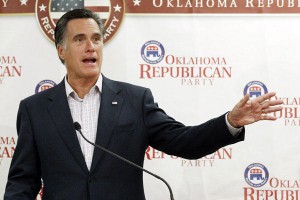

Mitt Romney's Candidacy Highlights Foreign Policy Struggles Within The GOP

The conservative base of the Republican Party was notoriously tepid in supporting front-runner Mitt Romney. But buried on page 16 of Thursday's New York Times, was a story suggesting that it's more than the party's conservatives who have dragged their feet to the Mitt Romney That Could.

Entitled "G.O.P. Foreign Policy Experts Slow to Back Romney," the Times reports that some doyens of Republican foreign policy have been reluctant to endorse the presumptive nominee.

Such eminences as former national security advisers Brent Scowcroft and Henry Kissinger have yet to endorse Romney while former secretary of state Colin Powell didn't even endorse John McCain in 2008. Powell is the only one unlikely to offer an endorsement, considering he recently chastised Romney for his characterization of Russia as America's #1 geostrategic threat by saying, "Come on Mitt - think."

According to the article, the fear among the old guard is mostly due to the neoconservative make-up of Romney's foreign policy team.

Scowcroft broke with his party and denounced the upcoming invasion of Iraq in a famous 2002 Wall Street Journal editorial while Powell regards Romney's advisers as "quite far to the right" although that only means Powell doesn't understand the terms.

At first, one might assume the neoconservative triumph in the Republican Party was already complete. To an extent this is true. Without the influence of the neoconservatives it's hard to gauge whether Bush would have invaded Iraq following the initial triumph in Afghanistan. But his second term, second inaugural notwithstanding, the Bush administration was noticeably more restrained.

Writing in the June issue of The American Conservative, Jordan Michael Smith notes the absence of the realists in the GOP:

"Even as recently as the 1990s the Republican Party was hospitable to realism. The party was divided about sending troops to the Balkans and spurned the concept of nation-building. As a presidential nominee in 2000, George W. Bush emphasized humility as his overriding foreign-policy theme..."But 9/11 obliterated the realist presence in the GOP. Figures like Scowcroft and Powell were marginalized as Republicans jettisoned their humility and embraced nation-building."

For fear that this perception is an overblown reaction generated by an overactive conspiracy theorist, no less a neoconservative icon than William Kristol of The Weekly Standard recently boasted of the purging from the GOP of what he described as "old-fashioned Arabists." Of particular note was Kristol's re-telling of Pat Buchanan's exit from the party:

"I was very happy when Pat Buchanan was allowed - really encouraged I would say by George Bush and others . . . in 1998 and 1999 to go off and run as a third party candidate."

Although this wouldn't be the first time Irving Kristol's son was wrong, Buchanan collaborator Scott McConnell refutes this fable:

"A New York Times story from 1999 cites the numerous efforts GOP luminaries were making to keep Buchanan from bolting the party. . . ."The article went on to say Bush had talked to Buchanan on the phone, and sent emissaries to persuade him, though it was to no avail."

The effects of the endorsements of Scowcroft, Kissinger, and Powell are actually overemphasized. Scowcroft and Kissinger at least, are names today usually only found in chapters of late Cold War textbooks. But their concerns reflect the domination the neoconservatives have held on the party's foreign policy to the detriment of differing views.

Whatever one might interpret from these events, the results are still the same. Buchanan was gone, there was no intra-party dissent in the march to Baghdad, and the party suffered electoral ruin. Kristol may boast that Ron Paul floundered in the primary but the fate that has befallen the Republicans is partly the result of a narrowed spectrum of opinion that Paul has assisted in correcting.

Today Mitt Romney, a man whose foreign policy pronouncements-- like the one about Russia-- are prima facie evidence of his inexperience, has used his reckless statements to appeal to the elements of the party he believes still hold the most sway. But in doing so he is also working with a coterie that is actively shrinking his party.