What Are the Different Types of Primary Elections?

Primaries first began in the early twentieth century as a response to increasingly strong party control over elections. At the time, voters wanted a larger say in who would be chosen as their candidate, instead of the long-standing tradition of party bosses choosing who would run for office. Progressive reformers viewed direct primaries as a way for constituencies to increase transparency and allow for citizens to participate in the electoral process. As primaries became a feature of local, state, and eventually national elections, each municipality had the ability to shape their own process.

Today, most systems fall under two broad categories: Partisan and Nonpartisan primaries, with variations falling under each. This article will provide a comprehensive examination of this pivotal first step in the election process.

Partisan Elections

Partisan primary elections are, by their very nature, elections which select a candidate based on their party affiliation. Most states have utilized a partisan primary for much of the nation’s history.

When primary elections became popular, what developed was a process in which each major political party held “mini-elections” prior to the general election to see who would represent their party. What differed in these mini-elections was generally who could participate — a standard that was set by each state. These processes include: closed, open (partisan), semi-closed, and partisan instant runoff voting (IRV).

Closed primary systems are only open to those that are registered with a major political party. Therefore, a Democrat may vote in the democratic primary, Republicans may vote in the republican primary, but unaffiliated, “decline-to-state,” and minor party voters are denied participation. While some groups have challenged closed primaries over the right to “not affiliate with any party,” courts have held that closed primaries are constitutional.States that have a closed primary include Delaware, Maine, Wyoming, New Jersey, New York, New Mexico, and Kentucky. wherein voters must claim association

almost a year before the actual vote. The affiliation requirement stems from one of the main difficulties of closed primaries: a fear that primaries could be "raided" by outsiders who might seek to influence the primary election so a weaker candidate ends up running against their preferred choice in the general election.

Closed primaries, however, vary in other states. In New Jersey, for example, voters can declare the day of an election. However, both systems of a closed primary have been challenged in the court. Plaintiffs claimed that the right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment should not be predicated on the voter giving up their right not to affiliate with a political party. The Supreme Court though has upheld the constitutionality of a closed primary to date.

The main difference between semi-closed and closed primaries is that semi-closed primaries allow a party to choose whether or not to allow non-members to vote. However, this system still requires voters not registered with one of the major parties to change party affiliation to participate in primary elections. Voters are often given an extended amount of time to change registration -- some states up to election day.

While some states require that all political parties have the same method, other states like Utah allow the party to pick their primary election process. Therefore, Republicans have a closed primary and Democrats open theirs up to non-Democrat voters. In Idaho, parties can select to open or close their primary, but voters are required to vote in the next election with that party affiliation.

Semi-closed primaries are lauded by some for "allowing" unaffiliated and minor party voters full participation in the political process. Some opponents, however, argue that allowing these constituencies to vote will dilute the preference of party members. Advocates of nonpartisan reform argue that requiring independent or third party voters to change their affiliation to participate violates their First Amendment right of non-association because their ability to participate is conditioned on the parties' 'permission'.

This means that political parties cannot prevent non-members from voting in their party elections and in many of these states, like Hawaii and Texas, voters do not have to declare their affiliation when they register to vote. Voters may select from the Republican or Democratic ballot and their choices are limited to that ballot.

Recently, the Democratic Party of Hawaii (DHP) challenged the open primary system in Hawaii, arguing that open primaries place a severe burden on its First Amendment right of association and the ability to “limit its association to people who share its views."

A federal district court ruled against the plaintiffs and upheld the state's primary system. While the DHP believes that crossover voting can spoil the candidate selection process of a private organization, the court said they filed a lawsuit only on the assumption that this could happen instead of presenting evidence that it was happening. The court could not make a ruling based on an assumption.

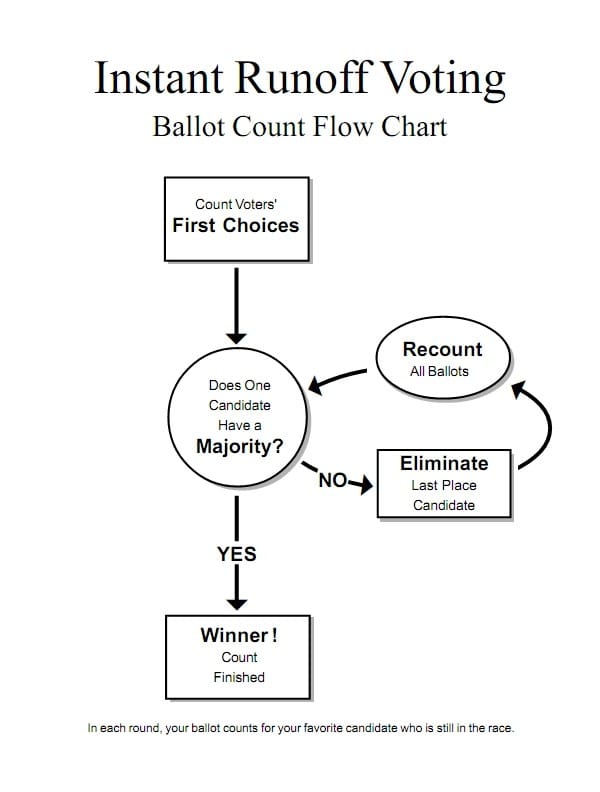

Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) is aimed at encouraging candidates to reach out to a broader constituency and can work in both partisan and nonpartisan elections. In this voting system, voters are allowed to rank candidates in order of preference. They are not required to rank all the candidates and their rankings will not harm their most preferred candidate at any stage. A series of automatic runoffs occur using voter preference.

