Why Gallup May Be Wrong About Voter Turnout in 2014

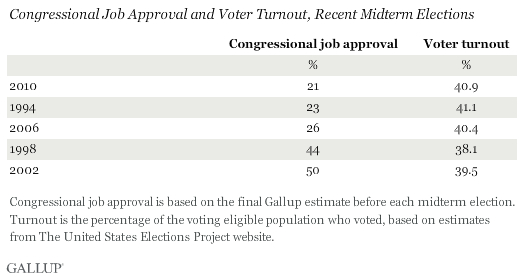

On Monday, August 25, Gallup published a report on why a historic-low congressional approval rating could result in an increase in voter turnout in November. According to Gallup, there is a correlation between lower congressional approval and higher voter turnout, looking at midterm elections dating back to 1994.

Gallup currently has congressional approval at 13 percent, which would be the lowest approval rating in a midterm election. In fact, only 19 percent of Americans think most members of Congress should be re-elected. And perhaps for the first time in modern U.S. history, a plurality of Americans don't approve of the job their own representative is doing.

If Gallup's hypothesis about voter turnout is correct, these three things combined should boost voter turnout in the general election by a notable degree.

Between 1994 and 2010, voter turnout ranged from 38.1 percent and 41.1 percent. The highest turnout was in 1994 when Republicans took control of both chambers of Congress and congressional approval was at 23 percent. In 2002, when congressional approval was at 50 percent, nationwide turnout during the general election was 39.5 percent.

Looking at it from this perspective, Gallup certainly has numbers to support its hypothesis.

However, interestingly enough, the next highest turnout (40.9 percent) was in 2010 when Republicans once again took control of the House of Representatives (but didn't acquire the Senate). Congressional approval at the time of the election was at 21 percent. The approval rating and voter turnout were both slightly lower than they were in 1994.

Between 1998 and 2002, both the congressional approval rating and voter turnout increased. In fact, congressional approval jumped from 44 percent to 50 percent before plummeting again ahead of the 2006 election.Between 2006 and 2010, voter turnout rose from 40.4 percent to 40.9 percent. That isn't much of an increase and 2010 was when conservative grassroots mobilization was at its peak with the rise of the tea party.

Gallup could just as easily make the case that voter turnout in 2014 could be higher because voter turnout in congressional elections has risen slightly every midterm election since 1998. It is another correlation between the two figures, but that is all Gallup is looking at -- correlations, not causation.

To the polling group's credit, it does acknowledge that voter turnout may not rise depending on voter perception:

"If many voters see little possibility of changing the partisan makeup of government after this fall's elections -- given that a divided government is already in place and almost certainly will be after the elections -- there could be no increase in turnout this year despite Americans' frustration with Congress."

What happens when a majority of Americans no longer feel either major party represents America? What happens when Americans are so disenchanted by a system that has produced hyperpartisanship, they don't believe their vote matters anymore? What happens when after several election cycles of thinking they can change government for the better, voters realize that the system is rigged to maintain the status quo?

Instead of examining possible correlations, we need to start asking the right questions to determine the cause of low turnout. Why, in two decades, have we not seen a voter turnout in a midterm election higher than 41.1 percent?Gallup argues that when voters feel more empowered to change the makeup of government, they are more likely to vote in greater numbers. I believe this to be true as there is evidence to support it. In 2008, voter turnout broke records in states across the country because the masses were drawn in by the promise of "hope and change."

The sad truth, however, is that a majority of Americans -- even in the midterm elections with the highest turnouts -- don't seem to feel empowered by the current election system. Instead of looking at the 40.9 percent of the electorate who did vote in 2010, why don't we take a closer look at the 59.1 percent who didn't.

Photo Credit: Tanarch / shutterstock.com