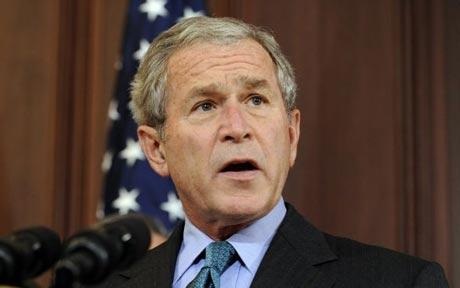

George W. Bush Returns to Polish His Legacy, Discuss Foreign Policy

Of the greatest verities of American politics is former president George W. Bush's gift for obliviousness.

In a speech given at the recently-unveiled Bush Institute at Southern Methodist University and adapted into a Wall Street Journal editorial on Friday, the former president affirmed several hallmarks of his administration's foreign policy: an intention to support "the people" against oppressive governments, treatment of women in foreign countries, and a rhetorical slap at anyone opposing his policy of intervention: "The idea that Arab people are somehow content with oppression has been discredited forever."

Bush's address and editorial is somewhat of a surprise. During the Republican presidential primary process the forty-third president was probably the only significant GOP figure to receive less direct attention than Ron Paul. The absence of Bush has been noticeable though it is hardly a mystery: Bush's name is still a pox on the American body politic.

While Bush's approval numbers may be rising now that he is out of office, there is no denying they were historically low when he left. The reason, of course, was that by the end of his second term, Bush had proven so incompetent as a president through the busted housing bubble, tanking economy, and failures of Iraq that no one, especially no one in his own party wanted to be associated with him.

Although prominent neoconservatives like Elliott Abrams have tried to attribute the Arab Spring to their policies, Bush was careful not to do so. He did, however, juxtapose many of his own interpretations of the Arab Spring with much of his foreign policy rhetoric, perhaps slyly trying to plant the idea in the minds of many that his unpopular foreign policy had something to do with the rebellions in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Syria.

Is there any reason, however, to believe that Bush's foreign policy had anything to do with populations rising up against oppressive leaders when it was Bush himself who coddled Mubarak in Egypt and welcomed Qaddafi in from the cold? But rather than accepting any responsibility for the failures, particularly in Iraq, which his policies instigated, Bush is hoping to repackage his accomplishments for posterity and above all, hoping that future generations will forget what he actually did while in office.

It's an encouraging sign that the Republican Party is actively trying to avoid its last president, suggesting that even they know the Bush legacy, three years out of office, is toxic. What is not assuring, however, is that there has been no meaningful repudiation of either him or his policies. Such behavior implies that Republicans are more concerned with the perception of Bush and his legacy, less concerned with whether those policies were destructive to the nation or its constitution, and likely believe that Bush's agenda was fine though it might have been imperfectly executed.

Therefore, the fact that Bush is re-surfacing in speeches, editorials, and endorsements and that his approval is rising post-presidency is bad news for the real conservatives in the party and should not be welcomed. While it may be satisfying for his remaining supporters, they might also need to be reminded that if Bush's reputation is rehabilitated it may be because historians are notorious for rewarding presidents who extra-constitutionally expanded their power and suppressed liberties.

While it may be true in love that absence makes the heart grow fonder, failure to remember why the party suffered brand-tarnishing makes it easier for it to happen again.