Here is how IRV works:

if a majority is achieved on the first count, the election is over and the majority candidate wins outright. However, if that is not the case, the candidate who receives the fewest first choice rankings is eliminated. Then, all ballots are re-tabulated, with each ballot counting for one vote for the highest-ranked candidate who has not been eliminated. Therefore, voters who had the last place candidate now have their votes count toward their second choice. The weakest candidates are eliminated successively, with each new tabulation including their next choice that is listed. Once the field is reduced to two, the candidate with the majority will win the election.

Proponents of this system argue that it allows for better voter choice and wider participation by allowing multiple candidates in a race. However, some opponents argue that it doesn't allow for voters to fully weigh their choices -- arguing that a straight-up runoff in an election might allow less popular candidates an opportunity for greater exposure among the electorate and it would take time for the voters to make their decision.

A form of IRV was first used in 1912 in Florida, Indiana, Maryland, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The appeal of this system increased in the past two decades. Since 2000 alone, over 20 state legislatures considered bills that would implement IRV, including Maine, Alaska, Massachusetts, Illinois, New Jersey, Virginia, and Louisiana. Even the U.S. Congress introduced a bill to study this process in early 2003. Some cities, such as Minneapolis, Oakland, and San Francisco, allow instant runoff voting.

The process was most recently promoted in New York City after a separate runoff election in the Democratic primary for public advocate cost the city $13 million. After the election, which was both costly and had an extremely low voter turnout, legislation was introduced in the state legislature to implement IRV.

Nonpartisan Elections

Nonpartisan primaries operate as one election, where all voters and candidates participate on a single ballot. California, Washington state, and Louisiana are currently the only states to adopt some form of top-two system, but there are other types of nonpartisan reform that differ in the amount of candidates that move on to the second state of the election or add different voting systems -- like approval voting.

A top-two nonpartisan primary system, like the system in California and Washington state, is a two stage system where all candidates, regardless of party affiliation, appear on the same ballot. Parties do not hold their own primaries and if they do, it is done outside the public election system. The top two vote getters move on to the general election. Louisiana has a similar system, but if a candidate gets over 50 percent of the vote in the first stage, he or she wins the election outright.

Supporters of top-two primaries argue that not only does the system give equal access to the ballot for voters and candidates, it results in more robust competition, especially in districts that are purely dominated by one party.

Steve Peace, a former Democratic state legislator in California, authored the state's top-two initiative (Proposition 14) which was approved by voters in 2010. Peace believes this system helps politicians act in the state's best interest because candidates must appeal to a broader base of the electorate instead of a small, partisan base.

However, critics of the system in California lambasted top-two, claiming that the increased threshold to get on the ballot in the first place ensured that minor party and independent candidates had less of chance to appear on the general election ballot.

A top-four primary is another option for nonpartisan primaries, but it differs from top-two by increasing the amount of candidates that move on to the general election. During the first round of voting, the electorate votes for their first choice. The general election then has the names of the top four vote getters.If IRV is added in the general election, voters are allowed to place a first, second, and third choice. Each ballot then will count for the candidate marked for their first choice, but the candidate with the fewest first-choice preferences is eliminated. The ballots with those candidates are then placed into the pool for their second choice. The process is repeated again until there is a way to identify the top two choices. The candidate with the majority in that round is elected.

While nonpartisan primaries are increasingly being considered around the U.S., proposals are generally limited to the top-two process. Colorado, however, is proposing a more radical system that includes a variation of the top-four system.

The proposal would allow the top four candidates to advance, as well as anyone with 3 percent of the vote in the first round. Ryan Ross, who is the main force behind this new proposal, believes that this system would allow for multiple Democrats, multiple Republicans, and maybe some independents and third party candidates to advance to the general election.

A unified primary is a new system being proposed in Oregon to combine the top-two primary system with approval voting, which allows voters to select one or more candidates on the ballot, but does not use a ranking system. While only the top two vote getters will advance to the general election, approval voting ensures that the widest consensus of the population will support the candidates who advance to the final stage of the election.

The initiative is being spearheaded by entrepreneur Mark Frohnmayer, who argues that "compared to other primary systems, the ‘Unified Primary’ is less restrictive for voters because it does not limit them to selecting only one candidate in a field of many, and it does not limit them to selecting only from only one party’s candidates.”