Indicting Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, America’s Favorite Villain

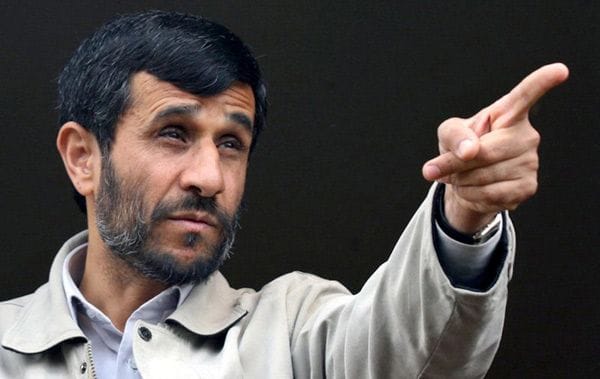

Credit: Brecorder.com

During the last presidential debate on Monday, Mitt Romney pledged to indict Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. How he would do this leads into a convoluted mess of international law that we will attempt to unwind.

Romney was referring to an indictment under the Genocide Convention, an international law that was approved and entered into force in January 1951 by the General Assembly of the United Nations.

The law confirms that genocide, whether in times of peace or times of war, is a criminal act under international law. Under the terms of Article II of the Convention, the following acts are considered genocide if they are committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Under Article III of the same convention the following acts shall be punishable:

- Genocide;

- Conspiracy to commit genocide;

- Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

- Attempt to commit genocide;

- Complicity in genocide.

There have been two breaches of the convention pursued by the international community. The first time the law was enforced was in response to the Rwandan genocide, when the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda found the former mayor of a small town in Rwanda guilty of nine counts of genocide. Several days later Jean Kambanda became the first international head of state convicted under the law.

In 2007, Serbia became the first country to be convicted under the Genocide Convention -- not for their direct role in the Srebrenica genocide, but for their failure to transfer persons accused of genocide to the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia.

That same year, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad may have stated that he wants to see Iran wipe Israel off the map. Stating his intentions to wipe Israel off the map could only be considered a direct and public incitement to commit genocide. The court would ultimately decide whether or not this statement to a group of Iranian students is actually inciting genocide.

The difficulty lies in prosecuting the head of state. The international community has recognized that temporary military tribunals established in each state post-conflict is not ideal and, as such, the ICC was established at the Hague. This does remove the difficulty of establishing venue for the case, except that neither the United States nor Iran is a party to the ICC. If countries are not parties to the ICC, then a question of jurisdiction arises, and Ahmadinejad would not be indictable in that court.

An alternative arises under the Genocide Convention as each country that is a party to the international law also adopts the law into their domestic legal system. This means that Ahmadinejad could be indicted in a federal court in the United States. However, he would have to commit the offense within the boundaries of the United States or be a national of the United States.

Unless Mitt Romney intends to make a radical policy shift and join the ICC, along with Iran, it’s impossible for Ahmadinejad to be indicted in the Court at the Hague. Ahmadinejad’s prosecution would also be limited in the United States to acts committed here, which have not occurred.

If a voter bases their decision to support Mitt Romney based on his insistence on indicting Mahmoud Ahmadinejad alone, he or she will be disappointed. Although the tough talk is present in the political discourse and many Americans may agree that the Iranian president should be indicted under international criminal law, it is simply unlikely that the Iranian president will face the rule of law under the Genocide Convention.