Eric Holder and the Abuse of Executive Privilege

In the past few weeks, the "Operation Fast and Furious" scandal has not only stirred up partisan bickering, but also turned the spotlight on a controversial presidential power: executive privilege. The doctrine of executive privilege has a background in the Watergate scandal.

When President Nixon realized the tide had turned against him, and the evidence of wrongdoing was about to be released, he tried to invoke "executive privilege," claiming his office gave him broad authority to keep secrets, even from prosecution by other branches of the government. In US vs. Nixon, the Supreme Court ruled that there was no broad and unlimited executive privilege, although secrets could be kept in some cases.

In this landmark case, the Court determined that executive privilege was primarily for matters involving national security, and that in most other cases, investigators could look at the evidence. The ruling stated:

"The President's need for complete candor and objectivity from advisers calls for great deference from the courts. However, when the privilege depends solely on the broad, undifferentiated claim of public interest in the confidentiality of such conversations, a confrontation with other values arises. Absent a claim of need to protect military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets, we find it difficult to accept the argument that even the very important interest in confidentiality of Presidential communications is significantly diminished by production of such material for in camera inspection with all the protection that a district court will be obliged to provide."

This very meaty quotation basically says this: While it is important that the President should be able to speak confidentially with advisers, he can't simply cite public interest and keep documents or testimony secret to avoid investigation unless national security is at stake.

In today's controversy, the issue is complicated by guns and votes. "Operation Fast and Furious" was a misguided attempt to bring down criminals by giving them illegally purchased guns. Those guns were later found to have been used in crimes, including the shooting death of a Border Patrol agent.

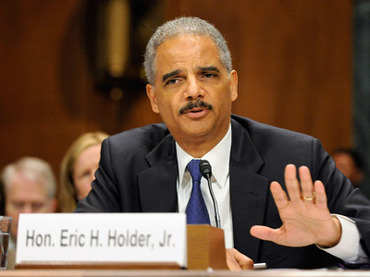

Now in an election year, Republicans are eager to implicate the Obama administration and tarnish his image. Democrats are just as eager to quiet the investigation and keep Obama above the fray. Recently, the Obama Administration invoked executive privilege to defuse the scandal. In a letter, Attorney General Eric Holder says he is:

"...very concerned that the compelled production to Congress of internal Executive Branch documents generated in the course of the deliberative process concerning its response to congressional oversight and related media inquiries would have significant, damaging consequences."

This is undoubtedly true. Who will be damaged, though? The American people, or the men and women behind the scandal and its aftermath? This is where the Supreme Court's ruling becomes relevant. Yes, the President has the power to keep executive secrets, but only if crucial national interests are at stake. Our "national interests" are notoriously broad.

I have yet to hear of how releasing these documents would undermine national security. Unlike strategic military plans, which might be deadly if they fall into the wrong hands, these documents are no longer relevant to criminals or terrorists, but they are relevant in the pursuit of justice and truth. Eric Holder goes on to justify secrecy by claiming that release of the materials:

“...would inhibit candor of such Executive Branch deliberations in the future and significantly impair the Executive Branch’s ability to respond independently and effectively to congressional oversight."

Taking off the PR spin, this means executive branch employees and advisers don't want to have to worry that what they are saying and writing will come before a congressional investigation. In a sense, this is a legitimate concern. We don't want strategy discussions to be in the newspapers. However, there are no such concerns in this case.

This is an abuse of executive privilege, a political attempt by the President to hide what really went on in his administration. The administration cites "damage" and "consequences" if the documents are released. Maybe that damage would be to the federal bureaucrats in charge of Operation Fast and Furious.

Independent voters by now realize that the point of this investigation is no longer justice, but a partisan squabble with a heavy dose of election-year posturing. There are three views of the investigation. The first is best expressed by Rep. Steve King (R):

"That means that implies very strongly... that this information that Darrell Issa is searching for and trying to subpoena links inside the White House itself, most likely that the information was prepared for the president’s eyes and perhaps it was seen by the president.”

This view is marked by an almost eager interest in nailing the administration (and hopefully President Obama) to the wall, and then exploiting that in the election. The Republicans have found a new toy, and they want to see what it can do. They are not focused on justice, but on mudslinging and votes. Executive privilege is only legitimate when they are the ones using it.

The second view was stated by Obama's communications director Dan Pfeiffer. This whole scandal is just a "politically motivated, taxpayer-funded, election-year fishing expedition." This view is not focused on justice either. Democrats are trying to sweep everything under the rug. It doesn't matter. Let's focus on jobs, not on little issues like dead Border Patrol agents or guns in the hands of criminals or lies or cover-ups. Executive privilege is the magic eraser in the hands of the powerful.

The third view is that the investigation is necessary to preserve what little justice and transparency still exist in our government. Executive privilege is being used to cover up destructive policies, and history shows us that this is the first response of a desperate administration. The investigation needs to proceed, and whoever is involved should be dealt with as law and common sense dictate, while investigators try to ignore the coming election and the concerns it brings. Is a fair and non-partisan investigation too much to ask? In today's Washington, maybe it is.