Accommodations, Exceptions, and the Post-Hobby-Lobby Contraception Mandate

In the world where I spend most of my life—the world of higher education administration—the difference between an accommodation and an exception could not be more important.

Accommodating students with specific needs is part of providing equal educational opportunity. Accommodations include such things as providing sign-language interpreters, note takers, recorded textbooks, and extra time on tests.

The guiding philosophy behind educational accommodations is that every student should have an equal opportunity to learn the material in a course and have that knowledge assessed by an instructor.

From time to time, educators are asked to forgo that philosophy and make exceptions for students who are having difficulty in a course — to require less reading, or fewer tests, or lower grades for some students than for others. Exceptions often look like accommodations, but they are actually very much the opposite.

Exceptions change the nature of an education. And educators who mistake exceptions for accommodations risk destroying the very educational standards that they exist to promulgate.

While accommodations help students learn, exceptions virtually ensure that they do not learn. Accommodations support, while exceptions destroy, the integrity of the enterprise that creates them.

While these terms work somewhat differently in constitutional law than they do in educational administration, the overall principles are — as the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision shows -- very much the same.The logic of Burwell v. Hobby Lobby is the logic of accommodation.

Following the requirements of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the court determined that, even though the state might have a compelling interest in ensuring universal contraception coverage, this interest could be met in ways less burdensome to the religious practice of certain kinds of owners of corporations.

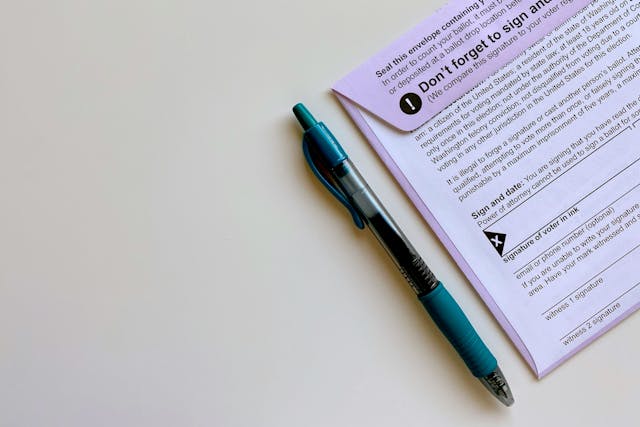

In fact, the necessary compromise was already in place, having been worked out by the Obama administration last year for religiously affiliated non-profits. The compromise was a clear accommodation. Organizations would not have to offer contraception as part of their insurance package, but insurance companies would be required to provide it at no cost to those who requested it.

Insurers happily went along with the compromise, knowing that, in the long run, plans that include contraception coverage are 15-17% less costly to them than plans that exclude it. This is because many of the things that contraception prevents — such as pregnancies, abortions, childbirths, and children — are much more costly than the contraception itself.

As long as the courts follow the logic of accommodation, then last week’s parade of horribles from the left will remain a partisan fantasy.

Religious accommodations cannot include, say forcing Sharia law on employees, or forbidding blood transfusions, or any of the other things that have temporarily replaced cat memes on my Facebook feed. Such things are not accommodations at all; they are exceptions.

But here is the problem: now that the court has created an accommodation, they are being asked to consider a multitude of exceptions, most notably the case of Wheaton College, a Christian school that is already exempt from providing contraception under the 2013 compromise but which now wants to prevent its female employees from even requesting such coverage independently.

Last week, a majority of the court agreed to grant Wheaton a temporary stay, saying that, until the issue was resolved, they did not have to fill out the form to indicate their religious objection to providing contraception -- occasioning a blisteringdissent from the three female justices authored by Justice Sonja Sotomayor.

"Those who are bound by our decisions usually believe they can take us at our word," wrote Sotomayor. "Not so today."

Justice Sotomayor’s argument in the dissent correctly identifies the shift in the Supreme Court’s reasoning from Monday to Thursday of last week. Monday’s Hobby Lobby decision was a religious accommodation — one that carefully acknowledged both the right of business owners to exercise their religion and the right of the state to set minimum standards for insurance coverage.

The Wheaton College case, and most of the hundred or so other cases currently lining up in the queue, seeks religious exceptions. These cases argue that the rights of religious employers should overrule insurance regulations, equal employment laws, and other federal guidelines for employers.

It will be tempting for the courts, and for Americans generally, to believe that religious exceptions proceed logically from religious accommodations. But they do not.

Accommodations and exceptions are fundamentally different kinds of things. One allows us to balance competing interests, while the other demands that we sacrifice one set of interests to another.

With the contraception mandate, (and anything else) one can certainly favor both of them, one of them, or none of them. But we should at least acknowledge that the logic of the one doesn't get us anywhere near the neighborhood of the other.