The Strengths and Weaknesses of 3 Proportional Voting Methods

There are three methods of proportional representation advocates most commonly present: cumulative voting, limited voting, and ranked-choice voting. Each has been used in the United States, mainly in local and county elections, with decent success.

The first two systems only simulate proportional voting while ranked-choice can fully incorporate proportional voting.

Cumulative voting is a system used in multi-seat elections where the voter is given a number of ballots equal to the number of seats being elected. The voter can then, in turn, allocate these ballots as they see fit.For example, in the Kansas congressional elections, there are four seats up for grabs with nine candidates running in November. Each voter would be given four ballots. Voters could give all four of the seats to one candidate or could spread the ballots out through any number of combinations.

The Amarillo Independent School District in Texas is the largest jurisdiction in the nation to use cumulative voting. Prior to instituting the voting method, there had not been a minority member of the school board since the 1970s -- even though the total population was 22 percent minority (16 percent Latino, 6 percent African-American).

After the first two election cycles with cumulative voting (2000 & 2002), the school board featured two Latino members, and one African-American. Forty-three percent of the seats were held by minority representatives -- considerably larger than the demographics of the population at large.

The single greatest advantage to cumulative voting is that voters can specifically emphasize their preferences by giving candidates more than one vote.

There are several disadvantages to this system:

- It is not a true proportional voting system as demonstrated by the over-representation of minority school board members in the 2000-2002 elections in Amarillo.

- It requires huge amounts of political party involvement to ensure that the voting blocs stay in lock-step.

- Political parties have to "self-regulate" the number of candidates vying for the election -- too many candidates from any one party has the potential to dilute the vote (i.e. the party receives the most ballots, but no individual candidate receives enough votes to win a seat).

- It would be unlikely for minor-party or independent campaigns to be able to organize sufficiently to capture a significant portion of the vote.

- Perpetuates the false paradigm that all independent or minority campaigns are representative of an entire bloc of voters. For example, Ben Carson and Barack Obama are both African-American males. However, regardless of the demographic groups they share, they are polar extremes politically. Neither one could possibly represent the entire African-American voting bloc. This creates a false sense of diversity and proportionality.

The first statewide usage of cumulative voting was in the Illinois House beginning in 1870. Party collusion and less-than-full slates became the norm -- although it did have the effect of diversifying the makeup of the Illinois House.

In the United States, limited voting is isolated to about two-dozen city councils in Alabama and a handful of school boards and county commissions in North Carolina.

The strength of this system is that it is almost impossible for there to be a "sweep" by the majority party on election day -- the mathematics of the system almost totally ensure at least some representation by one or more minority parties (assuming the parties run a full slate of candidates).

Limited voting is much like cumulative voting in that voters are given multiple ballots. But, the number of ballots is less than the number of seats.

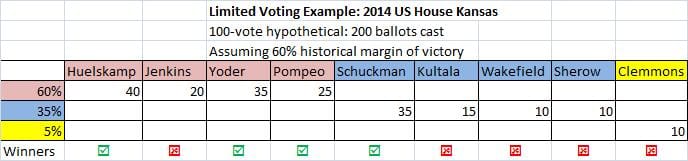

In the Kansas U.S. House example, with four seats available, each voter could be given 2 ballots (or any number less than four). The 2014 Kansas congressional election could end somewhat like this hypothetical:

This hypothetical highlights the weakness of the limited voting system. In this example, the expected majority party (Republicans) conduct a "business as usual" election -- nothing special.The minority party (Democrats) have to actually use considerable strategy to win a seat. If the ballots were evenly divided among the Democratic candidates, the Republicans would win all four seats.

To ensure winning a seat, minority party officials would have to endorse a specific candidate as "the one" to vote for in the election so that this candidate would meet the winning threshold. The Libertarians have no impact on the race other than that of "spoiler."

The major parties end up having more control over selecting who is elected than the voters, especially when the minority party is trying to win a seat.

Even worse, in this example, the minority party could have theoretically won half of the seats if the entire party voted as a bloc -- this is hardly a true system of proportional representation, but a system highlighting the dangers of bloc voting.

To ensure victory under this system, the majority party has to concede a portion of the seats (in this example, one seat). If the majority party tries to win all of the seats, it opens the door to the minority party winning more seats than "they should."

So, this system winds up with the majority party throwing one of their own "under the bus," while the minority party has to figure out how to convince their bloc to support only one of their ranks.

