The American System

He came up with what he called the American System. His name was Henry Clay of Kentucky. In 1806, Henry Clay was elected to the US Senate by the Kentucky legislature. At which, he set out at once for the nation's capital city, Washington DC. Part of his route would be via boat while more of it would be via the nation's roads... or what were considered roads at that time. It was upon this journey that Clay's zeal for an internal improvement program for the nation were formed. He had already had the concept for such a program while serving at the state level, but now he wanted it moved to the national level, and it would become a lifelong goal while he served in Washington. Clay's American System had three parts to it... a tariff (which was passed in 1816), a national bank (which Clay originally favored not rechartering the First Bank of the United States created during the Washington administration, but then realized the error of that and favored the creation of the Second Back of the United States in 1816), and internal improvements (building of canals, roads, dredging harbors, etc.). During Clay's time, internal improvements (or what we today call infrastructure) was done at the state and local levels. The federal government didn't think it had the authorization to do such things. In 1816, in the waning days of his administration, President James Madison had asked Clay for an internal improvement bill. Clay fought hard opposition to get such a bill through the House and Senate. On a night where he had been invited over to the Octagon House (where President and Mrs. Madison lived after the British burned the White House in 1814), the president informed Clay that he was going to veto the infrastructure bill that had been sent to him on the grounds that he felt it violated the US Constitution. Despite that setback, Clay continued to be a voice for internal improvements over the decades to come. He ran on the issue in the 1824, 1832, and 1844 presidential elections. The biggest infrastructure project that would get passed from Clay's American System was the Cumberland Road.

A fight over internal improvements (or infrastructure) seems oddly familiar during this election year. In fact, it sounds oddly familiar over the last four years. Democrats in Congress have wanted to fund fixing our crumbling infrastructure while Republicans have balked at the idea... mainly on the cost and needing it to be offset by cuts elsewhere in the budget. Certain infrastructure projects, usually referred to as "shovel ready" projects, were a part of President Obama's 2009 stimulus package which aimed at putting Americans back to work as quickly as possible. But regardless of the stimulus package, America's aging infrastructure is crumbling at an alarming rate.

What has me on this particular topic is a recent column in Governing magazine by Alex Marshall. In his column, Mr. Marshall says the US doesn't invest in major infrastructure projects like it once did and is being passed by other nations (i.e. the Chunnel between Great Britain and France, the Oreseund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, and the Gotthard rail tunnel, etc.). While this may be the case since the United States has been investing in massive infrastructure projects for most of the 20th century (i.e. the Golden Gate Bridge, the Overseas Highway through the Florida Keys, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge between Staten Island and Long Island, the Hoover Dam, etc.), it doesn't mean that we are necessarily "being passed up". Continuing on from that, Mr. Marshall claims that we should be spending more money on giant infrastructure projects to recapture the American spirit and put people back work. And though I don't disagree with Mr. Marshall's idea of recapturing some pride in our country and getting people back to work, I don't think adding to our current infrastructure is the answer. He's close to it though. Instead of investing in new infrastructure on such a grand scale (which still happens from time to time), we should be investing the majority of that money in rehabbing our infrastructure that is already in place.

What has me on this particular topic is a recent column in Governing magazine by Alex Marshall. In his column, Mr. Marshall says the US doesn't invest in major infrastructure projects like it once did and is being passed by other nations (i.e. the Chunnel between Great Britain and France, the Oreseund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden, and the Gotthard rail tunnel, etc.). While this may be the case since the United States has been investing in massive infrastructure projects for most of the 20th century (i.e. the Golden Gate Bridge, the Overseas Highway through the Florida Keys, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge between Staten Island and Long Island, the Hoover Dam, etc.), it doesn't mean that we are necessarily "being passed up". Continuing on from that, Mr. Marshall claims that we should be spending more money on giant infrastructure projects to recapture the American spirit and put people back work. And though I don't disagree with Mr. Marshall's idea of recapturing some pride in our country and getting people back to work, I don't think adding to our current infrastructure is the answer. He's close to it though. Instead of investing in new infrastructure on such a grand scale (which still happens from time to time), we should be investing the majority of that money in rehabbing our infrastructure that is already in place.

