How Californians Without Solar Got Stuck Paying for Those Who Do

Californians pay the second-highest electricity rates in the nation, more than double the U.S. average, and those rates are climbing faster than inflation and rising more quickly than in almost every other state.

At the heart of the problem is a little-known state policy operating as a reverse Robin Hood, a system that favors those who can afford to own homes and outfit them with rooftop solar panels — while forcing everyone else, especially renters, to foot the bill.

The program at the center of this debate is called Net Energy Metering, or NEM.

Created in the 1990s, its original purpose was straightforward and well-intentioned: to encourage people to invest in clean energy by letting them sell excess solar power they generate from rooftop solar back to the grid at full retail rates. At the time, it was hailed as a smart way to jumpstart California’s renewable future.

And in many ways, it worked. California today has among the highest rates of rooftop solar adoption in the country, with more than 1.6 million households using the program. But as adoption grew, so did the hidden costs.

The “Solar Cost Shift”

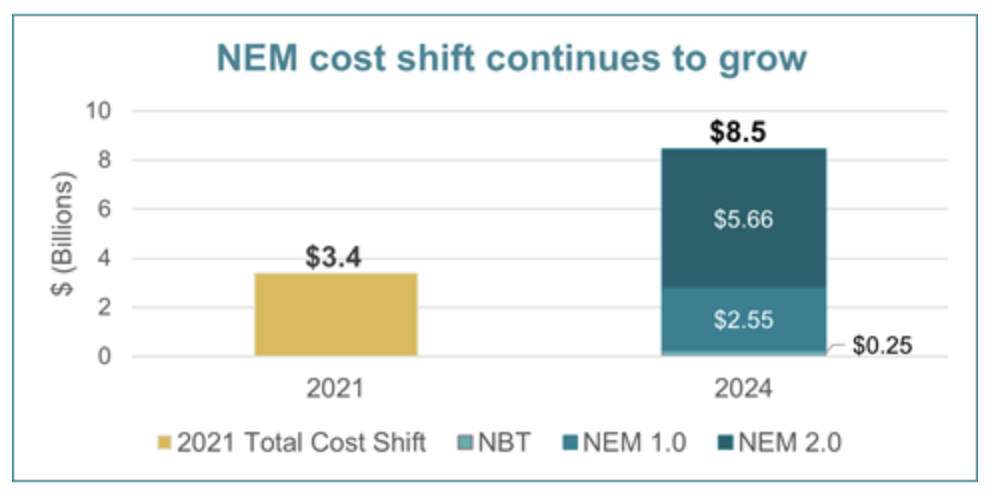

According to the California Public Advocates Office, the cost of NEM to non-solar customers reached $8.5 billion in 2024, more than double the $3.4 billion cost just three years earlier.

California’s main rooftop solar incentive program (known as net energy metering or NEM) will cost customers without solar an estimated $8.5 billion by the end of 2024, a figure that has more than doubled since 2021. The recent cost increases are driven by: (1) a surge in interconnections of new rooftop solar systems prior to the phase out of unsustainable program compensation terms, and (2) higher compensation to rooftop solar customers for the energy their systems generate.”

Roughly 10 million Californians without rooftop solar now pay as much as 27 percent more on their electricity bills to subsidize those who do.

“The rates that residential customers pay can vary widely,” the Legislative Analyst’s Office explained in a January 2025 report. “This is largely due to California’s relatively robust cost-reduction programs for low-income households and rooftop solar customers, which are subsidized by other ratepayers who do not qualify for those discounts.”

California “has not required solar customers to pay for their full share of the fixed costs of the electricity system.” Instead, “some of this cost burden has been shifted to other customers (often referred to as the solar cost shift).”

That solar cost shift is now one of the single most significant drivers of California’s high electricity prices, according to the Public Advocate:

In general, the customers who are purchasing less electricity are those who own their homes and can afford to buy or lease rooftop solar panels and in-home battery storage. On that basis, we know that advantaged customers are paying less fixed and operational costs while disadvantaged customers are paying more.”

A recent study found that it makes up 14.2 percent of the average residential bill for customers of PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric. That exceeds the share allocated for wildfire mitigation and renewable energy requirements.

How It Really Works

The imbalance stems from how rooftop solar users are compensated. Most receive bill credits at or near the full retail price for every kilowatt-hour they export, even though the actual value of that electricity to the grid is far lower. Utilities might pay 5 or 6 cents per kilowatt-hour on the open market, but are required to compensate solar customers 30 to 40 cents, even during hours of the day when demand is low.

Tom Philp, in an op-ed for the Sacramento Bee, described the distortion this way: “The rub is that these payments are regulated to be way beyond the market price for power, akin to being forced to buy gasoline at $20 a gallon. Lowering these rooftop solar power payments would lower the costs to the utilities, and in turn, the bills to ratepayers.”

The financial advantage does not stop there. Because solar customers use less electricity from the grid, they also contribute less to fixed infrastructure costs, such as transmission lines, wildfire safety upgrades, and subsidies for low-income households. Those costs do not disappear, so utilities are forced to recover them by raising rates on everyone else.