Like cumulative voting, the political parties will usually have to resort to less-than-full slates for the election to ensure that party members remain in lock-step with the leadership's decision.

This sounds a bit too much like cronyism and back-room deals, and is still a fundamentally "two-party solution" that ignores independent and third-party campaigns.

Ranked-choice voting, along with instant runoff voting (its single-seat form), represent a system where candidates are elected with ballots that rank the candidates by voter preference. Outright winners can be determined by first choice, but are most often decided by second and third choices.Ranked-choice and instant runoff voting are used throughout the world and in many municipalities in the United States.

Once a candidate has crossed the threshold to win (determined by the number of seats available), that candidate's excess votes are transferred to the voter's next choice.

Ranked-choice voting on the surface is the most complicated of the proportional voting systems. Yet, it is simplistic in nature because it is how humans see the world. We naturally perceive "better than" and "worse than" in our daily thought processes.

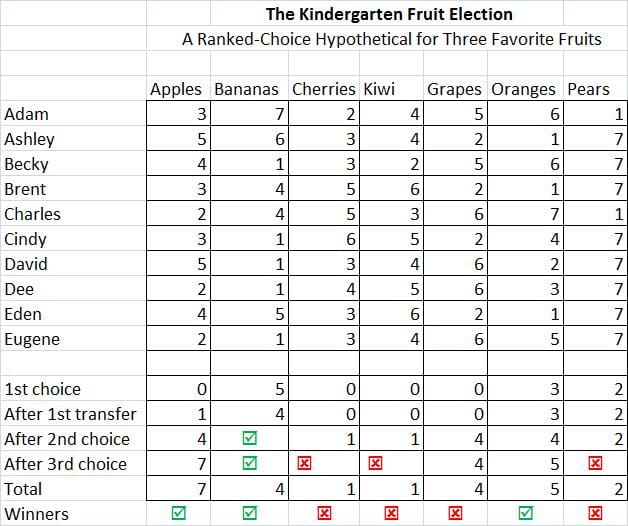

If a bowl containing seven different fruits was placed in front of a group of kindergartners -- with very little explanation -- the group members could rank them in order of preference:

In this example, Bananas are a clear first-choice winner -- capturing 50 percent of the first-choice votes. For simplicity, using a 1/3 threshold to win (in whole votes), part of Bananas' vote is transferred to the next choice. In the second-choice round, three more candidates meet the election threshold by the same amount, forcing a third-choice round of voting to eliminate one of the candidates.

The strength in this example (which obviously won't hold in every single case) is that every voter is represented -- even when the voter "throws away" their first-choice vote on a candidate that is unlikely to win.

There are multiple ways of counting the ballots -- or assigning the winning threshold. This example was designed with simplicity in mind. Some work backwards, starting with the mathematically eliminated candidates and transferring the votes according to voter preference until winners are determined. Some work by eliminating a candidate after every round, and transferring their ballots.

The weakness to ranked-choice voting is that "clean-sweep" party victories are possible unless a system of proportional outcomes is also implemented.

Our generation's perspective on third parties has been completely tainted by the 1992 presidential election. Bill Clinton's less-than-majority win has been largely portrayed (especially by conservatives) as a result of Ross Perot siphoning off votes that would have otherwise gone to George Bush.

Both political parties have used the "spoiler effect" to their advantage, maintaining that party loyalty prevents spoilers. The 2014 Republican primary campaigns are the result -- where the "unified" party is locked into heated primary battles fought over large ideological gaps.

With ranked-choice, independent and third-party campaigns have a realistic chance because broad appeal, not party politics, determines the winners. Voters can vote for their true preferences without feeling like they are undermining their party's chances at winning.

This is probably the single best advantage to ranked-choice voting: the general election and the primaries are all contested at the same time, on the same ballot.

Not only does this save the taxpayer costly primaries, but it expands voter choice -- multiparty voting becomes a viable option.

Ranked-choice is by far the best of the proportional voting methods. It completely solves most of the gerrymandering problems that exist, eliminates party "back-room" deals, and gives voters the largest manageable voting choices for each election. This could become the best thing that has happened to U.S. elections since the introduction of the secret ballot in the 1880s.

Editor's note: This is part three of a multi-part series examining proportional representation and the potential impact it could have on American politics. You can read part one here and part two here.