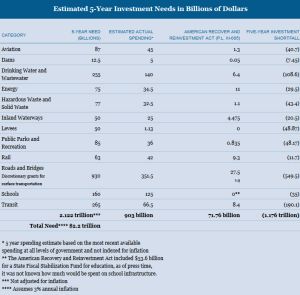

On August 1, 2007, the westbound I-35 bridge in Minneapolis collapsed into the Mississippi River. An investigation concluded that a design flaw and extra weight from equipment on the bridge surface for repairs were to blame. According to the Federal Highway Administration (US Department of Transportation), there were 143,889 deficient bridges in the US... out of a total of 605,086). That is almost 25%. In 2007, there were 4,095 deficient dams in the country. Of that, 1,826 of those dams were considered high-hazard deficient dams (83 of which were repaired with another 1,743 of them needing repaired). And this still doesn't include rivers, harbors, and other waterways that need to be dredged, repairing railway lines, and resurfacing roadways from our state and national highways to the interstates. I shall put a little local twist to this part. Missouri has a high percentage of deficient bridges. The newest bridge coming into downtown St. Louis from the Illinois side is the Poplar Street Bridge which was built in the late 1960s and carries three interstates across it (I-70, I-55, and I-64). It is of the same design as the I-35 bridge in Minneapolis. Soon, after all of these decades, there will be a brand new bridge entering the city of St. Louis, the I-70 bridge... which will move that interstate from the Poplar Street Bridge to the new one and hopefully alleviate traffic. For two years, 2009 and 2010, stretches of I-64 were shut down in St. Louis County and St. Louis City for removal of all the overpasses over and under I-64 and for a complete rehab of the highway. The city has also used funds from the 2009 stimulus bill to remove and rebuild overpasses over I-55 and I-70. The interstates and the overpasses had been built in the 1960s and were in desperate need of repairs. I would imagine that St. Louis is not alone in that category, and that most cities have the same types of crumbling infrastructure. (NOTE: The Eads Bridge, the oldest bridge to span the Mississippi River is about to undergo a major rehab to ensure that it stays around. At the time of its construction, it was a major engineering marvel.)

If rivers, canals, and harbors aren't constantly dredged, they fill up with silt. How does that help commerce between various ports in our own country and for trade with out countries? The southern half of the Intracoastal Waterway which runs up the Atlantic coast is filling up with silt because it's not dredged as much as the northern-half. The concept of such a waterway can be traced back to Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin in 1807, but didn't really get going until the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1909 and 1910. From the years 1910-1914, the navigation channels were deepened. The Intracoastal Waterway also proved useful during wartime as it protected ships traveling the coast from enemy subs and the water was a lot smoother for sailing than being out on the open ocean. Even the mighty Mississippi River has to be continuously dredged so that river traffic is not impeded. It is still the great inner-continental "roadway" linking various ports in roughly 2/3rds of the US.

Earlier, the number of deficient dams were listed as provided by the Infrastructure Report Card. Throughout parts of Kentucky and Tennessee (where dams were part of the Tennessee Valley Authority... part of President Roosevelt's New Deal), and especially up in the Pacific Northwest, these dams are a vital source of life. They create tourist destinations, provide water to communities, help with flood control, and assist river navigation. If one dam were to crumble enough to let out the enormous amount of water held behind it, the people and towns downstream would be devastated. On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam suffered a catastrophic failure releasing 20-million tons of water racing downstream toward Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The flood killed more than 2200 people and caused more than $17-million in damage. Many of our dams and bridges were built as part of the New Deal during the 30s and 40s. Most weren't designed to last this long. They are in constant need of repair so that they can continue to hold back the enormous amount of pressure that is pressing up against their walls. One could only imagine what a catastrophic failure would cost in today's money and in lives... especially if the wall of water hit a major population area.

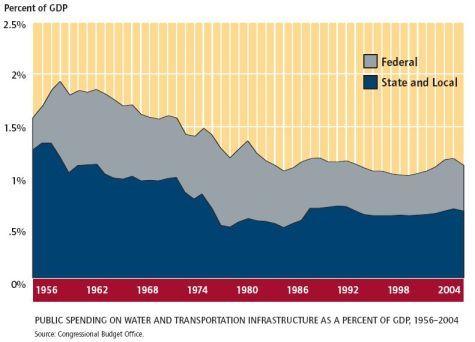

Over the last few decades, money spent on infrastructure has fallen both at the federal and the state level. Even now, talks have stalled in Washington between the House and Senate versions of a new federal transportation bill. (The Hill) This would include funding for both new projects and current projects... both for building new and for rehabbing old. So while I do agree with Mr. Marshall's claim that we need to be investing in infrastructure in our nation, I believe that it's not the right time to be seeking on a lot of huge projects but rather to rehabbing what we already have. He talked about all the great things we have built on in our past, and they still do stand as a great example to American ingenuity. There will still be those types of projects, even if they aren't as numerous as they once were. But part of that American ingenuity (or American pride) should be the upkeep of those projects. If we are proud of them, then we should be willing to make sure that they are around for generations to come. The legacy of those great projects isn't just what they accomplished, but their longevity. As I continue reading about Henry Clay, I must wonder what he would think about all of our internal improvements that we have today... his American System come true. He fought his entire political life for such things with only minor victories, but now we see it as commonplace for the federal government to take the lead on such projects.

Over the last few decades, money spent on infrastructure has fallen both at the federal and the state level. Even now, talks have stalled in Washington between the House and Senate versions of a new federal transportation bill. (The Hill) This would include funding for both new projects and current projects... both for building new and for rehabbing old. So while I do agree with Mr. Marshall's claim that we need to be investing in infrastructure in our nation, I believe that it's not the right time to be seeking on a lot of huge projects but rather to rehabbing what we already have. He talked about all the great things we have built on in our past, and they still do stand as a great example to American ingenuity. There will still be those types of projects, even if they aren't as numerous as they once were. But part of that American ingenuity (or American pride) should be the upkeep of those projects. If we are proud of them, then we should be willing to make sure that they are around for generations to come. The legacy of those great projects isn't just what they accomplished, but their longevity. As I continue reading about Henry Clay, I must wonder what he would think about all of our internal improvements that we have today... his American System come true. He fought his entire political life for such things with only minor victories, but now we see it as commonplace for the federal government to take the lead on such projects.

LINKS:

Henry Clay: The Essential American

Five Biggest Infrastructure Projects - Governing