Primaries: A Major Party Failure Is A Third Party Opportunity

Let’s be clear here. Major-party primaries in the US are absurd.

Parties in most countries select their nominees privately and pay for it on their own dime. That’s not surprising either considering that political parties are private organizations.

In the US, however, parties do their primaries publicly. That may sound nice, but as private organizations, US parties get to make their own rules. These rules conveniently include who gets to vote and how those votes are counted.

The benefits to major parties don’t end there. In addition to controlling their primary rules, these private political parties regularly get to hand taxpayers the bill.

Take a look at the DNC. A poll by the Associated Press targeting superdelegates showed Clinton starting out with a 359 to 8 lead against Sanders. That’s the count before regular people like you and me even saw a ballot. This predetermined outcome overturned a Sanders win in New Hampshire. The two camps got the same number of delegates despite Sanders winning by 22 percentage points in the state’s popular vote.

The DNC leadership has been clear on this. Current DNC Chair Wasserman Schultz said, “Unpledged delegates exist really to make sure that party leaders and elected officials don’t have to be in a position where they are running against grassroots activists.“

Howard Dean, a superdelegate himself and former DNC chair, agreed, “Superdelegates don't ‘represent people’. I'm not elected by anyone.”

The RNC has its own issues with voters, though superdelegates appear not to be among them. According to Virginia Republican National Committeeman Morton Blackwell, state delegates are indeed bound to vote according to the state’s popular vote, but only on the first ballot. Now, if no candidate is able to get the requisite number of delegates in the first round, then all bets are off for subsequent ballots.

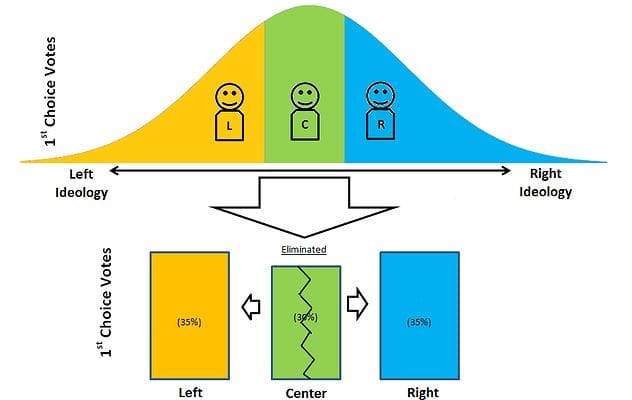

The Republicans’ issue this year has been vote splitting—that is, votes dividing between candidates that have similarities. Vote splitting is caused by Republicans using our awful, choose-one voting method — plurality voting. Plurality’s vote splitting particularly hurts candidates perceived by the electorate as moderates because of something called the “center squeeze” effect. Under the “center squeeze” effect,” the vote splits to either side of the moderate candidates, whereas extreme candidates have their vote divided on only one side. This helps a more polarizing candidate like Trump—whose own party finds his positions so extreme that they make not-so-subtle statements disavowing his rhetoric.

The Democratic Party has avoided vote splitting for the duration of its primaries due to its lack of candidates—or at least a lack of willingness to recognize candidates. Harvard law professor and campaign finance reform advocate Lawrence Lessig, for instance, was able to raise an early one million dollars, but the DNC still refused to acknowledge him. This is just another instance of a major party reminding voters that they aren’t in control of their options.

But all this is from the major parties. The US—believe it or not—has more than two parties. Those other parties just have trouble getting elected under our current system. Third parties also have their own nomination process. And their nomination process can have eerie similarities to the major parties, which includes using delegates. At least, however, not every third party has opted for our awful, choose-one voting method.

For instance, the Texas Green Party uses approval voting, which lets you choose as many candidates as you want. Using approval voting sidesteps vote splitting and favors more moderate winners (moderate to those voting). The Texas Libertarian Party has been using approval voting to fill other nomination spots. And many other Green Party states use a more complicated ranking method, instant runoff voting—which is still better than our terribly awful, choose-one voting method.