Solar customers in California have historically received large credits for the electricity they generate, which has shifted more of the burden for covering fixed costs to and correspondingly raised rates for nonsolar customers…CPUC estimates that solar cost shifts contributed between 11 percent and 20 percent to non-CARE non-solar customers' bills in 2023, up from between 8 percent and 17 percent just a year earlier.”

Who Pays and Who Benefits

The equity implications are stark. Research by UC Berkeley economist Severin Borenstein shows that households adopting solar are disproportionately higher-income and white, while the people paying the added costs are more likely to be renters, seniors, and lower-income families.

“In California, households installing solar are disproportionately wealthy (as well as disproportionately white), so the result is clear: Net energy metering shifts costs onto the poor,” Borenstein said.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office noted that from 2019 to 2023, electricity rates for the state’s three major investor-owned utilities — PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E — rose by between 48 percent and 67 percent. In inland regions like the Central Valley and the High Desert, where renters are more common and incomes are lower, families now spend 10 percent or more of their income on electricity.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, one of California’s strongest clean energy advocates, has also acknowledged the problem in a March 2025 report:

The evidence is clear that currently NEM has a large impact on rates that is mostly borne by renters, lower-income customers, and inland customers. Per our analysis, NEM is responsible for an increase of approximately $0.07 per kWh, or around 16 percent of the total residential retail rate today; $0.05 per kWh of this increase has occurred since 2018.”

A Growing Burden

The scale of the imbalance is accelerating. Solar adoption has soared in the last decade, especially in suburban and coastal communities. Between 2014 and 2024, rooftop solar capacity more than quadrupled. At the same time, the economics have tilted even further in favor of solar adopters. The payback period for a new system has shrunk to just four or five years, while subsidies last up to 20 years. That means homeowners can pocket the benefits for 15 years after they have already recouped their costs, and the benefits are paid for by everyone else.

The Court Fight

The controversy has spilled into the courts. In 2023, a coalition of rooftop solar companies and environmental groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity, filed a lawsuit challenging the California Public Utilities Commission’s latest reforms to address the inequities.

The CPUC attempted to update the system by introducing the “Net Billing Tariff” for new customers, which ties compensation more closely to the actual market value of electricity. But the new rules do not apply to the 1.6 million households already grandfathered into NEM 1.0 and 2.0.

The lawsuit argues that even these modest changes go too far and threaten the rooftop solar industry. Consumer advocates concerned with skyrocketing rates counter that the reforms do not go far enough, since the old, highly favorable subsidies will remain in place for up to two more decades.

The legal battle has become a proxy fight over whether the state will prioritize maintaining incentives for rooftop solar or reining in the costs for the millions of Californians without it.

Sacramento’s Response

In the legislature, there have been attempts to address the imbalance. Assemblymember Lisa Calderon (D-Whittier) introduced AB 942 with coauthor Senator Bob Archuleta (D-Pico Rivera), a bill that would reduce but not eliminate the subsidies for solar customers. In Calderon’s district, an estimated 92 percent of constituents do not have rooftop solar, meaning they are stuck subsidizing the other 8 percent.

The bill proposes to preserve most of the subsidies — between 76 and 82 percent of current levels — while providing some relief to non-solar customers. But it immediately drew fierce opposition from the solar industry, which accused lawmakers of breaking contracts and handing profits to utility companies.

Consumer advocates dismissed those claims. The NEM tariff is not a contract, they noted, but a rate structure established by regulators. And utilities would not directly profit from the changes; customers would.

“Vilifying utilities is a clever strategy,” said Borenstein of UC Berkeley.

But the loudest calls for ending the current net energy metering system are coming from the leading consumer advocate organizations: The Utility Reform Network and the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office. The Natural Resources Defense Council is also on board, in large part because of the equity issues.”

On April 30, labor organizations and ratepayer advocates joined in support AB 942, which passed the Assembly Committee on Utilities and Energy by a vote of 10-5.

Calderon’s office estimated that AB 942 will save Californians $423 million in 2026 and $3.6 billion between now and 2043.

“Solar power is an important part of our state’s renewable energy grid, but we have to reevaluate how our current solar subsidy programs impact Californians who may not be able to afford solar-panel systems,” said Calderon.

Our energy bills are becoming increasingly unaffordable, and we must address this ratepayer inequity.”

On August 18, AB 942 passed the Senate Appropriations committee by a 7-0 vote, with Senators Cabaldon, Caballero, Dahle, Grayson, Richardson, Seyarto, and Wahab voting yes.

What Comes Next

The CPUC’s Net Billing Tariff only applies to new solar customers. At the same time, the 1.6 million households already enrolled in earlier NEM programs will continue receiving premium subsidies for up to 20 years if the bill doesn’t pass. That means the cost shift is likely to grow larger before it shrinks.

Critics of the system argue that reform is overdue, not to punish solar adopters, but to modernize an outdated policy that has veered far from its original purpose. NEM was designed to make solar accessible at a time when it was rare.

Today, it has created a two-tiered system where those who were able to afford to buy into the program will be rewarded for decades, while those who could not are left with soaring bills.

California’s solar divide reveals an inconvenient truth about clean energy policy. Even well-intentioned incentives can create hidden inequities if left unchanged for too long. And as long as the current system remains in place, renters and lower-income Californians will continue subsidizing their wealthier, solar-equipped neighbors.

Cara Brown McCormick

Cara Brown McCormick