners a larger percentage of its funding from protection contracts coming through contractors from the United States and other foreign nations.

This is not the only incomplete facet of the UNODC report. While the report has comprehensive breakdowns for opium, usually heroin, traffic in Europe as well as Canada, its findings concerning heroin in the United States are incomplete.

The report claims that Canada is the only country in the Americas who receives its heroin primarily from Afghanistan. Citing the rest of the countries as receiving supply from within the Americas. It goes on to claim that the United States supply comes from Mexico and Columbia, Columbia being the main supplier.

The UNODC admits this information “is inconsistent and does not fully explain the heroin supply situation in the region.” The inconsistency the report pursues is that cultivation should be greater in Mexico than Columbia despite the United States claims.Then it states, “there is insufficient information about the role played by heroin originating in Afghanistan for the United States market.”

There are good reasons for the UNODC to fill in this gap of knowledge with a more comprehensive investigation.

It doesn’t seem too far fetched that some of the unaccounted for supply of United States heroin could from Afghanistan, considering it is the largest supplier for the US' northern neighbor, Canada, and responsible for at least 74 percent of the global supply.

This has historical precedent from the United States' Cold War involvement in the region. A study by Alfred McCoy cited that Afghanistan supplied 60 percent of U.S. demand in 1979.

The UN report on this issue leaves much to be desired. The numbers it does provide shed light onto what has become a major issue concerning U.S. departure from Afghanistan.

The weaknesses mentioned above provide a watering hole for conspiracy. However, the story they tell seems, above all, to highlight yet another confusing quagmire among the many that have defined a legacy of unsuccessful foreign policy in the Middle East.