The major parties may be in the beginnings of catching on. A Republican caucus in Colorado provisionally used approval voting in the 2016 election for presidential nominations and then recommended it for the state level. The party at the state level was not responsive, however.

For the moment though, let’s just assume the major parties are too stuck in their ways to innovate.

Remember that third parties use a delegate system as well. And they can encounter some of the same obstacles, even though they don’t use protectionist measures like superdelegates.

Here are some of the issues with using delegates. First, you have to figure out how to assign the number of delegates to each state. And by its nature, some states will get an unfair advantage here, in the same way that the smallest populated US states get an unfair advantage with electoral votes—which very much violates the equal weight rule of one person, one vote. For instance, a presidential vote in Wyoming has the weight equivalent of close to two Montana votes. The same unfairness is happening in party primaries.

On top of that, every state has to deal with rounding errors when assigning those delegates to candidates. Even when delegates are allocated in proportion to the vote, the real world doesn’t deliver votes with perfect common factors. And that rounding can change the outcome in a close election.

All this delegate assignment is complicated. You have to deal with all these rounding and apportionment issues. So why do third parties use delegates at all?

Here, it gets a little tricky. Some third parties get to participate within the state’s primaries. Other times they do caucuses or conventions. But caucus and convention voter turnout is much lower than the primary voter turnout for an entire state. That means we can’t just use a straight popular vote because caucus and convention states would be at a severe disadvantage.

So now what?

Let’s get the easy part out of the way. We’re not using the worst voting method there is—plurality voting. We’ll use approval voting instead by letting voters choose all the candidates they want. It’s easy, flexible, and addresses vote splitting.

Approval voting also has a precinct summability feature. That means you can sum vote totals in precincts and states and then add those totals together. You don’t need a central tabulation point like you do with popular ranking methods such as instant runoff voting.

Now what is our goal here? We’re assigning states the same weight as they are now, which is according to population. We also want to make voter turnout irrelevant because some states use traditional primaries and others don’t. Party membership turns out to be challenging to determine in practice, particularly for third parties, so we have to ignore that as a factor.

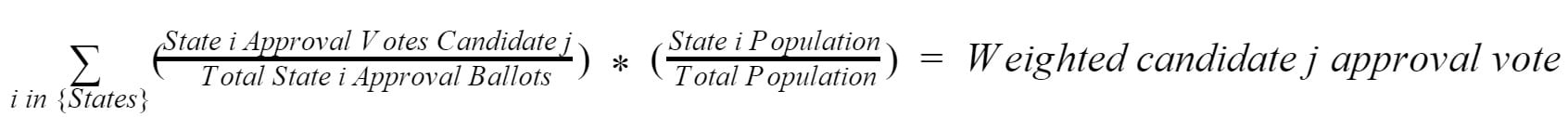

So this is what we do for each candidate in each state:

All this means is that we take a candidate’s approval vote percentage and give it a weight according to the state population where the votes came from. And then we repeat that for every state and for every candidate. States would just send their vote totals and number of ballots to the national party site. The national party site would do all the reweighing to avoid complexity at the state level. All this can be done transparently.

So if third parties want to upgrade their primaries, they can both avoid vote splitting and approximate the outcome of a national popular vote. And they can do all this without the crude rounding and apportionment issues. They wouldn’t even have to worry about whether a state (or other constituency) uses a caucus, conventions, or traditional primary. That’s because this approach works without respect to voter turnout.

Best of all, third parties using this would have a fair nomination process that is more reflective of one person, one vote where everyone’s ballot has the same weight. And their final nomination would be a strong party candidate given those running. Approval voting also makes running many candidates convenient, which means it allows for races with healthy competition.

This is a win and advantage for third parties. As major parties persist with their odd primaries, third parties can have something to gloat about by using a process that is simpler, fairer, and—best of all—more effective.

Editor's note: This article originally published on The Center for Election Science's blog and has been modified slightly for publication on IVN.